Better than Angie's List

If you're interested in recommendations on whether this walking tour is worth it, here's one of the more interesting reviews received.

It's a September morning in 2012. We're just about twenty minutes into the tour. We've walked down the hill from the intersection of Granville and Georgia, and now we're on Georgia Street right out in front of the Scotia Tower. Surrounded by a good crowd of curious, brilliant students, I'm telling a few stories about Vancouver's experience with the "urban renewal" movement that swept through so many cities in Europe, the United States, Canada and beyond in the 1950s through the 1970s. On this site a beautiful "terracotta-clad beauty" of a building constructed in 1913, the Birks Building, had been demolished in 1974 despite grassroots opposition - a loss that led the City of Vancouver to establish an architectural conservation program (Kalman and Ward, 2012, p. 125); an adjacent building, the Strand Theatre built in 1919, was also destroyed to make way for the new and the modern - the Scotia Tower, completed in 1977.

At this point a guy walks across the intersection, and pauses for twenty or thirty seconds to listen to the stories about urban renewal - an era of urban thought and planning practice that was once widely accepted as a logical, scientific technology of improvement. Urban renewal gets its own formal dictionary definitions - "The rehabilitation of those portions of urban areas deemed to have fallen below prevailing standards of public acceptability," in the words of one influential source (Hoare, 1988, p. 514) - but it also entails many serious problems. Urban renewal was driven by top-down decision-making, with little public input; it assumed that newer buildings were always better than older structures; and it often undermined existing communities while making cities more expensive and competitive.

Our visitor starts walking up Georgia Street, and then turns around. "Hey, I've been here all my life," he declares to the crowd in a loud, bold voice. "And I know this place!" He looks at me to make eye contact, and then he shouts, louder this time, with passion,

"...and I think you're full of shit!"

Then he stumbles just a bit, turns around, and resumes walking west up Georgia. It's no criticism to observe that he seemed to have a pretty nice mixture of something on board, and this metropolis is a particularly dynamic vortex of all sorts of natural and high-tech cognitive enhancements; the legendary urban researcher Loretta Lees (2001) once described the place as a "city on Prozac," and that was years before literally hundreds of cannabis retail stores proliferated as Canada's federal government prepared to de-criminalize the substance in 2017. It is therefore important that we respect our critic's wise assessment. In the moment, his admonition - "I know this place!" - reminded me of an anonymous resident's quote that introduced a report by a local community organization based in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside neighbourhood. "I know this place like the back of my heart," the resident had told the organizers and researchers (Pedersen and Swanson, 2010). The Downtown Eastside is famous across Canada and beyond as an epicenter of poverty and drug use - and yet such narratives are terribly unfair stereotypes that ignore the true complexities of community and shared local experience. Besides, if there were time, there are plenty of stories to be told about what happens behind closed doors in other neighbourhoods in this region - with their own shares of wild, drug-fuelled parties in multimillion-dollar suburban mansions or high-rise luxury condominium penthouses.

But of course there's never enough time. We're on Georgia Street and a crowd of students awaits a response.

"Yes, indeed, I am!" I replied.

