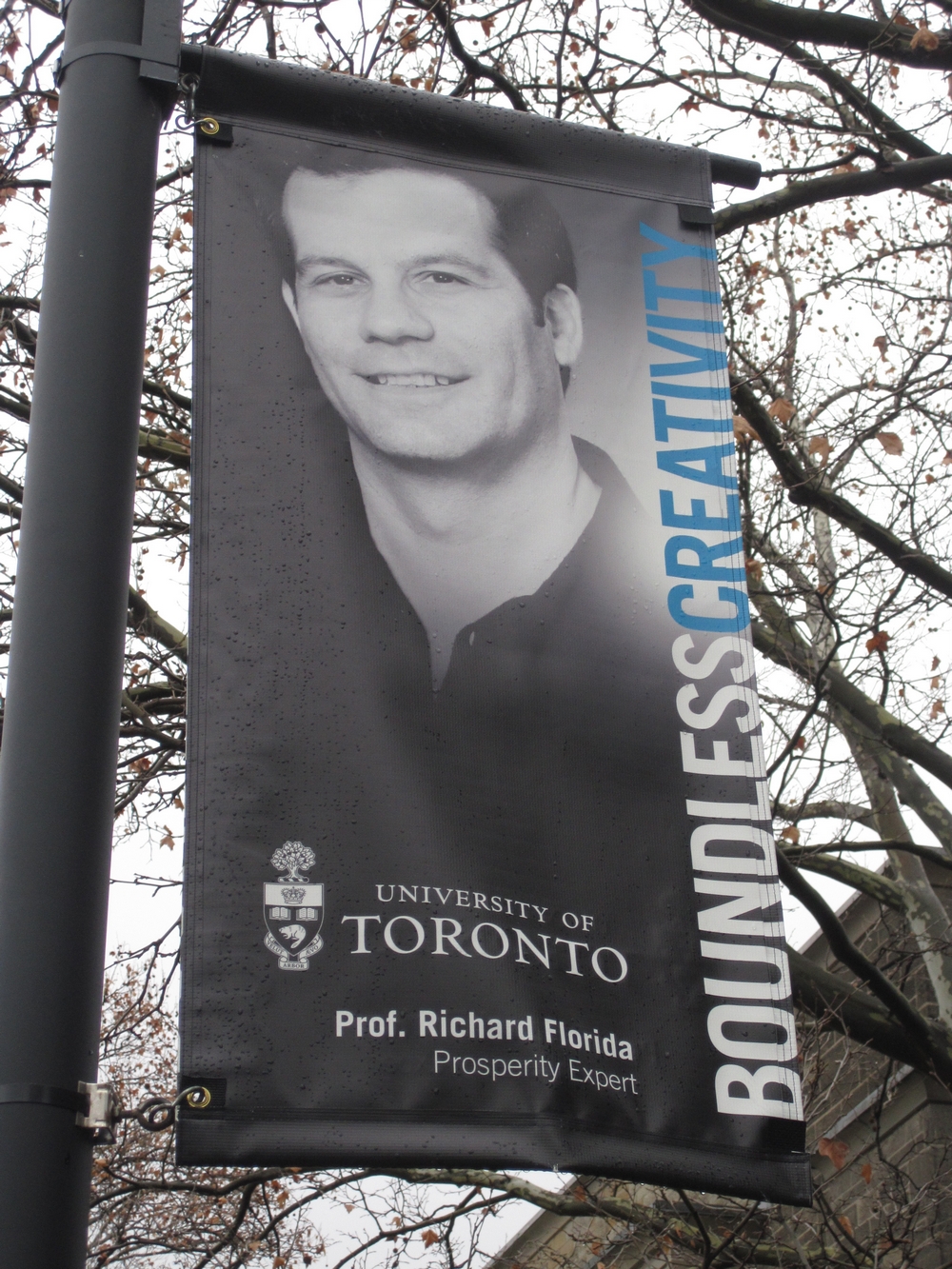

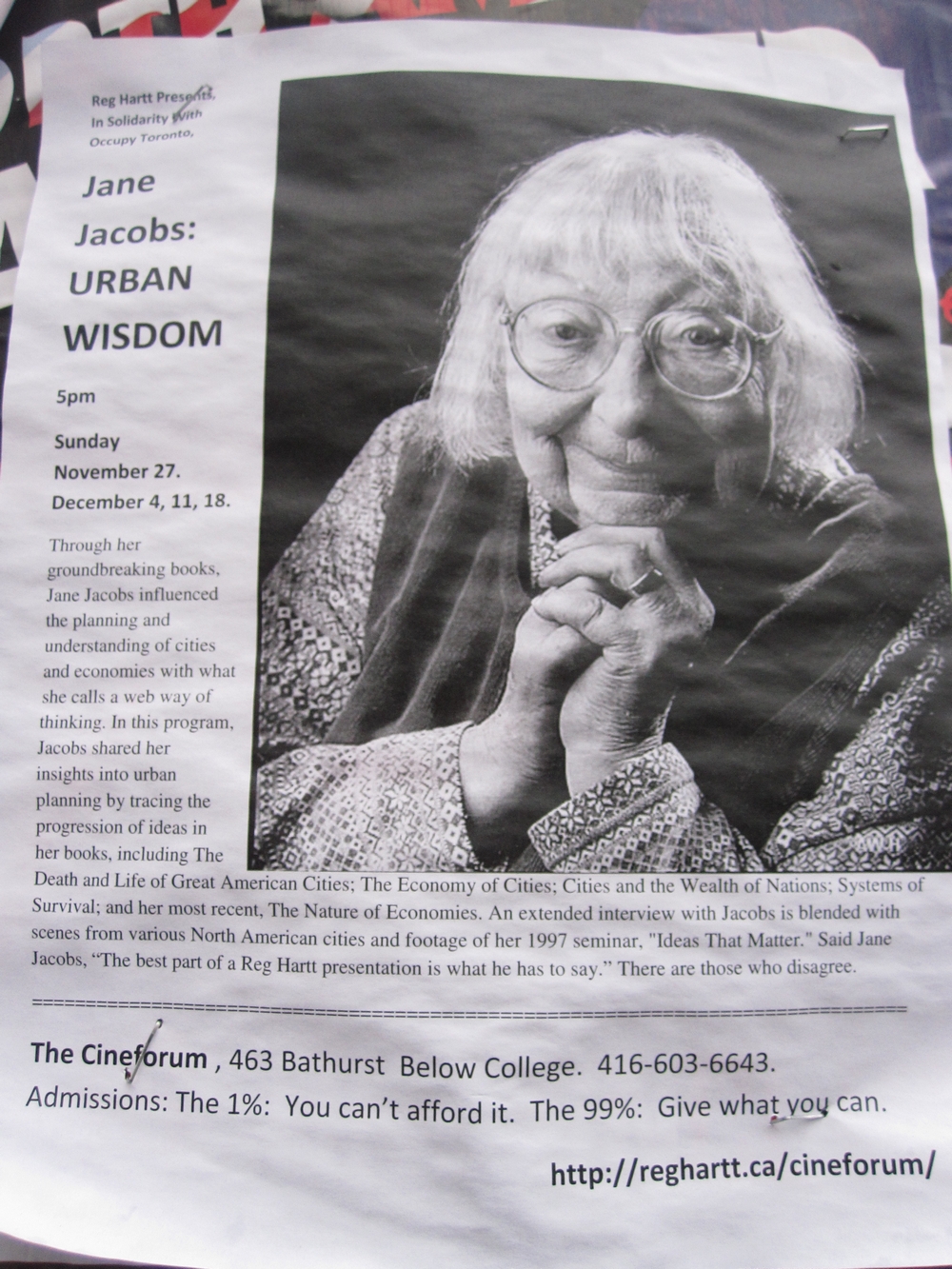

Photograph by Liam McGuire

"Depending on how it is defined, the greater Toronto region is the fifth or sixth largest metropolitan economy in North America and one of the continent's fastest growing mega-regions. The sustainability of [this growth], however, has been increasingly challenged by a range of economic factors and social changes, all deepened by the latest economic recession and global financial crisis."

