Gonzo Geography

If you have a few contrarian or dissident tendencies -- if you're a bit of a trouble-maker like me -- then consider the art, science, and revolutionary politics of gonzo geography. Here are a few of the names to search on as sources of inspiration: Bill Bunge, Steven Flusty, Nik Heynen, Don Mitchell, Mike Davis, Andy Merrifield, David Harvey, Noam Chomsky, Neil Smith, Saul Alinsky...

...or, of course, Hunter S. Thompson. Do you remember HST? Not long ago, a student was in my office interested in the history of utopian and revolutionary ideas in geography. Obviously, I had to mention the legendary Bill Bunge, whose intellectual arc from the late 1950s to the mid-1970s went from "spatial scientist" to "disciplinary bad boy" and "cult hero" (Heynen and Barnes, 2011). "The adjective 'Wild' often appears in front of Bill Bunge's name," Nik Heynen and Trevor Barnes observe. When Trevor conducted oral histories of the participants in geography's quantitative revolution, "there were more stories about Bill Bunge than anyone else..."; oftentimes "there were the instructions from some of the interviewees who, as they readied themselves to tell their Bunge story, would momentarily pause and say, 'This is where you turn off the tape recorder.'" (Heynen and Barnes, 2011, p. viii).

So of course I had to mention Bill Bunge's name to a student interested in geography's revolutions. But how should I describe him? How to summarize his adventurous and trouble-making path?

"Imagine that the field of geography had its very own Hunter S. Thompson," I mused aloud; "...that would be Bill Bunge."

As the words are coming out of my mouth, I realize how old and out-of-touch I really am. I see the blank stare in my student's eyes. She has no idea who or what the hell I'm talking about.

"Do you know who Hunter Thompson is...?" I ask in a timid, plaintive voice...

"No...."

I quickly recover my composure with a sudden brainstorm: "How about Johnny Depp, do you know Johnny Depp?"

"Oh, yes..."

Ah, common ground, and off the conversation went, and I recommended she see Terry Gilliam's delightfully faithful rendition of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, with Johnny Depp and Benicio del Toro. (Or, for a more panoramic documentary view, see Alex Gibney's Gonzo documentary.)

Yet that original source still matters: the written words of Hunter S. Thompson, and the development of a new way of writing that blurred all the familiar lines -- between observer and observed, subject and object -- just as effectively as the most sophisticated strain of Husserlian phenomenological social theory.

"The book began as a 250-word caption for Sports Illustrated," Hunter tells us, as he describes how he was having a hard time finishing a story of an allegedly accidental police killing of a journalist in Los Angeles, and how he jumped at the opportunity to get out of town for a few days to cover a motorcycle race in Las Vegas (Thompson, 1979, p. 105). Hunter "called Sports Illustrated ... and said I was ready to do the 'Vegas thing.' They agreed ... and from here on in there is no point in running down details, because they're all in the book."

"More or less ... and this qualifier is the essence of what, for no particular reason, I've decided to call Gonzo Journalism. It is a style of 'reporting' based on William Faulkner's idea that the best fiction is far more true than any kind of journalism. ..." (Thompson, 1979, p. 106).

At this point, when describing his methods, Hunter slips into a refreshingly cautious, clear modesty:

"...I should cut back and explain, at this point, that Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas is a failed experiment in Gonzo Journalism. My idea was to buy a fat notebook and record the whole thing, as it happened, then send in the notebook for publication -- without editing. That way, I felt, the eye & mind of the journalist would be functioning as a camera. The writing would be selective & necessarily interpretive -- but once the image was written, the words would be final; in the same way that a Cartier-Bresson photograph is always (he says) the full-frame negative. No alterations in the darkroom, no cutting or cropping, no spotting ... no editing." (Thompson, 1979, p. 106.)

Looking back on this today, we have to consider three separate issues. The first is that insistence on no editing. Thompson isn't really suggesting that a writer produce perfect prose the first time out, all in one seamless stretch of time and words from start to finish. Thompson clarifies that while he was indeed "writing feverishly" in a notebook during that famous 36-hour stretch in his room at the Mint hotel in Las Vegas, the "strange Vegas 'fantasy'" actually took shape elsewhere, in a room at the Ramada Inn in Arcadia, California, beginning with a week of short pre-dawn bursts of creativity, a series of "hard typewriter nights." It took about six months to finish the piece. Everything we know about Hunter makes it clear that the emphasis on "no editing" was about power, not procedure. It was about Hunter's desire to keep control over what he was producing. When he had sent an initial 2,500 words to Sports Illustrated -- instead of the tidy 250 they had originally asked for -- the piece was "aggressively rejected." The resistance to editing is about risk, and about trusting one's experience and vision to produce a bold, creative work. That should inspire us today. I hope it inspires you today, even if -- perhaps especially if -- you're a student writing a course paper for me. I'm trapped in a hierarchical system just like you are, and this means that I can't give everyone exactly the same top marks; but keep in mind that you have multiple opportunities to take risks in writing for me. I've given you an insurance policy to cover those risks, since I allow you to revise and resubmit if you're horrified with a particular grade. I can also assure you that a good challenge to convention or authority in the Hunteresque style will always earn my respect, especially if it's done well. What matters is the craft of scholarship, thinking, and writing: when it comes to opinions and politics and the like, I have no expectation whatsoever that you agree with me. Marks do not depend on your conformance with any particular orthodoxy. Marks are based on the way you gather evidence, organize your argument, and express yourself with clarity, creativity, and analytical force ... and perhaps just a bit of HST insurgence.

