Urban Studies 200 & Geography 250

Welcome to the City!

Cities represent the very best and the worst of the human condition. E. Barbara Phillips, one of the most insightful urbanists of our time, opens her important book City Lights with an imaginative suggestion:

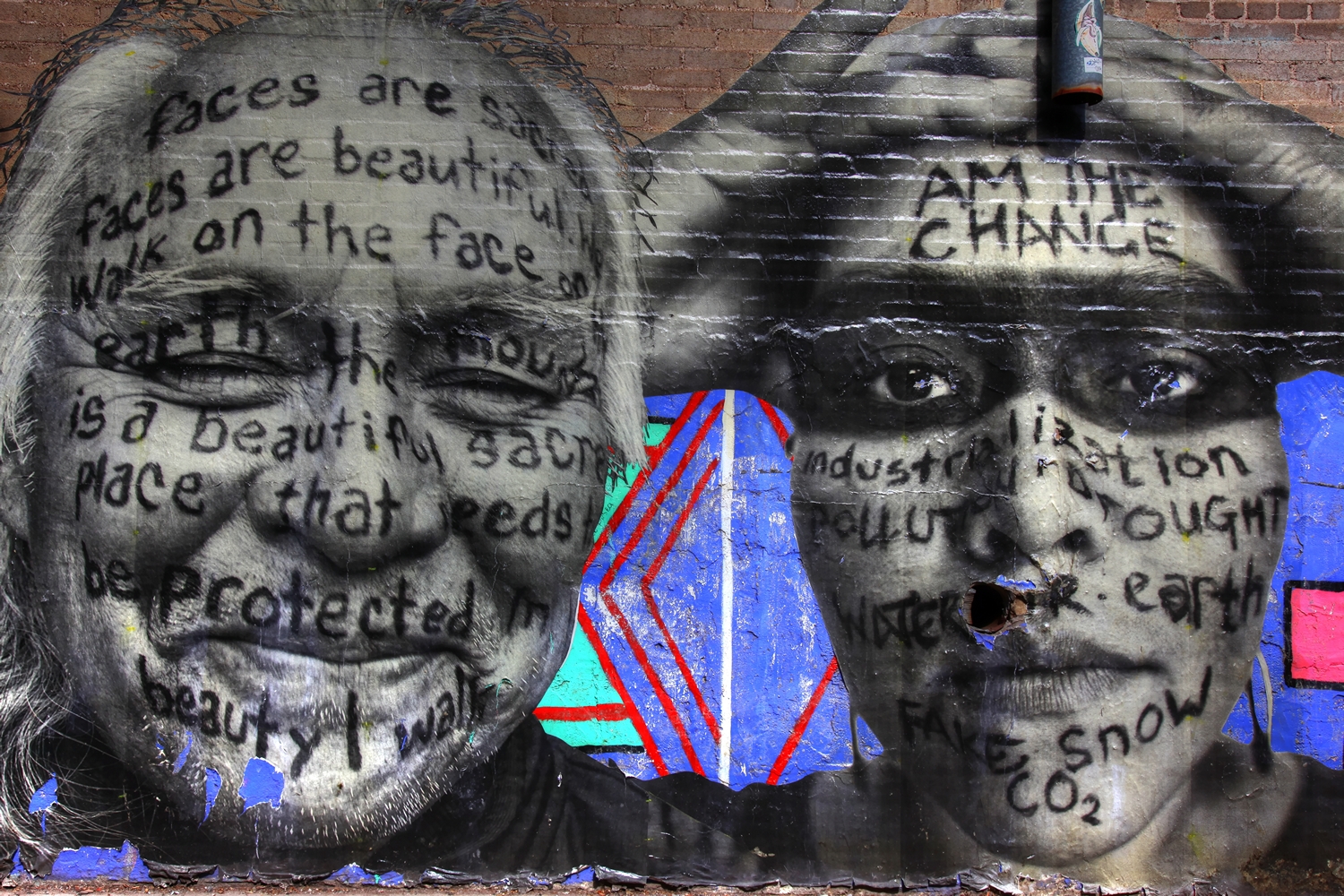

"If you close your eyes and think about the city, what do you visualize? Sleek skyscrapers? Great libraries and good food? New ideas and world-changing inventions? Walt Whitman's Brooklyn Bridge and Gustav Eiffel's tower? Rappers rhyming? Fans cheering for the home team? Trendy fashions and diverse pleasures? Or do you envision a bomb blast in Oklahoma City and a poison-gas attack in Tokyo? Short-tempered drivers honking in gridlock? People lining up at the soup kitchen? Heatless rooms with rats and roaches? Smells of Lysol and body sweat at homeless shelters? High schoolers hiding guns in the hallways? Chilling crimes and petty irritations? People sleeping, perhaps dying, on the snowy streets of Stockholm and St. Paul? Children living in tenements and tracts, dumpsters and vans? Or estates with signs threatening 'Armed Response'?

Perhaps your vision encompasses both urban glories and dilemmas." (Phillips, 1996, pp. 3-4).

Phillips' writing hits you right in the face with all the good, bad, and ugly, doesn't it? Personally, I'm an optimist -- and so I hope you think of the urban glories, all the joys, excitements, and energies of the city, and that the negative images recede into the background. What is clear, however, is that cities help to magnify, concentrate, and intensify whatever is happening in society.

Urban studies is the field devoted to understanding this process. It is interdisciplinary, which means that there are exciting discussions about cities among all sorts of people and scholars -- historians, sociologists, geographers, political scientists, anthropologists, economists, planners, architects ... the list goes on. Indeed, the range of people who study urban topics is so vast, and the words used by different experts are so varied, that it sometimes seems impossible to identify where urban studies begins and where it ends.

All definitions of academic subjects are, to some degree, artificial ways of simplifying the beautiful complexity of inquiry and learning. Everything is connected to everything else. But if we absolutely had to come up with a clear definition of urban studies, a way of putting "urban" into a separate box so we can take a focused look at it, what would it look like? Three definitions are most useful.