Larry S. Bourne, John N.H. Britton, and Deborah Leslie (2011). "The Greater Toronto Region: The Challenges of Economic Restructuring, Social Diversity, and Globalization." In Larry S. Bourne, Tom Hutton, Richard G. Shearmur, and Jim Simmons, eds. Canadian Urban Regions: Trajectories of Growth and Change. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 236-268, quote from p. 236.

CopyLeft 2012 Elvin K. Wyly

Except where otherwise noted, this site is

Photograph by Liam McGuire

Mapping the Megacity: Growing Patterns of Socio-economic Polarization in the Ten Cities of Toronto

Liam McGuire

January 2012

Recently, urban scholars have drawn attention to a number of changes in the vast, sprawling cities that we call home. Primarily, Canadian cities are becoming more divided: neighbourhoods become either wealthy or poor places, as the middle class slips closer to oblivion. Cities such as Toronto are increasingly defined by a tale of two cities. City 1 is comprised of neighbourhoods of increasing wealth, while City 3 is made up of communities with a declining average income. In the midst of this geography of urban polarization is City 2, neighbourhoods that have retained stable income levels (Hulchanski, 2010). This "city" is quickly being swallowed up by a city landscape that has been made unequal by a changing global economy and urban policies that advance a neoliberal governance agenda. For David Hulchanski's 2010 report on the Three Cities of Toronto, see:

Hulchanski, David (2010). The Three Cities of Toronto. Toronto: Cities Centre, University of Toronto.

[Please follow the link; copyright laws prevent including the image here]

Within the context of a city region becoming increasingly polarized, this research specifically quantifies an emerging phenomenon, the suburbanization of immigration. Since the conclusion of World War II, immigration patterns in the General Toronto Area (GTA) have changed dramatically. The old pattern of first generation Canadians settling in the core and gradually moving outwards from downtown enclaves such as Greektown and Little Italy has evolved. In the present day, immigrants are largely settling in the suburbs, a vast landscape of sprawl stretching out from the downtown core in all directions (Murdie, 2008).

Murdie, Robert (2008). Diversity and Concentration i in Canadian Immigration. Research Bulletin 42. Toronto: Cities Centre, University of Toronto.

This pattern however, is far from homogenous. Immigrants in the suburbs are segmented vastly by income, some becoming homeowners in brand new communities, others renting overcrowded apartment buildings (United Way, 2011). In short, the urban region of Toronto is becoming increasingly unequal, putting households (especially first generation Canadians) as a high risk of homelessness (Preston et al, 2009). To really understand the geography of immigration in the current-day GTA, a two-step methodology is used, creating the classification of the ten cities of Toronto.

Building off of the tradition of factorial ecology, six dimensions have been constructed. Each dimension has been taken from a literature review on the challenges facing the contemporary Toronto CMA, covering six unique angles of urban analysis:

1 - Housing: Housing Tenure

2 - Housing: Physical Structure

3 - Citizenship

4 - Income

5 - Labour

6 - The Household Economy (Unpaid home labour)

Three factors were taken from each of these dimensions, creating a total of 18 maps, each exploring a different pattern across the Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) of Toronto. The Toronto CMA is the Toronto region, according to boundaries set out by Statistics Canada. You can view the collection of maps here.