But there's a second important theme here, dealing with technology. Hunter ponders the notion of "the eye & mind of the journalist ... functioning as a camera." I think we need to be careful with Hunter's words at this point. He seems to be appealing to the camera in the familiar modernist spirit -- as the perfect device for recording, reflecting, or capturing the reality of all that happened. He's describing the camera just like Susan Sontag (1973, p. 5) did when she offered the just-the-facts observation that "Photographs furnish evidence." But of course it's not quite that simple, and Hunter knows this: it's not just the eye of the journalist, but "the eye & mind," and that makes all the difference. Sontag (1973, p. 4) also wrote that "To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge -- and, therefore, like power." Hunter understood this kind of insight, and indeed it's precisly how he lived and worked. Hunter's camera wasn't just some simple device for the passive recording of snapshots, but rather an "eye & mind" of power and provocation. Hunter loved to put himself in the most outlandish and hazardous of situations. Then he'd stand back and look at himself: not only would he observe his own reactions to all the strange people and events he had sought out, but he'd record the process by which he dove in and created the story himself. This is where the camera metaphor can be misleading, because it implies that Hunter was interested solely in recording what happened. Hunter made things happen, and then he turned his metaphorical camera on himself, and reacted with the same kind of bemused astonishment as did Roland Barthes (1981, p. 3) when he first encountered an image of Napoleon's youngest brother, taken in 1852: "I am looking at eyes that have looked at the Emperor." Barthes (1981, pp. 3-4) had his "ontological desire" to find out if photography existed in itself, if it had a "genius" of its own. Thompson, of course, had an entirely different kind of ontological desire. It came in the form of a red 1972 Chevy Impala convertible, with a trunk that

"looked like a mobile police narcotics lab. We had two bags of grass, seventy-five pellets of mescaline, five sheets of high-powered blotter acid, a salt shaker half full of cocaine, and a whole galaxy of multi-colored uppers, downers, screamers, laughers...and also a quart of tequila, a quart of rum, a case of Budweiser, a pint of raw ether and two dozen amyls."

My concern here is not with Thompson's infinite substance abuse (nor, for that matter, his strange obsession with guns); I wouldn't recommend that you live your life -- or end it -- the way Hunter did. Indeed, I don't have sufficient prurient expertise even to understand the scope of Hunter's molecular adventures as a passive spectator. I have no idea what I'm witnessing here. Battery acid? Laughers? What the hell is an amyl? No, my concern here is the active engagement with what it means to be a writer. Hunter was desperate to escape the boundaries restricting what it meant to be a writer in mid-twentieth-century America: he wanted to destroy the traditions of a detached objectivity that required the writer -- particularly the journalist covering, say, a political campaign -- a passive instrument for conveying information in a neutral, even-handed manner. This is why Hunter jumped in to the stories he was writing, in order to create the story; this is also why the camera metaphor is misleading, unless you happen to have a camera that drives fast, yells at people, writes until dawn, and sometimes just makes shit up. Yes, of course, I'm sure that the technology is coming, and soon enough we'll have some sort of fancy device that does all those things; we already have software that writes news stories, and then other firms have software that automatically "reads" the news (Lohr, 2011; Arango, 2008). We are venturing into a dark and depressing place indeed, where we are rapidly losing the humanity of writing. We lost hunter in 2005, before Web 2.0 and the social networking obsessions of our current age, but even technology advocates have begun to rethink the benefits of a post-human world. Not long ago, Jaron Lanier (quoted in Kahn, 2011, p. 47) began a talk at the South by Southwest Interactive conference with a stunning request: he asked the audience to refrain from blogging, tweeting, or texting while he spoke. "He later wrote that his message to the crowd had been: 'If you listen first, and write later, then whatever you write will have had time to filter through your brain, and you'll be in what you say. This is what makes you exist. If you are only a reflector of information, are you really there?'"

Now stop and think about this. The request was stunning not only because of the setting -- a conference of bleeding-edge technorati -- but also because of the biography of the speaker. Lanier was a pioneer of what we now describe all all too casually as "virtual reality," and he is often credited with developing the phrase itself. And he's asking you to put aside the technology, to listen and take enough time so that information can filter through your mind, so that you will be in what you say. This is deliciously revolutionary. It's also quite a challenge, since it goes against the temptations nourished by a powerful infrastructure of hard-sell marketing that now assualts the human attention span at every turn. The newspaper, that quaint invention struggling to survive in a post-paper, post-literate age, tells me that "Location, location, location is being replaced by attention, attention as the new mantra for businesses looking to succeed in today's digital economy." (Shaw, 2011, p. 3). What, did you say something? ... say all the people as they look up from their BlackBerries. In the other room, I hear the television blaring out Microsoft's latest ad for Windows 7, which by the time you read these words will be a long-forgotten technological blip on the way to whatever technofetish is currently all the rage. But the closing line of the ad will be as unintentionally hilarious and frightening then as now:

"I'm a PC, and I'm finally up to date."

Finally up to date? Has our notion of finality evolved into an experiential derivative, a rate-of-change measure of bragging rights of consumers clicking "buy" faster and faster, as fast as their credit cards will allow? Pierce (Nettling, 2011) is quite right that there's nothing romantic about Microsoft Word; there's also nothing stable about such innovations. The pace of creative destruction is quickening, and there are no guarantees that the new is inherently superior to what it's destroying. All we know is that we're constantly asked (forced) to update, and to do so more more frequently. This is the digital runner's paradox.