First, urban studies can easily be defined by its object of inquiry -- people, places, and processes found in cities. So our subject might be said to focus on what's happening in the four hundred cities in the world with populations of at least one million, or perhaps just the nineteen "city-regions" with more than ten million people. Yet other questions immediately appear: does urban studies include suburban areas, places where "anti-urban angst" often prevails? Does it consider rural areas that are deeply shaped by their interactions with big cities? (I respond to these questions with an enthusiastic 'yes,' but not everyone agrees.)

Second, the field can be defined by its approach. Urban studies is a vibrant and rich blend of theories and methods drawn from a variety of formal disciplines. But all of these theories and methods are bound together by the attempt to understand multi-faceted phenomena in and of the city. This means that urbanists approach their work by using whatever tools seem to work best for the specific question at hand. That sounds like a statement of the obvious, and indeed it is. But the subtle point is this: because cities are multi-faceted, complex, and defined by difference or even conflict, then the approach used by urban studies researchers necessarily has these features as well. Diversity, difference, and disagreement are built into the very identity of what it means to take an 'urban studies' approach to any specific topic or question. Beware of anyone who tells you that There is One Right Way to Study Cities.

Another complication is that the goal of understanding cannot be divorced from the desire for action, for progressive change to improve cities and urban life. Consider how Richard LeGates and Frederic Stout survey the field:

"'Urban Studies' is the term commonly used to refer to the academic study of cities. Knowledge about cities generated by social scientists and others is sometimes taught in a single program, sometimes dispersed among academic departments. The goal of these courses is primarily to teach students to understand cities, only secondarily to empower them to change cities. On the other hand, professional city planning, town planning, and regional planning courses explicitly train students to work as city planners. Often planning courses are taught as part of graduate or undergraduate professional degree programs; sometimes as part of geography, architecture, or departments in the social sciences. ... We feel planning and policy should be informed by understanding and that studying urban planning and policy can enhance understanding." (LeGates and Stout, 2003, pp. 2-3.)