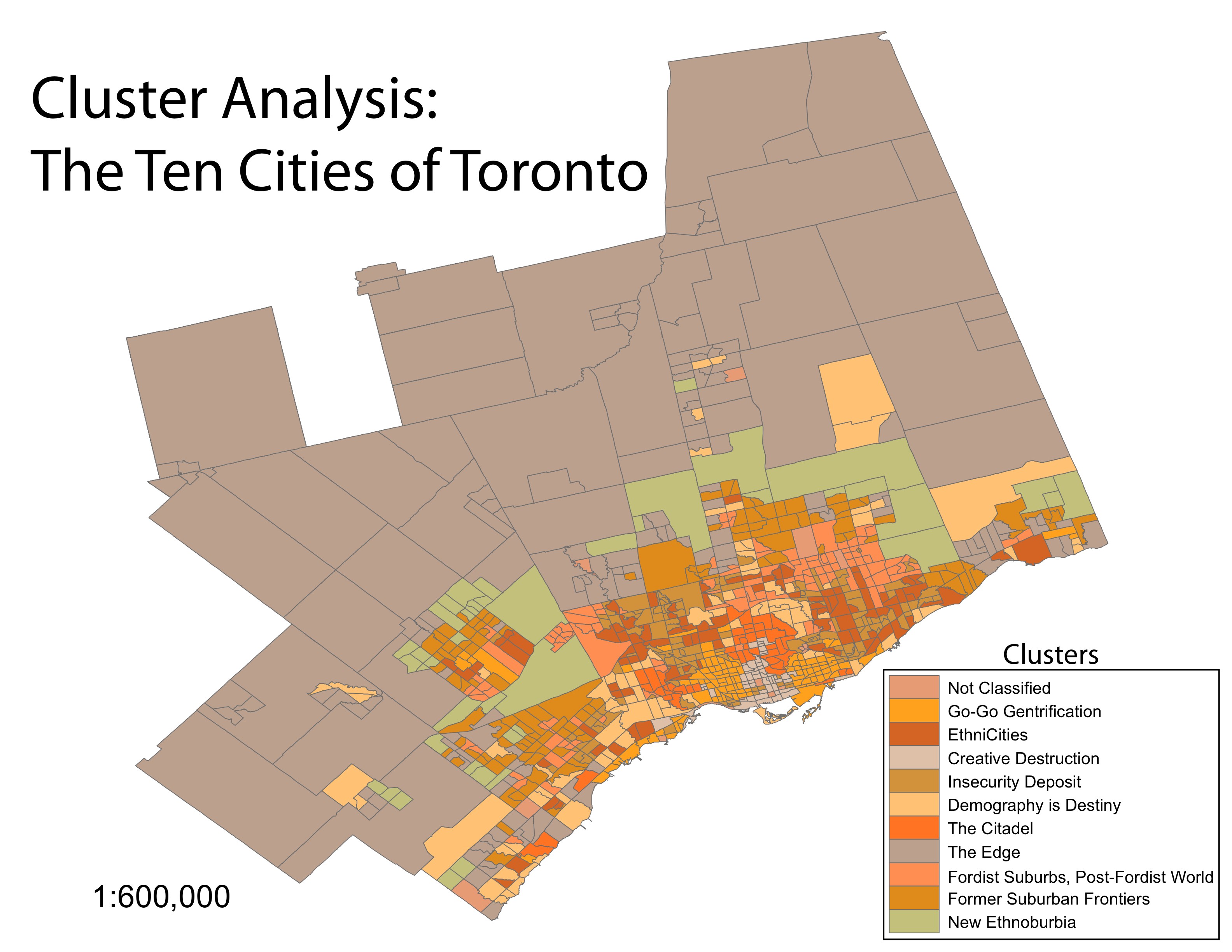

The second step in the research methodology was to perform a cluster analysis. The 18 factors collected in the earlier step have been arranged into ten clusters. Each cluster is a unique combination of the six dimensions. When mapped, this produces a visualization of the ten cities of Toronto: ten unique areas that show the segmentation of immigration patterns across the Toronto CMA, in addition to many other patterns of urban phenomena.

Recommended Sources

Cowen, D. and Parlette, V. (2011). Toronto's Inner Suburbs: Investing in Social Infrastructure in Scarborough. Scarborough: University of Toronto.

Harvey, D. (2008). "The Right to the City." New Left Review, 53: 23-40.