No matter what kind of speedy new technology is introduced today or tomorrow, writing must remain a human activity. Soon, the marketers will promise that the machines can, in fact, do the thinking and writing. As I noted above, software bots are already being used to write basic news stories (Lohr, 2011). At the same time, Wall Street firms have been using software bots to "read" news accounts and execute equities trades automatically on the basis of positive and negative content about particular companies or sectors. The bots aren't yet as smart as they think they are: a six-year-old story about a bankruptcy filing by United Airlines somehow resurfaced and zipped around the web, triggering an avalance of automated sell orders; about $1 billion of market capitalization was vaporized within twelve minutes (Arango, 2008). But Wall Street's computer scientists and linguists will fix the bugs, and accuracy surely will improve. As the bots get better at reading and writing, the humanity is being stripped away from those most human of activities. Perhaps this explains why I am unable, even at this late date, to pull myself away from that antiquated human technology -- the pen marching across paper, driven only by the velocity of human thought.

His metaphorical pursuit of the presumed perfection of a device that is all too often regarded as a passive means of recording reality -- the camera -- belies the importance of the active work he did on an entirely different kind of device. The other device, of course, is what Hunter calls "this noisy black machine," his Selectric typewriter.

Third, the separation of the observer and the observed; bureaucratic and legal restrictions and advertising...?. Hunter was clear that he was working in the twilight of freedom in that respect...

(still working this stuff out, will refine and rewrite later in another pre-dawn HST moment...)

spending an increasing share of our attention span updating whatever technological fetish is being pushed upon us

one thing that keeps us grounded is the sense of embodied -- writing is, or should be done physically, and should involve the inescapable humanity of the body. touch...touch in writing...

thinking is hard

no matter what device we come up with, we are still going to have to tell it what to produce...

sontag

pierce nettling taylorized alienated..

Disclaimers:

References

Arango, Tim (2008). "I Got the News Instantly, Oh Boy." New York Times, September 13.

Barthes, Roland (1981). Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux.

Bunge, William (2011 [1971]). Fitzgerald: Geography of a Revolution. Athens: University of Georgia Press / Detroit: Schenkman Publishing Company, Inc.

Heynen, Nik, and Trevor Barnes (2011). "Foreword to the 2011 Edition: Fitzgerald Then and Now." In William Bunge, Fitzgerald: Geography of a Revolution. Athens: University of Georgia Press, vii-xv.

Kahn, Jennifer (2011). "The Visionary." The New Yorker, July 11/18, 46-53.

Lohr, Steve (2011). "In Case You Wondered, a Real Human Being Wrote this Column." New York Times, September 11, p. BU 3.

Nettling, Pierson (2010). "The Archaic Typewriter: Training Tool for Student Writers?" The Nation, "Extra Credit" Blog, September 15.

Shaw, Gillian (2011). "Next-Gen Entrepreneurs and Customers in a Changing Landscape." Vancouver Sun, August 19, p. C3.

Sontag, Susan (1973). On Photography. New York: Picador.

Thompson, Hunter S. (1971). Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey into the Heart of the American Dream. New York: Vintage.

Thompson, Hunter S. (1979). "Jacket Copy for Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream." In The Great Shark Hunt. New York: Simon & Schuster, pp. 105-111.

Writing

Reflections, advice, and confessions

Elvin Wyly

We live in a world of accelerating technologies, and Schumpeter is on crack. There seems little doubt that the treadmill of technological innovation is kicking into ever higher gear: is Moore's Law juiced with steroids?

The hamster wheel of computer and communications technology presents us with inescapable contradictions. Never before have we been able to locate, store, search, relate, and synthesize such vast quantities of information. Never before have we been so overwhelmed and paralyzed by such vast quantities of information, unable to make sense of it all. Inflation is out of control in the information society: too much information, not enough wisdom, analysis, and reflection.

If you're having trouble beginning the writing process, you may find some of the notes on this page helpful. Then again, you may not. I make absolutely no claims to be able to write well: it's often quite a struggle for me. But I love the struggle, and if any of my experiences are helpful for you, then I'm happy to bare my soul and reveal my very personal moments of fear, frustration, joy, and occasional jubilation. Ignore my advice if it seems irrelevant, uninteresting, or counterproductive. Do what works for you. (If you're a student searching for the way to translate "what works for you" into "good grade on a term paper due tomorrow," this page won't help much; you have multiple opportunities to try various approaches, make mistakes, and obtain feedback -- see the deadlines and guidelines on revised submissions in the course syllabus.)

The Craft of Writing

- craft (kræft, kraft) n. a trade or occupation that requires skill in the use of the mind and hands, the craft of painting || an art viewed as a making that requires developed skills, the craft of fiction || the members of a trade collectively, a guild || cunning, deceit, guile || (pl. craft) a boat or vessel or aircraft [O.E. crœft, strength, skill]. Bernard S. Cayne, ed. (1990). The New Lexicon Webster's Encyclopedic Dictionary of the English Language. New York: Lexicon Publications, p. 226.

I learned to write in the very early years of the mass diffusion of personal computers. Yes, I was born in the Pre-Cambrian. Personal computers and word-processsing software applications were (comparatively) scarce, expensive, unreliable, incompatible, and otherwise difficult to access. At least in the first few years of my university experience, most students arrived on campus not with computers, but with portable electric typewriters. At first it was only the rich kids who came with computers (often proudly stuffed into the Beemers they pulled up to unload at the dorm), but very soon, others gained access as well. Almost immediately the arms race began, with the elite claiming bragger's rights in the pursuit of ever newer, faster machines with ever more impenetrable terminology boasting of various technological gizmos and capacities. Processing speeds took off, and storage capacities galloped ahead with new devices and standards each year. The Prefix Wars raged on, as kilo gave way to mega, which was routed by giga, and is now under assault by tera. Looking back on those days, one has to laugh: there was a time when the Commodore 64 was the latest cool thing, because it had a whopping 64 kilobytes of random access memory, which really put the old Vic 20 to shame.