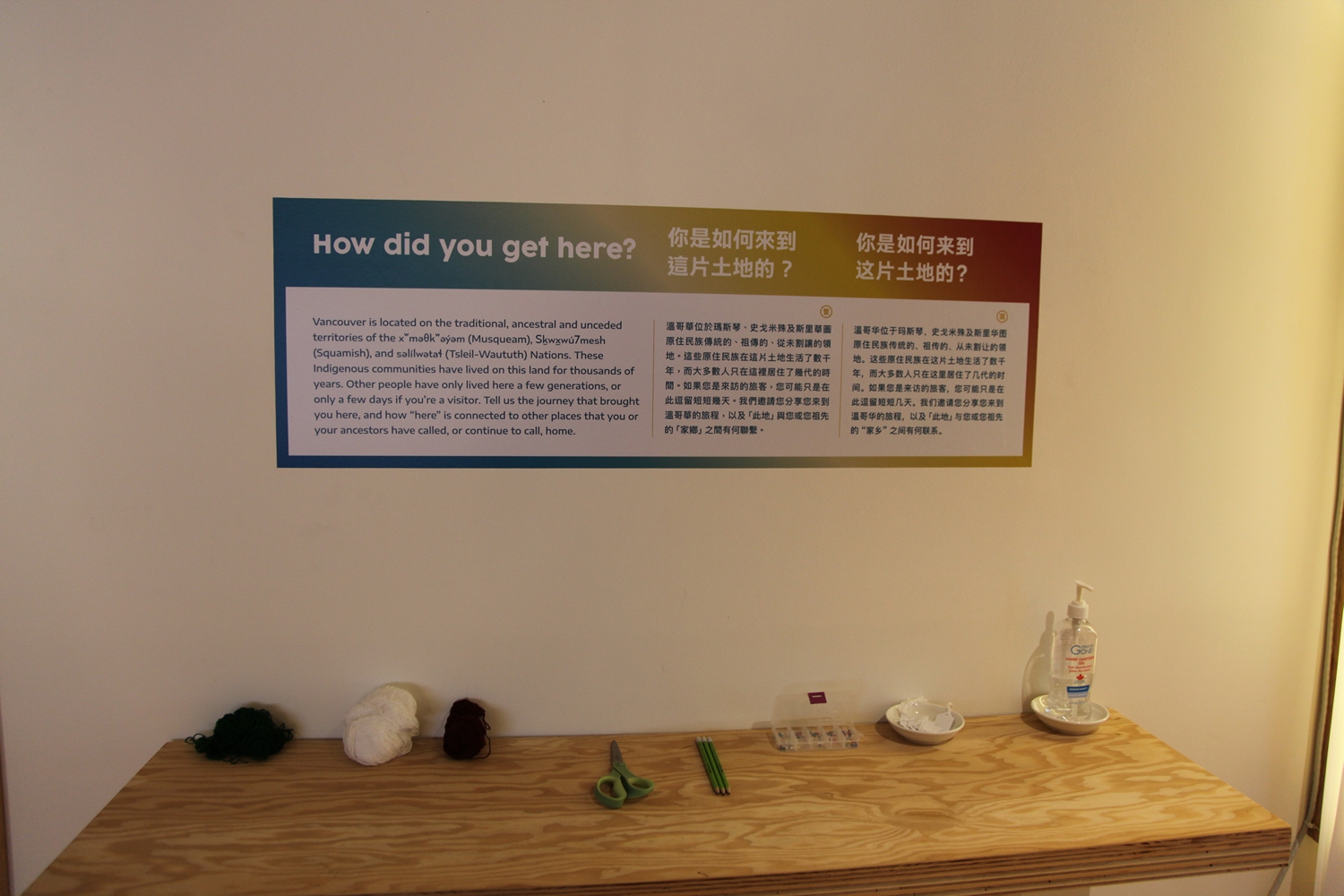

Our wise critic was walking steadily out of earshot by this point, but his review certainly provided valuable commentary - of the same sort found on the pre-Yelp ratings website Angie's List, where you can read and submit reviews of plumbers, gardeners, painters, and almost any other kind of person you can imagine hiring for home services. This was a valuable opportunity to explore the illusions of traditional understandings of knowledge and expertise produced over the course of the past few centuries. One influential philosopher warns of the "blind field" as we struggle to understand cities, because urbanism is a literal transformation of the experience of space and time, produced by the material and ideological distractions in the "accumulation of knowledge, technologies, things, people, wealth, money, and capital" (Lefebvre, 1970, p. 24). Cities are real, physical, material places, but they are also portals that allow and require that we perceive space and time in complex, non-linear ways. I spoke of the history of colonialism and dispossession upon which this city is built. Everything I do, think, and say in this region takes place on unceded Indigenous territory, which is another way of saying that the land has been stolen. Yes, I really am full of shit, from my very limited understanding of the full scope of Indigenous histories in this part of the world, to my increasingly frequent split-infintive grammatical lapses. ("A little Strunk and White is a dangerous thing," observes the publisher of the definitive Elements of Style [Plotnik, 1982, p. 3]; for a more humorous and enjoyable commentary on the strange rules of written communication in the English language, see Truss, 2004).

But self-awareness of ignorance is a very special kind of knowledge, and provides an invitation for learning and true insight. For those of us new to Canada and new to Vancouver, for example, we are likely to think of the City of Vancouver as located in British Columbia, a province of a nation-state with a large territory and a comparatively small population called Canada. That's certainly one way of thinking about it. Vancouver is routinely ranked near the top of rankings of the world's "most liveable cities," and Canada has the world's second-largest land area - 9.8 million square kilometers, second only to Russia's 17 million - with a population slightly less than that of the State of California's 39 million people. The images in our mind's eye might also include various symbols and slogans - snow, Polar bears, beavers, bilingual signs in English and French, hockey, Maple syrup or the Maple Leaf flag - as well as perceptions of how the place is very different from its neighbour to the south (including such curious subtleties as the extra u's in words like neighbour or colour).