Keil, R. and Young, D. (2011). "In-Between Canada: The Emergence of the New Urban Middle." In D. Young, P.B. Wood and R. Keil (eds.) In-Between Infrastructure: Urban Connectivity in an Age of Vulnerability. Praxis (e)Press.

Peck, J. (2011). "Neoliberal Suburbanism: Frontier Space." Urban Geography, 32(6): 884-919.

Walks, R. Alan. (2001). "The Social Ecology of the Post-Fordist/Global City? Economic Restructuring and Socio-spatial Polarization in the Toronto Urban Region." Urban Studies 38(3), 407-447.

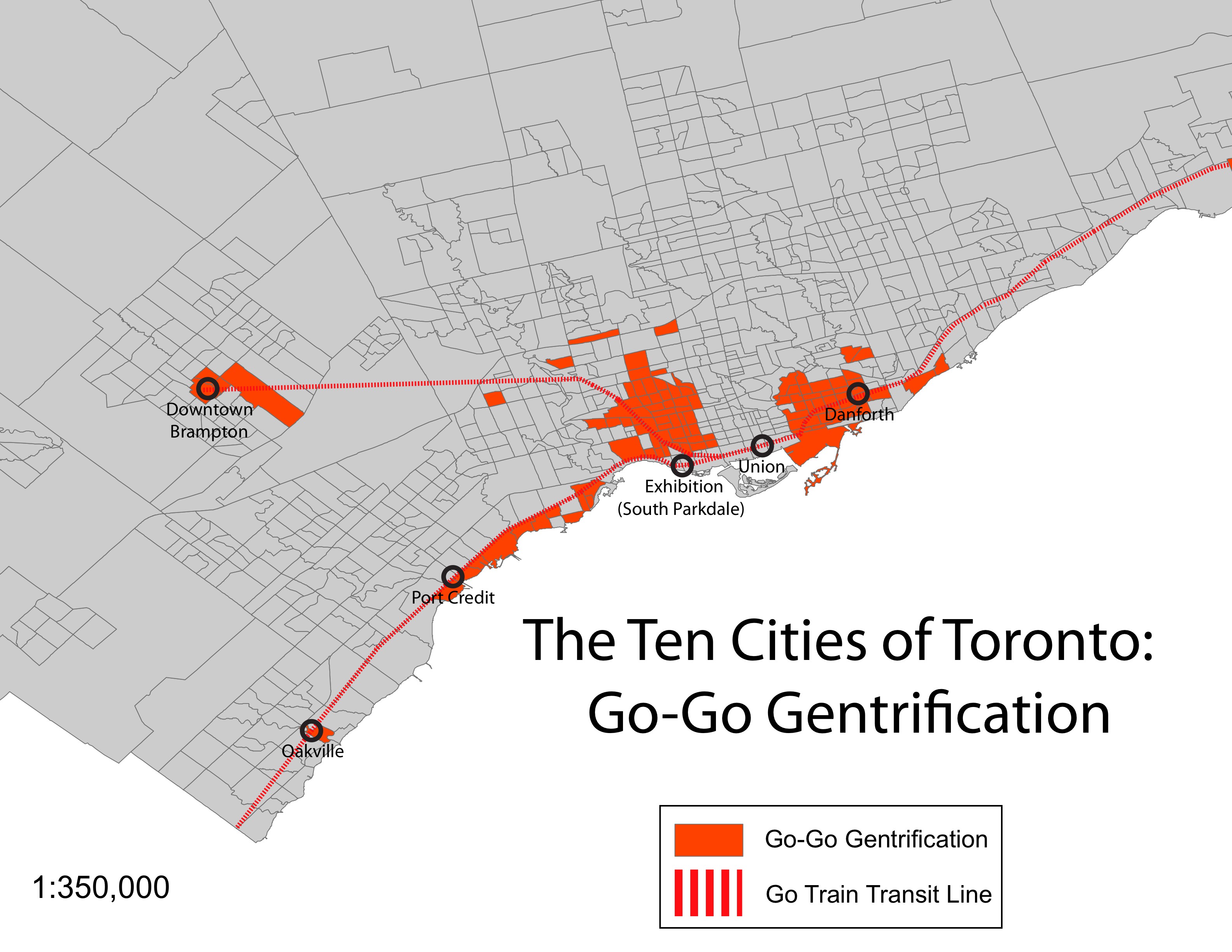

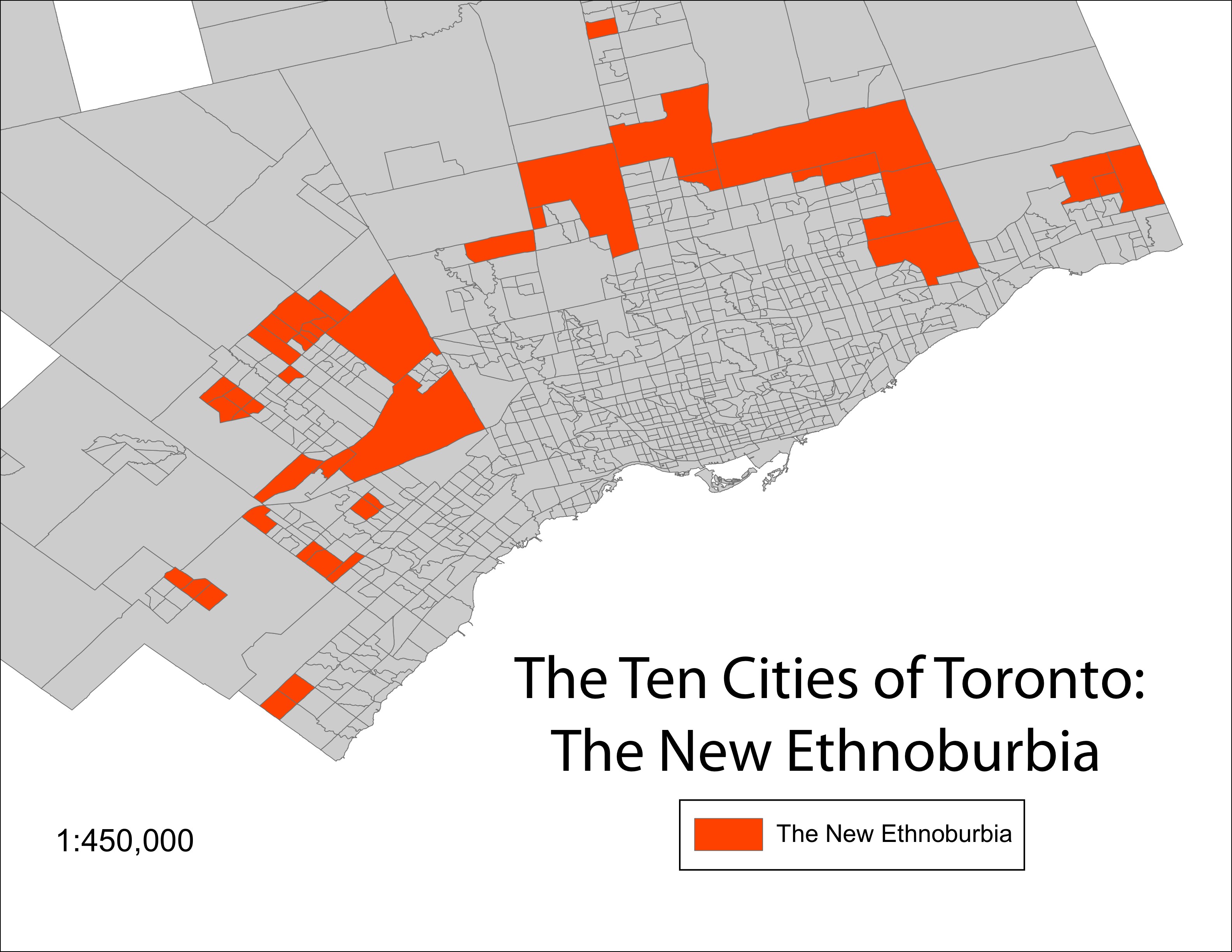

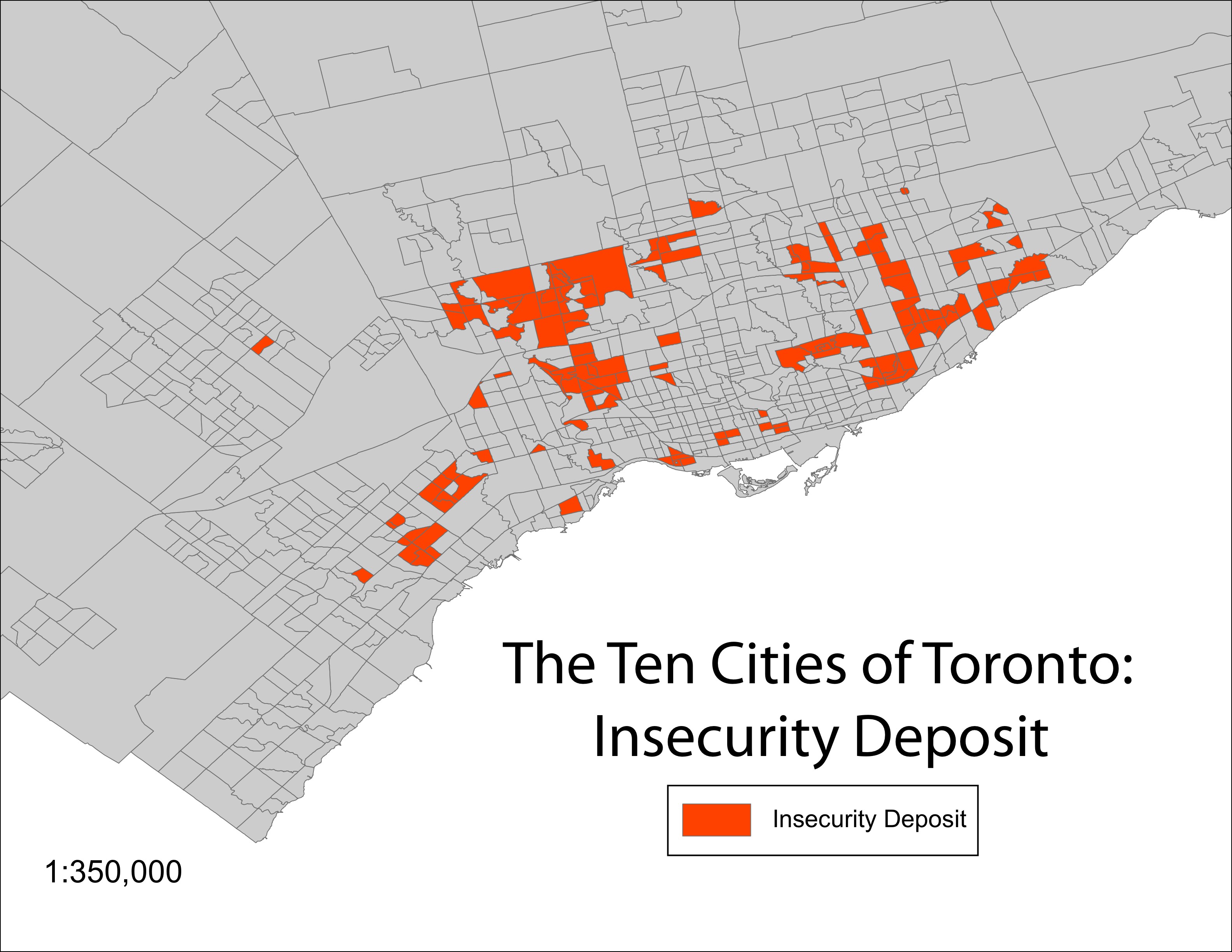

Data

The next stage in this research will be to map the specific patterns between immigrant households and tenure patterns, analyzing areas with many homeowners or renters, and the specific challenges these first generation Canadians face. This research however, can be unpacked in many different directions. Patterns of gentrification, decay, renewal, and expansion are illustrated through the various ten "cities." Take for example, the city termed "Go-Go Gentrification." This is a collection of neighbourhoods with high Gini coefficients (a measure of large income inequality), an outcome of wealthy homeowners moving into communities that previously were populated by lower income renters. These