But that Commodore 64 hints at some important, non-linear aspects of the diffusion of computer technologies in this period. I had one of those things in eleventh grade, and I learned how to write a few elementary programs on the thing, achieving such profoundly important tasks as showing a sequence of bright colors while various annoying tones blared out of the television attached to the silly device. Yet I never mistook that Commodore 64, nor any of the other quirky things proliferating on the market, for anything other than a computing device. And a computing device was not a writing device. Very early on, I came to see computers in a very particular role. Computers were for games, or for calculations, or for organizing and storing information. In later years, when I gained access to the monstrous mainframe in the dedicated computer building on Penn State's campus, I understood that computers were ideally suited for running really cool database management and statistical programs and creating fancy color three-dimensional graphics of the results. I spent many late evenings submitting code and then waiting in line at the output window to get that stack of big green tractor-feed paper with my name on it. Computers were great for lots of things.

But not writing.

Writing meant something different. It meant writing out various notes, ideas, quotes, references, outlines, partial and disorganized paragraphs, and scores of plaintive 'note to self' scribblings. Most of those scribblings wound up crumpled on the floor. Others were more fortunate. If they were good enough or within easy reach at the right moment as a deadline loomed, they made it into a first draft that actually got typed. The really good ideas, words, phrases, sentences, and even entire paragraphs might survive the next draft. And perhaps the next.

All of this implies an amicable, yet ambivalent, relationship to technology. Consider four crucial points.

1. First, generational comparisons matter. In the pre-computer age, students took just as many classes as they do today. They had to balance all the same kinds of demands of life and work outside the university while juggling all the challenges of university-level classes, not to mention the ubiquitous demands of most university bureaucracies. Having a super-fast microprocessor and unlimited storage capacity meant nothing (unless, of course, you were specializing in a field like computer science or electrical engineering where these technologies were central to the learning enterprise itself). Instead, what really mattered then -- and still does today -- was reading, thinking, analyzing, and writing. Students of a generation ago had to write papers too. They did it, even without email, the internet, and the latest lightning-speed processor. The scholarship produced a generation ago was different in important ways from what students, teachers, professors do today. But different does not mean inferior -- nor superior (I am not one of those cranky, we-walked-uphill-both-ways-to-school types complaining about "kids these days..."). My point is that generational and technological contrasts often obscure the underlying continuity of human thought and human labor. Computer capacity has certainly expanded dramatically since the days when I first began storing notes and stuff on one of those 5.25" floppy disks; now I have a device in my pocket that can store 3,809.52381 times as much information.

Now, think: are we able to write papers that are 3,809.52381 times better than what was produced on pen, paper, and typewriter?

2. Second, reading, thinking, analyzing, and writing cannot be automated. Yes, the latest speedy laptop and wireless connection can quickly get you to vast library collections of books, articles, numerical data, and other resources. Some of these capacities are indeed new, and they are getting better in many ways. But these should not be confused with reading, thinking, analyzing, and writing. Access, storage, collection, and searching are useful indeed, and I encourage you to use every technology that helps you move through these phases of your inquiry. But the real heart of what we do in the academy happens in the mind, where megaherz and terabytes run into the slow realities of biology, chemistry, and the neurological limits of the human brain. At this point, unlimited computing capacity meets the limits of humanity. Am I the only one who feels a little bit dehumanized by this process? A generation ago, we could take solace in the idea that although computers were really important, they would never really have the capacity to think like us human beings. My old Commodore 64 only had 64k! But after all the hundreds of Terminator-style artificial-intelligence-gone-wrong movies we've been subjected to, and in a world where automation is all the rage, is there any role for us, as thinking human beings? I confess: I feel more than a little bit of anxiety when I realize that my primitive little brain has a slower processing speed and less memory than, say, my microwave oven.

3. Third, embrace the passion and the pain. This is not a cynical or depressing story. The processing speed of the human brain may be limited, but the human imagination is not. The possibilities are endless, and I want you to savor that kid-in-a-candy-shop excitement that first brought me into geography (if you want to know the details of what did it for me, see this). My point here is simple: do not make the mistake of confusing activities best done by computers with the things that define our humanity, that nourish and sustain our minds as scholars, students, citizens, workers, children, parents, brothers, sisters, and trouble-makers. Use the latest technology when it's useful, but do not rely on it -- and do not allow it to deny you the passion, pain, and pleasure of thinking, analyzing, and writing. Peter Gould once wrote an essay on this: he titled it "Thinks that Machine," a deliberate reversal of the machines-that-think fetishes of artificial intelligence research. Think creatively, and don't allow yourself to fall into lazy, mechanistic thinking. And do not deny yourself the experience, the human craft of writing.

4. Fourth, respect the craft of writing. In practical terms, what does this all mean? I can only speak to what works for me. For searching, collecting, organizing, communicating, and other things that might best be defined as "playing around with stuff," computers are great, and I use them a lot. I work with both Mac and PC, on a combination of pathetic old beasts and comparatively less pathetic, less slow devices. I have no desire for bragging rights on fancy computer stuff. But when it comes to writing, what matters most to me is the craft -- that very first definition at the top of this page, "skill in the use of the mind and hands" really matters for me.