All of these features and images do express certain real facets of this part of the world. But they're the beginning of the conversation, not the end. Recent Canada Day social media memes have included a reincarnation of the Maple Leaf flag in the Canadian Native Flag designed by Kwakwaka'wakw artist Curtis Wilson, and in Vancouver's temperate climate, sometimes you get lucky enough to watch a sunset from the beach at English bay before walking home to your West End apartment to watch the Stanley Cup finals in Hockey Night in Canada's Punjabi edition (see Ian Hanomansing's CBC story about Harnarayan Singh, who sometimes goes by the handle "IceSingh," here).

And as soon as you begin thinking about space and time in broader, open-ended ways, things get very, very complex. The City of Vancouver was formally incorporated in 1886, just a few human lifetimes ago. The entity today called Canada was created through a 'Confederation' of separate colonial provinces that began in 1867; even here, the process was and remains uneven and non-linear. Newfoundland didn't join Confederation until 1949. On April 1, 1999, after decades of organizing and legal struggle, a new flag and coat of arms were unveiled in the formal establishment of Nunavut, the homeland for the indigenous Inuit people in Canada's far north; Nunavut is the world's largest land-claims settlement between a modern nation-state and Indigenous peoples. In a book analyzing the cultural and political histories of relations between European colonialism and the diverse Indigenous societies of this continent, the philosopher John Raulston Saul (2008, p. 3) writes, "We are a métis civilization. What we are today has been inspired as much by four centuries of life with the indigenous civilizations as by four centuries of immigration. Perhaps more. Today we are the outcome of that experience."