neighbourhoods, such as South Parkdale west of the business district, have become zones of contestation. The last parcels of affordable housing in the urban core are refurbished, sold to the highest bidder while the poor are forced out by higher rents and restrictive zoning ordinances (Slater, 2004). Other unique areas of the Toronto CMA also rise to the surface through this analysis. The "New Ethnoburbia" describes an area of rapid growth, housing many new Canadians on the rural-urban fringe of contemporary suburbia, while "Insecurity Deposit" captures the precarious housing status of many households, again many of whom are immigrants, living in high-rise, low-cost apartment complexes built as part of Toronto's suburbs constructed in the immediate decades following World War II.

Neighbourhood data has been collected through census tract - a boundary set out by Statistics Canada, measuring census data in groups of 4,000 people on average. In the data below, census tracts have been arranged into their respective "city," allowing for the examination of raw demographic data. With the results from both the factor analysis and cluster analysis, Toronto becomes represented as a fragmented landscape. Using the data compiled and additional secondary data from the Canadian Census, a number of research agendas are possible. Approaching Toronto through a view from above, these cities and the discussion attached to them are indicative of how the urban region of Toronto is being affected by a rising neoliberal policy agenda and uneven development caused by the invisible hand of capitalism (Harvey, 1978; Smith, 1986).

References

Harvey, D. (1978). "The Urban Process under Capitalism: A Framework for Analysis." International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 2(1-4): 101-131.

Hulchanski, D. (2010). The Three Cities Within Toronto: Income Polarization Among Toronto's Neighbourhoods, 1970-2005. Toronto: Cities Centre, University of Toronto.

Murdie, Robert. (2008). Diversity and Concentration in Canadian Immigration: Trends in Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver, 1971-2006. Toronto: Centre for Urban and Community Studies, University of Toronto.

Preston, V., Murdie, R., Wedlock, J., Agrawal, S., Anucha, U., D'Addario, S., Kwak, M.J., Logan.J., Murnaghan,A.M. (2009). "Immigrants and Homelessness - at Risk in Canada's Outer Suburbs." The Canadian Geographer, 53(3): 288-304.

Slater, T. (2004). "Municipally Managed Gentrification in South Parkdale, Toronto." The Canadian Geographer, 48(3): 303-325.