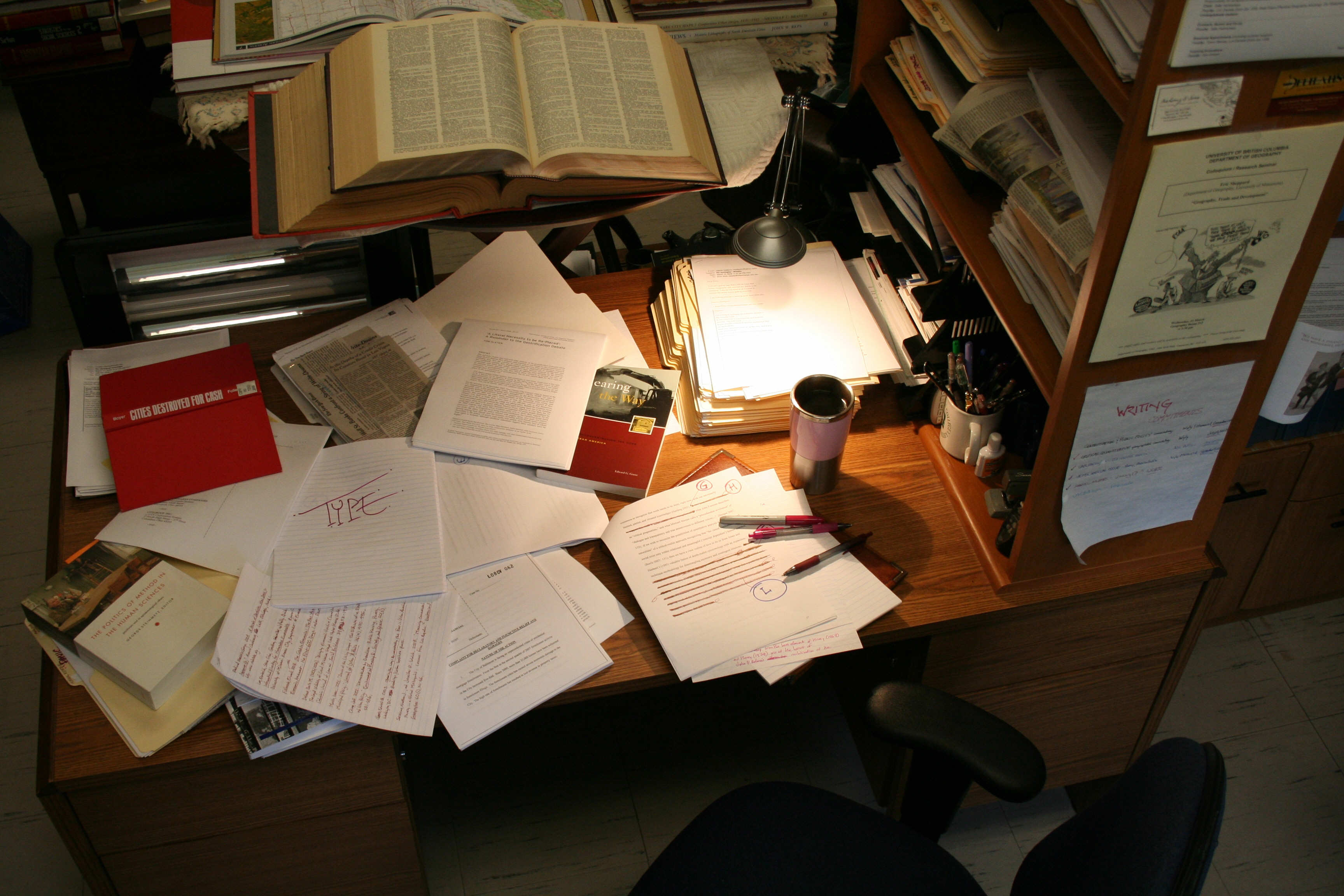

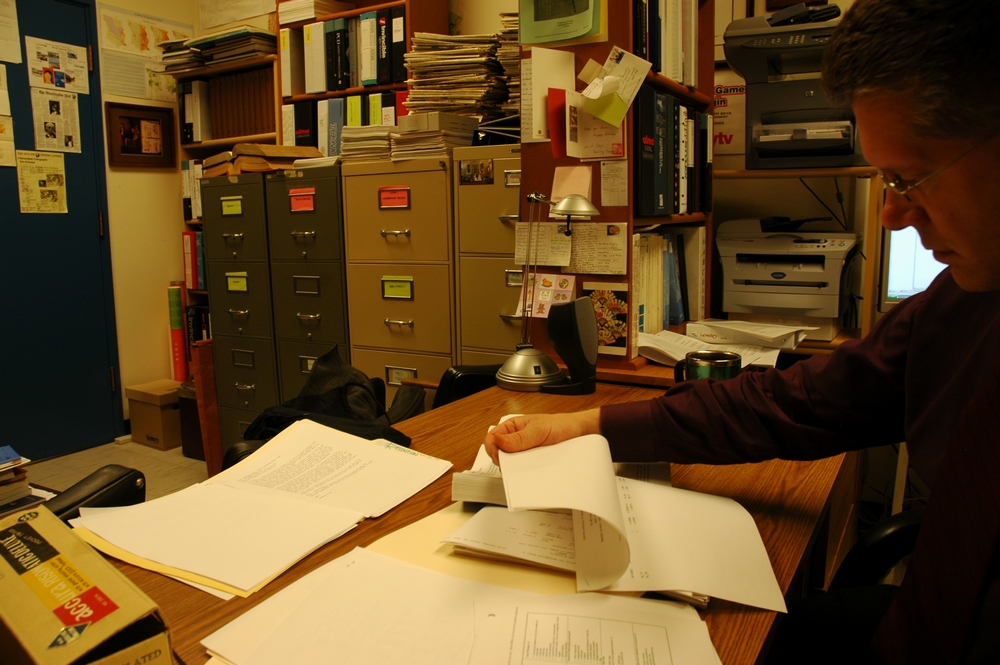

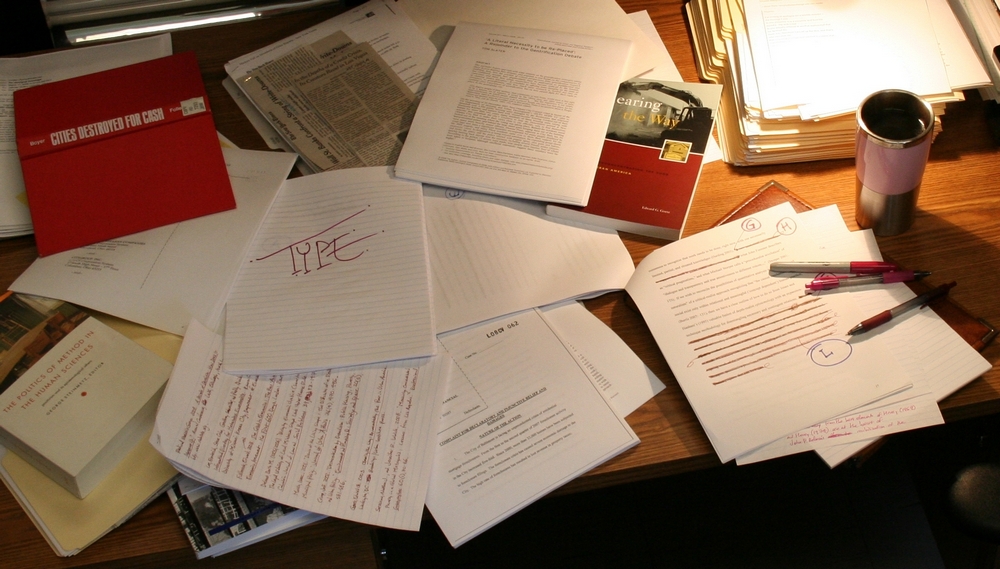

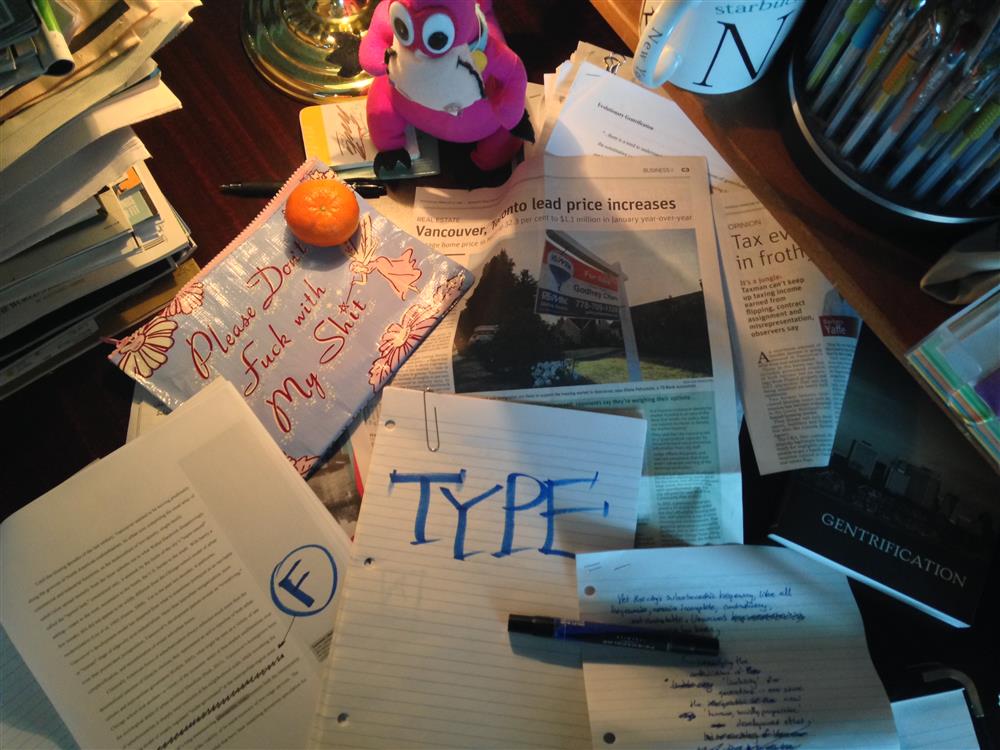

Look at that desk at the top of the page. See a computer? For me, writing is just that -- writing. I'm just as capable as the next person when it comes to the ability to type things and compose at the keyboard (keep in mind that I took a typing class in high school, and had to ignore a lot of the harassment of other guys, because this was back when typing was very clearly feminized both in the workforce and in educational systems; I was one of two males in the entire class of thirty). But when it comes to writing formal scholarship, I sit down, take out my pen, and begin to write. Yes, it is slow. But keep in mind what I noted above -- this is not about speed, but about thought, reflection, and organized expression of original ideas backed up by citations to the work of others -- others in the academy, in the realms of policy, in the press, or on the streets. If we try to compete on the basis of speed, we will lose to the computer every single time. And slow progress is still progress. If you write just a few hundred words every morning of your work week, you'll be amazed how much good work you're able to create. (For further thoughts on the issue of pacing yourself on writing projects, see my reflections on ABW on the right side of this page). I write for a short period of time most mornings -- at least when I'm a good boy and I take the advice I'm giving you -- and then when my stack of paper with arrows and letter-coded inserts becomes too difficult to make sense of, then I sit down and type a draft. Then I print it out and continue writing by hand, chopping some things out, revising others, adding new material, all with more and more of those letter-coded inserts in a stack of paper with "Type Me" on the top.