A third way of answering this question is a bit more realistic, and perhaps more honest as well. Our field is defined in large part by the actual scholarly activities of its protagonists. And so things like circumstance, context, history, and personalities matter just as much as abstract principles, theories, and definitions. As one illustration, consider the circumstances around the birth of perhaps the most prominent journal in the field, Urban Affairs Review. The journal was established in 1965 by the co-founder and president of Sage Publications, "during days of urban unrest, protest over the Vietnam war, and a growing consensus that the condition of cities, in the United States and elsewhere, demanded concerted attention." Sara Miller McCune, the publisher, was concerned at the time "that publications in the social sciences did not actively reflect the urban world -- they didn't cross disciplinary lines to study what was fully happening in, say, cities." Miller McCune also launched a series of ambitious "Annual Reviews" that gradually became a "type of virtual community of interdisciplinary scholarly study directed at social critique and action" as well as a deep concern for the intricacies of public policy. (Marston and Perry, 1999, p. x, xi). More recently, however, the old associations of the word "urban" -- which stood in for the protests and social movements and inequalities that were of concern to people in the United States and Western Europe -- have been replaced by new sets of meanings. "Cities" now mean growth, modernization, development, competition -- the future of an inter-connected, fast-evolving planetary capitalism. A generation ago, "Urban Studies" was often seen as a mildly interesting sideline, something marginal and not fundamental. Now the urban is where it's at. A growing number of the world's leading thinkers are focusing on cities. Richard Florida has built a lucrative career analyzing (and encouraging) the way cities compete with one another to attract hyper-innovative young professionals in the "creative class" (he recently spoke at an event in Vancouver with Ray Kurzweil -- see this). The economist Edward Glaeser has declared that the city is humanity's greatest achievement; the city "makes us richer, smarter, greener, healthier, and happier," and it makes us "an urban species" (Glaeser, 2011, p. 7). Glaeser has become a wildly popular expert on cities, and travels around the world to advise key thinkers and policy elites on the consequences and opportunities of an urbanizing world. But other prominent urbanists look beyond the urban elites, and focus on the mobilization of crowds of urbanites in the streets of cities shaped by rising inequalities; the most influential is David Harvey (see Harvey's 2012 Rebel Cities). Not long ago, the differences in the urban perspectives of conservative urban economics and radical human geography were showcased nicely in a debate/conversation between Glaeser and David Harvey -- see this).

As noted above, however, all disciplinary boundaries and definitions are somewhat artificial. My own bias is to approach urban studies less as an "object" and more as a lens -- a way of seeing the world from an 'urban' perspective. I have little doubt that this perspective will become more widespread and more important: a few years ago, global population estimates suggested that for the first time in human history, an outright majority of the world's people lived in urban areas. For the forseeable future, nearly all of the world's projected population growth will take place in urban areas. In many ways, therefore, the general questions and challenges for human civiliization are becoming distinctively urban questions and challenges. So we have a lot of fascinating and important things to explore...!

References

Glaeser, Edward (2011). The Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier. New York: Penguin.

Harvey, David (2012). Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso.

LeGates, Richard T., and Frederic Stout (2003). "Introduction." In LeGates and Stout, editors, The City Reader, Third Edition. New York: Routlege, 1-5.

Marston, Sallie A., and David C. Perry (1999), "From the Series Editors," in Robert A. Beauregard and Sophie Body-Gendrot, editors, The Urban Moment: Cosmopolitan Essays on the Late-Twentieth Century City. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, ix-xii.

Phillips, E. Barbara (1996). City Lights: Urban-Suburban Life in the Global Society, Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

*

.

Above: Downtown Vancouver, June 2008; Below: Abandoned Packard Plant, Detroit, Michigan, July 2010 (Elvin Wyly).

CopyLeft 2019 Elvin K. Wyly

Except where otherwise noted, this site is

Davie Street, Vancouver, August 2012

Urban Studies Journals

Urban scholars publish in many different kinds of books and journals. Here are some of the best places to find the latest advances in our thinking about cities and urban life. Please note that you may need to be working on a computer at UBC, or through a Virtual Private Network, for these links to give you full access to the articles.

A few quotes about cities to get us thinking in an urban mood...

"Like every such golden age of which we know, it was an urban age."

Sir Peter Hall (1998). Cities in Civilization. New York: Pantheon, p. 3.

"This book opens with a city that was, symbolically, a world: it closes with a world that has become, in many practical aspects, a city." Lewis Mumford (1961), The City in History. New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World, p. xi.

"As we collectively produce our cities, so we collectively produce ourselves. Projects concerning what we want our cities to be are, therefore, projects concerning human possibilities, who we want, or, perhaps even more pertinently, who we do not want to become. Every single one of us has something to think, say, and do about that."

David Harvey (2000). Spaces of Hope. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 159.