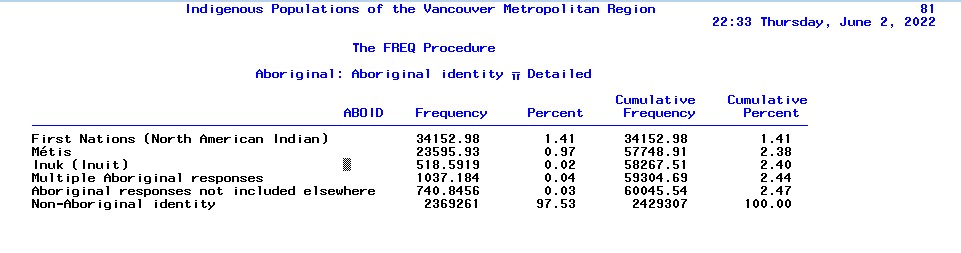

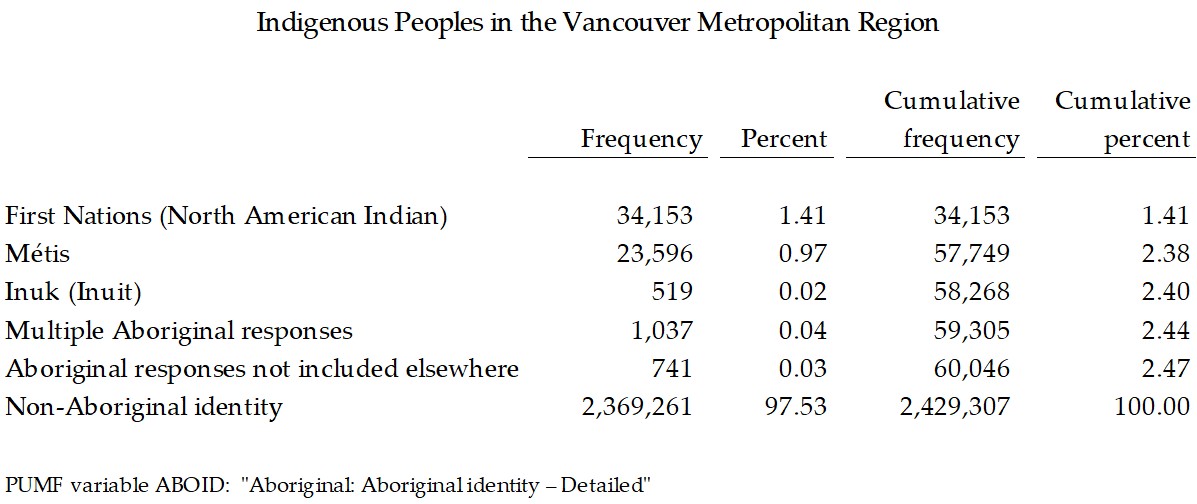

Saul's book is written for a particular audience - for upper-middle class and elite readers in the power centers of Ontario and Quebec who see themselves first and foremost as the descendants of the English and French. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these and other immigrants from Europe gradually moved away from identities as separate cultures (Irish, Jewish, Italian, Polish, German) and came be associated with a broader definition of 'whiteness' (see Roediger, 2018). Saul, therefore, is using the word "métis" in a general sense of cultural mixture, as well as a provocation. Saul's book is written to challenge the mindset of Canadian elites who remain obsessed with European and U.S. notions of power and prestige that all too often involve underlying assumptions of ethnic and racial purity. But 'Métis' has more specific, formal, and complex meanings in the histories and current commitments of organizations like the Red River Métis - La Nouvelle Nation, the Métis Nation British Columbia, and the North Fraser Métis Association. In Canada, the Métis peoples are descendants of early European fur traders and trappers, and Indigenous, First Nations peoples; early on, a pattern developed in which these 'mixed' peoples were marginalized both by Indigenous First Nations and colonial settlers increasingly influenced by the ideas of ethnoracial purity forged in the development of modern European nationalism. Even today you'll find difference and disagreement if you look for it. British Columbia - that phenomenon created in 1858 that we tend to think of as just a single provincial subdivision of Canada - is, in fact, comprised of hundreds of separate nations. One BC Government website lists 198 First Nations, while the BC Assembly of First Nations itself identifies 204 First Nations, with 34 distinct languages and almost three times that many unique local dialects. Not all First Nations agree on everything, and in some cases there are sensitive matters among BC First Nations and the Métis, most but not all of whom trace their ancestry to the Red River Settlement in present-day Manitoba, around what is today known as the City of Winnipeg. Some First Nations peoples who are indigenous to the lands now known as British Columbia see the Métis as uninvited settlers, not that much different from European colonizers. It is important to think carefully about such perspectives, while also noting that they reproduce some of the syndromes from previous centuries examined in Saul's (2008) history. Another option is to embrace difference while searching for agreement, learning, conversation, and the mutual challenges and opportunities of an interconnected world that has only recently become majority-urban. Not long ago, I spent time with several Métis elders in the Vancouver region, learning much from their wisdom. There was an Acadian Métis man who joked that in old photographs, all his ancestors looked Filipino; go back a few lifetimes here, and the Acadians in Nova Scotia were dismissed by the British as "a distinct race, a people by themselves," amidst years of tense negotiations between Britain and the rebellious new nation of the United States - with arbitration by King William I of the Netherlands - over the border between New Brunswick and Maine (see Meinig, 1993, pp. 124-125). That lineage also involves those who found Acadia more unfriendly with the border-drawing obsessions of nationalism, and departed for New Orleans, Louisana, in the late nineteenth century, where they came to be known as 'Cajuns.' Or consider the present and the future: on the medical frontiers of coping with the global Covid-19 pandemic is a bioscientist who recently earned a Ph.D. from the University of British Columbia, and who has now joined Oxford, working on the evolutionary genetic mutations of the coronavirus. She's the grand-daughter of a Métis elder, who proudly told me that she is "Asian-Métis."

Back in September of 2012 I knew some of these things, but I still had a lot to learn. Even today this complex urban region constantly teaches me new things and stretches the imagination; genuine immersion in city life is the true mind-altering psychedelic. "Vancouver, like the province in which it is located, is no easy place to understand," wrote a prominent environmental philosopher introducing an influential book on the changing physical and human worlds of B.C.'s Lower Mainland. Many "have despaired of grasping the essence of the contemporary city," Graeme Wynn (1992, p. xiii) explained; "'There is no real centre to Vancouver,' concluded one recent commentator ... it is a place of 'pockets, strips, [and] urban moments,' each of which is but a fragment of an intricate urban kaleidoscope. Because most people are familiar with only a few pieces of this fabric, most views of the city elevate one or two facets of its character above others." On the rest of our short itinerary around part of the urban core of Vancouver, I was able to remind myself of how little I know. We'd be standing in front of one building or another, and I wouldn't be able to recall if it has been completed in 1910, 1911, or 1912. Certain moments in the evolution of this city have involved wild orgies of construction, and various structures briefly held designations of 'the tallest building in the British Empire.' As I fumbled remembering the specific years of construction on the Dominion Building, or the Sun Tower, I'd remind everyone, "Well, we have it on good authority that I'm full of shit!"