Writing in this way is slow, and maybe it's thoroughly old-fashioned and un-cool. I know that I may very well be exposing myself to infinite global ridicule with my very public admissions. But here are a few of the reasons why I do it.

- It imposes a discipline of thought and commitment. When I compose at the keyboard, I'm exposed to unlimited temptations to check email, read the newspaper, sift through a blog, or do any one of a dozen other things that distract me from writing. When there is a blank sheet of paper in front of me, and a pen in my hand, I know what I need to do. I am also forced to think clearly and to express myself coherently -- because if I write a sentence that makes no sense, that's fine, but then it will cost me the effort to cross it out and start afresh. Typing at the keyboard allows one to create, revise, and delete an infinite number of words, sentences, and paragraphs. This is great. But it should not surprise us that when we reduce the marginal cost of lazy thinking to zero, we encourage ourselves to slip all too easily into ... well, a lot of lazy thinking. And Howard Becker cites research on the process of writing that essentially concludes that writing is best understood as a form of thinking.

- Writing by hand makes it absolutely impossible to plaigiarize, even accidentally. If you're writing out things by hand, there is no way that you will mistake the mechanistic activity of transcription with the creative activities of coming up with your own words. And "cut and paste" means just that -- it's not the metaphorical button in the word-processing package. These physical activities -- skill in the use of the mind and hands -- provide powerful reminders to cite work that is not your own. (As a further shocking confession, I will also admit to you that I write out every citation by hand as well. I know there's a lot of automated "citation management" and bibliographic software out there. Use it if it works for you. But do not let it become just another distraction from the craft of thinking and writing.)

- The handicraft approach reinforces the spirit of originality, investment, and creation. Word-processing packages make it easy to dash off quick notes and sudden thoughts. This is great, but it's not writing. Similarly, voice-recognition software helps to capture sudden flashes of inspiration and imagination, and I'm sure that next year we'll have a little patch we stick on our head to translate our every thought into audio, video, or textual output. Once again, though: do we really want to surrender the passions and pains of writing -- in all its humanity, across generations going back to Gutenberg and centuries before that -- to any device? Have we so completely lost our humanity that we are willing to surrender our skills to the automated promise of "error-free manuscripts in seconds!"? When you write by hand, you've made a commitment and investment that has forced you to think carefully, to think twice or three times about important decisions, and you have, quite literally, created something where before there was just a blank sheet of paper. You can see those words clearly as the work of your mind and your hands. They are yours. (I acknowledge that this does have its drawbacks. It sometimes makes it hard to be as ruthless as necessary when you've gotten feedback from someone else that requires you to make major revisions, especially when it involves cutting out large sections of material. But I'm getting a lot better at that).

My final confession: I came in early this morning with the plan to follow my own advice, to write fresh early in the morning for just a half hour, but then I succumbed to temptation -- to put together a few notes and documents I've written at various points in time, add a bit, and produce this rather embarrassing, confessional web page. In other words, I committed wanton and sustained violation of the ABW rule. See how easily I'm distracted? Now it's 5:15 PM. I think I might be able to get about thirty minutes of good writing time if I pull myself away from this computer...

After the Proposal

For upper-division seminar courses, I establish a series of deadlines for the submission of a paper/project proposal, first draft, second draft, and then a final paper deadline. The most exciting moments of possibility and hope come when I read the proposals, which are usually submitted about four weeks into the term. Most are quite good, and usually there are at least half a dozen that are truly outstanding. The range of ideas, topics, and plans is always wonderfully fascinating and valuable. I always do my best to write helpful, constructive comments, questions, and reactions on the individual proposals. And in the spirit of collaboration and 'barn-raising' as described by Michael Kahn, I encourage students to share their proposals with other colleagues in the seminar or workshop. Somehow it doesn't seem fair that I be the only one to have the privilege of reading through all of the proposals.

If you're interested, here are a few of my general impressions after reading and thinking about all the different proposals I've received in the last few years for the Seminar in Urban Studies. These suggestions are offered in the spirit of constructive criticism -- the scholar's ethical responsibility to go beyond simply identifying problems or limitations, in order to provide specific advice on how to improve things. Not all of these comments will be relevant to everyone. Feel free to ignore the suggestions if they don't seem relevant or helpful.

1. A nice short proposal is the first step on the way to a first draft. Start working on your project, and note the date on the syllabus for your next opportunity for feedback.