"The destruction of the cities can be understood if put in old-fashioned cops-and-robbers terms -- there were a bunch of bad guys who stuck up the cities and rode away with the gold."

Brian H. Boyer (1973). Cities Destroyed for Cash. Chicago: Follett Publishing Company, p. 4.

"The world has been experiencing an unusually expansive and reconfigured form of urbanization that has defined a distinctively global urban age -- one in which we can speak of both the urbanization of the entire globe and the globalization of urbanism as a way of life."

Edward Soja and Migeul Kanai (2007). "The Urbanization of the World." In Ricky Burdett and Deyan Sudjic, eds. (2007). The Endless City: The Urban Age Project by the London School of Economics and Deutsche Bank's Alfred Herrhausen Society. London and New York: Phaidon Press, pp. 54-69, quote from p. 54.

"Cities in Russia today are the products of czarist, Soviet, and post-Soviet Russian societies, as well as of the many different ethnic groups and cultures that inhabited the region for at least a thousand years."

Beth A. Mitchneck and Ellen Hamilton (2003). "Cities of Russia." In Stanley D. Brunn, Jack F. Williams, and Donald J. Zeigler, eds., Cities of the World, Third Edition. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 223-253, quote from p. 250.

"A city needs to be reinvented, again and again, from the evolving shared consciousness of its people. ... Today, more and more people are becoming aware of this and are taking part in a movement to save a few remaining relics of Hong Kong's past -- an old street here, a clock tower or police station there. They may fail, of course, but in making the effort they help to keep alive a collective memory which, however fragile, will shape Hong Kong's destiny."

Leo Ou-fan Lee (2008). City Between Worlds: My Hong Kong. Cambridge: Harvard/Belknap Press, p. 280.

"I know this place like the back of my heart."

Quotation from an anonymous resident of Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, which introduces Wendy Pedersen and Jean Swanson (2010). Community Vision for Change in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Vancouver: Carnegie Community Action Project.

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Abandoned Packard Plant, Detroit, Michigan

Summer 2024, getting ready for September...!

Hello! Welcome to an urban world, and welcome to "Cities," Urst 200 / Geog 250!

You and I are part of the first generation ever to have lived in a majority-urban world: the globe crossed the fifty-percent threshold only a few years ago. While individual cities can be traced back hundreds and in some cases thousands of years, at the global scale an urban world is something entirely new. It means that all the wonderful, exciting things about the world -- as well as its horrible dangers and catastrophes -- are becoming inherently urban phenomena. Understanding cities is more and more important, across many fields of academic study as well as the challenges and opportunities of everyday life.

Here's a copy of syllabus for a recent offering of this course. Don't be intimidated when you open the document -- this is a rather easy course, and the syllabus is so long just because there are so many exciting stories to tell, and we want to make sure you get your money's worth! Note that this is a syllabus for a previous year -- so all the dates will be updated, and there will be a few changes in topics and recommended readings.

We'll be using several texts for this course. It is not absolutely required, but I do strongly recommend that you get a copy of E. Barbara Phillips, City Lights: Urban-Suburban Life in the Global Society, Third Edition. It's a wonderful book, even if it is a few years old by now. I don't know how much the UBC Bookstore will charge you, but used copies are currently selling on Amazon for about US$60. We'll be using a few other reading resources, but these will be freely available in digital form from UBC Libraries.

The second thing you should do is to mark out this date on your calendar: Saturday, September 7, 2024, 9:00 AM. Every year we do a walking tour around parts of the City of Vancouver, exploring a few of the places and processes that make this one of the most fascinating expressions of urbanism in the world. (This is a class about cities, not only Vancouver, but many of our stories begin here or have some sort of Vancouver connection.) We meet at 9:00 AM at the intersection of Granville and Georgia, and we walk around for ... well, a long, long time. But you can join us late, and you can leave us early. If you do stay with us till the very end I'll buy you food and drink in this part of the city.