Back in 2012, our tours of the "intricate urban kaleidoscope" were comparatively short. Walking and conversation around parts of the downtown core, Gastown, the Downtown Eastside, Chinatown, Hogan's Alley, and the Olympic Village would suddenly end after about four hours, and I'd think, "Oh, there's more stories to tell!" How did I forget to tell the story about Tommy Chong meeting Cheech Marin in Vancouver? Their comedy routine lampooning the drug busts of "Sgt. Stadanko" was based on a real police officer who worked undercover in Vancouver! (Mackie, 2017). Cheech and Chong's bit about Stadanko encouraging kids to turn in their friends and family or anyone who might be a "drug pusher" should make us think about Steppenwolf's famous song, which someone has remixed with lots of local images in a "420 Vancouver Edit." Tommy Chong's career also helped inspire the Vancouver comedian Charles Demers, who wrote a great book on the city published shortly before Vancouver hosted athletes and visitors from around the world in the 2010 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games (Demers, 2010). Most of the images seem to be from an actual 420 Day event on English Bay in the West End, which would in turn require explaining what 420 has often meant in police officers' radio dispatch codes. Vancouver has always been a major center of film production and other creative enterprises - a few years we watched as they closed down the Georgia Street Viaduct to film the opening scene of the bizarre film Deadpool; did you know that Ryan Reynolds is from Kitsilano? Still, Vancouver's nickname - "Hollywood North" - means that when someone gets just a little bit of success, they head off to the even bigger center of celebrity image and creativity, Los Angeles. Cheech and Chong headed for L.A. and became famous in comedy and films in the 1970s and 1980s, and the talent pipeline continues, as in the case of the Vancouver Film School graduate Leenda Dong - who did wild stuff in Vancouver and then partnered with the Fung Brothers in sendups like 'Asian Canadians vs. Asian Americans.' Think of Leenda D's praise for Drake as the "Prince of Canada" the next time you step into October's Very Own Store on Robson Street. Robson is Vancouver's version of the upscale retail streets like Chicago's "Magnificent Mile," or Hollywood's Rodeo Drive. Comedy, like cinema, can be a serious business, and when Leenda D and the Fung Brothers point out that America has fought so many wars in Asia, it's worth remembering how Bruce Springsteen wrote about soldiers coming home from Vietnam only to wind up unemployed as factories shut down and jobs disappeared; Springsteen's song was widely misunderstood - it's a critique of war-making mindless patriotism and nationalism, not a celebration - but Cheech and Chong got the right idea when they did a parody for undocumented Mexican-Americans, in "Born in East L.A." Not long after Springsteen performed at Rogers Arena in Vancouver surrounded by all the team logos for the local hockey team - "What the Fuck is a Canuck?" he asked the crowd - Sarfraz Manzoor's memoir, Greetings from Bury Park about growing up in Luton not far from London, was produced into the film Blinded by the Light ...

... oh, my, where did that stream of consciousness come from? Spend a little bit of time in YouTube or any of dozens of other portals into what the computer scientist David Gelertner calls "Mirror Worlds" and you see the real, material experience of urban life coalescing with the virtualities and connectivities of digitization, computation, simulation, and image. Have I told you about William Gibson and Neuromancer...?

... I could go on, and if you join us on the tour, we'll see how much energy we have. You can join us late, or you can leave early, and the entire tour is entirely optional. But I hope you can join us. This is such a fascinating urban region, a true portal into entirely different experiences of space and time.

References

Demers, Charles (2009). Vancouver Special. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press.

Hoare, Anthony G. (1988). "Urban Renewal." In R.J. Johnston, Derek Gregory, and David H. Smith, eds., The Dictionary of Human Geography, Second Edition. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 514-515.

Kalman, Harold, and Robin Ward (2012). Exploring Vancouver: The Architectural Guide. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre.

Lees, Loretta (2001). "Towards a Critical Geography of Architecture: The Case of an Ersatz Coliseum." Ecumene 8(1), 51-86.

Lefebvre, Henri (1970). The Urban Revolution. Translated by Robert Bononno, 2003 edition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Mackie, John (2017). "Hippie Nemesis Abe Snidanko Dies at Age 79." Vancouver Sun, August 9.

Meinig, D.W. (1993). The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Pedersen, Wendy, and Jean Swanson (2010). Community Vision for Change in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Vancouver: Carnegie Community Action Project.

Plotnik, Arthur (1982). The Elements of Editing. New York: Collier Books.

Roediger, David R. (2018). Working Towards Whiteness: How America's Immigrants Became White, Updated Edition. New York: Basic Books.

Saul, John Ralston (2008). A Fair Country: Telling Truths About Canada. Toronto: Viking Canada.

Truss, Lynne (2004). Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation. New York: Gotham Books.

Wynn, Graeme (1992). "Introduction," in Graeme Wynn and Timothy Oke, eds., Vancouver and its Region. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, i-xvii.