Smith, N. (1986). "Gentrification, the Frontier, and the Restructuring of Urban Space." In N. Smith and P. William (eds.) Gentrification of the City. Boston, MA: Allen and Unwin. Included in S. Fainstein and S. Campbell (eds.) Readings in Urban Theory. West Sussex, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

United Way of Toronto. (2011). Poverty by Postal Code 2: Vertical Poverty. Toronto: United Way.

Map by Liam McGuire

Map by Liam McGuire

Map by Liam McGuire

Map by Liam McGuire

Photograph by Liam McGuire

Photograph by Liam McGuire

Photograph by Liam McGuire

Photograph by Liam McGuire

"...the future form, character, and economic viability of this self-proclaimed global region have yet to be defined: will it emerge as a global financial and ICT centre or a post-modern centre of international culture, or will it settle in as a second-order city region within the North American urban system? Or, at worst, will it become a post-industrial Detroit North?"

Larry S. Bourne, John N.H. Britton, and Deborah Leslie (2011). "The Greater Toronto Region: The Challenges of Economic Restructuring, Social Diversity, and Globalization." In Larry S. Bourne, Tom Hutton, Richard G. Shearmur, and Jim Simmons, eds. Canadian Urban Regions: Trajectories of Growth and Change. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 236-268, quote from p. 237.

Photograph by Liam McGuire

Photograph by Liam McGuire