If you're interested in what students have said about this course in previous years, here's a big collection of the formal evaluations from the last dozen years or so, in all their wondrous glory! Many students enjoy the course and find it useful; others, not so much. You'll notice that in the Covid era some students were not happy that the lectures were pre-recorded, and there was not sufficient opportunity for "live," interactive conversations during the lecture time slots. Excellent point! Hopefully there will be no pandemic public health restrictions this year, so we'll have plenty of time for conversation during the lecture time slots. You also have many other opportunities for interactive conversation. You'll be meeting weekly in the discussion sections with our Graduate Teaching Assistants, who are in any event much more brilliant than your instructor. You should also join us for conversations during the September walking tour. And please come to office hours for long conversations about anything and everything related to cities and urban life! I'm happy to give you lots of live, interactive lectures and conversations if you stop by office hours; ask me a few questions and pretty soon you'll be looking for the off switch on my face! For the scheduled class time slots in Geography Room 100, lectures are revised every year, but must be recorded in order to a) edit all the necessary concepts, illustrations, video narratives, and other required materials to fit within the time constraints of the scheduled class period, and b) ensure all students have consistent, equitable access to identical course materials. UBC, moreover, is becoming more and more like Vancouver's "Hollywood North" industrial composition -- which means that there's lots of rules and regulations. In recent years, when classroom discussions have been livestreamed or recorded, UBC attorneys have in some cases required that for everyone visible or audible in the scene -- including students who ask questions -- there must be a signed legal consent form, or that a legal warning be posted outside the lecture hall. (You'll see these kinds of notices quite frequently around the UBC campus whenever a film crew is working on a movie or commercial, often warning you not to take photographs, like this. I carefully pointed the lens away from the production sets, actors, and sets.)

Materials farther down on this page are from the old, pre-Covid era when this primitive web site was used for the course. Now we do the course in various hybrid forms depending on the latest public health guidelines; we'll have a blend of face-to-face conversations, recorded lectures, and online choices through UBC's LMS ('Learning Management System'), which is called Canvas.

September, October, and November 2021 were unusually challenging and confusing for many students and instructors at UBC (and many other universities too!). Every week we were bombarded with emails from administrators with new (and often contradictory) instructions. We were told that we were required to provide in-person instruction. But other requirements specified provisions to accommodate a significant number of students who were unable to be in person due to travel restrictions and other circumstances. We all hope that September, 2024 will be fully free of such complications Covid or other pandemic conditions!

Join us to learn some of the fascinating stories of the remarkable transformations of a world of planetary urbanization!

See you in September!

*

"I’ve spoken for more than long enough. But someone will expect a ringing conclusion. I’m not sure I have one. If I do, it reads something like this. First, above all, planners should understand history and the importance of the historical moment. They should seize the hour and the day: there are moments, a very few moments, that actually matter in the history of cities as of everything else, and the critical point is to be there, and to act. Second, there are certain values that are inseparable from being a planner, rather like a doctor’s Hippocratic oath. You cannot just be opportunistic; you have to define what it is that you want to achieve, even if you have to modify and temper those objectives in the course of day-to-day practice. I once heard the great systems planner, C. West Churchman, give a seminar in Berkeley. It was a bit of a disaster because he refused to say anything, insisting that first the students had to ask questions and he’d answer those; and in the resulting silence, I recall, a large dog walked in and made off with his lunch in its teeth. But he did eventually say something that I thought odd at the time, and have been thinking about ever since: he said, 'If you’re going to be a planner, you’d better first work out your religious beliefs, because until you’ve done that you can’t even start.' I think that I now know what he meant, which was that you’d better get your value systems straight in your head." Peter Hall (1996). "It All Came Together in California: Values and Role Models in the Making of a Planner." City 1/2, 1-12, quote from pp. 11-12; reproduced in Paul Knox (2014). "Sir Peter Hall, 1932-2014: 'Seize the Hour and the Day.'" Urban Geography 35(8), 1107-1110, quote from p. 1107.

"When Anar Sabit was in her twenties and living in Vancouver, she liked to tell her friends that people could control their own destinies. Her experience, she was sure, was proof enough." But things would change in cities and nations that would eventually reshape Sabit's life in profound ways. At one point amidst an intensifying blend of ethnonationalist consciousness and cybernetic antiterrorist authoritarianism, "she began to feel a deep alienation. No matter where she went ... she remained an outsider. One day, back in Shanghai, she looked up at the city's towering apartment buildings and asked herself, 'What do they have to do with me?'" Raffi Khatchadourian (2021). "Ghost Walls." The New Yorker, April 12, 30-51, quotes from p. 30.