2. As you work on your draft, keep the spirit of initial enthusiasm that most of us feel when we've written out a short proposal. It's not uncommon to lose this spirit after working on a project for many weeks or months, with all the other responsibilities and commitments we have. As we begin fleshing out proposed ideas, however, it is possible to maintain this initial enthusiasm and sense of possibility. Two strategies are most valuable. First, ABW.[i.] Always be writing. On any given writing project, carve out fifteen minutes of pure, uninterrupted writing time each working day; the rest of your workday can be devoted to whatever mix of responsibilities you have, but if you spend those fifteen minutes writing, slow and steady, you'll be amazed at how much good scholarship you can produce. [ii]. Second, approach your writing project as an ecological process, not a formulaic straightjacket or a final, perfect, reporting-of-results activity that you do at the very end of the project right before the deadline. Avoid the Final Copy Syndrome: the mistake, which is very easy to make as we read books and articles published by leading scholars in top-tier outlets, of believing that the final, published version of a piece of scholarship was written from beginning to end in a carefully organized progression. Most good works are written from the inside out, and reorganized many times, with things like an introduction added only at the very end. Yes, the final, published version of a written work should be well organized, with a logical, smooth flow from one section to another. But this logical flow is meant for the reader: the process of creating that logically organized piece of writing is often quite dynamic, subject to many changes, and often rather messy.

If you follow the ABW advice and avoid the Final Copy Syndrome, it will make it much easier to maintain that initial sense of proposal enthusiasm as you do your research while juggling all the other things you have to do in your busy schedule. You won't keep waiting for a single, magical bolt of inspiration and sudden realization of how to do a particular kind of scholarship and how to write it out clearly. [iii.] Instead, you'll spend a little bit of time each day producing new scholarship, while some of the other hours in the day can be spent reading and doing research you realized you needed to undertake when you got to a particular part of the writing, and you'll go back and forth in this iterative, ecological reorganization, revision, and re-writing.

Revision and rewriting are essential. Everything is a first draft, second draft, n-draft. Consider these reflections, from the eminent sociologist Howard Becker, excerpted from a delightful chapter he titles 'One Right Way':

"I have a lot of trouble with students (and not just students) when I go over their papers and suggest revisions. They get tongue-tied and act ashamed and upset when I say that this is a good start, all you have to do is this, that and the other and it will be in good shape. Why do they think there is something wrong with changing what they have written? Why are they so leery of rewriting?"

"...often, students and scholars balk at rewriting because they are subordinates in a hierarchical organization, usually a school. The master-servant or boss-worker relationship characteristic of schools gives people a lot of reasons for not wanting to rewrite, many of them quite sensible. Teachers and administrators intend their schools' systems of reward to encourage learning. But those systems usually teach undergraduates, instead, to earn grades rather than to be interested in the subjects they study or to do a really good job ... Students try to find out, by interrogating instructors and relying on the experience of other students, exactly what they have to do to get good grades. When they find out, they do what they have learned is necessary, and no more. Few students learn (and here we can rely on our own memories as students and teachers) that they have to rewrite or revise anything. On the contrary, they learn that a really smart student does a paper once, making it as good as possible in one pass...."

"Schools also teach students to think of writing as a kind of test: the teacher hands you the problem, and you try to answer it, then go on to the next problem. One shot per problem. Going over it is, somehow, 'cheating,' especially when you have had the benefit of someone else's coaching after your first try. It's somehow no longer a fair test of your own abilities. You can hear your sixth grade teacher saying, 'Is this all your own work?' What a student might think of as coaching and cheating, of course, is what more experienced people think of as getting some critical response from informed readers. ... "

"Students don't know, never seeing their teacher, let alone textbook authors, at work, that all these people do things more than once..."

"..revising and editing happen to everyone, and are not emergency procedures undertaken only in cases of scandalously unprofessional incompetence." [iv.]

3. The logical implication of Becker's reflections on writing and rewriting is to trust yourself as you begin crafting outlines, plans, notes, and ideas. Don't aim for perfection on a first draft. Some writers crank out messy, disorganized sentences with lots of typographical errors that still manage to present a coherent and compelling analysis; once they're happy with the big picture, they go back and clean up the spelling errors, grammatical gaffes, and the like. Other writers labor over carefully-constructed sentences, starting from a few scattered points in the overall project; each sentence reads perfectly, but the big picture is hard to see amidst the fragments. Either path can work well. But both require daily doses of ABW.

Trusting yourself does require trusting your reader, however, and I understand that this can be difficult. That's why Becker's bottom-line is so crucial: revision happens to everyone. Nearly everything you read in books and articles has been revised, often quite a lot, from the initial version. Catherine M. Wallace puts it this way: "Revision is continuous; it is incessant; it is a vital part of the writing process. Revision is the renewing and the development of vision. Re-vision is the effort to see and to develop further what's right about a piece, what's good, what's successful and engaging. We need re-vision because our very best work comes from such deep levels of the psyche that we are never fully conscious of what we are doing" [v.] -- until, that is, a careful, critical, and constructive reader helps us to develop that consciousness.

Critical feedback is valuable, but many of us fear it, because of the meanings we assign to words like "critical." Too often, criticism is understood solely as finding fault: "...university culture assumes that to engage seriously with anything is to look for faults and flaws and problems. What's good gets brushed aside; what's bad becomes the center of attention." [vi.]

I rebel against this orthodox strain of university culture, and so should you. To be sure, finding faults (or what is better understood as proof-reading or copy-editing) has its place, and I do mark lots of these on many paper submissions. But I also scrawl sorts of words of appreciation, admiration, and exclamation on various parts of each manuscript. "Fabulous!" "Wonderful!" And I beg for more at various points. "I don't understand this." "Can you tell us more?" Or just, simply, "?"

4. As I mentioned earlier, I am impressed with the exciting range of interesting ideas that many people have described. Some of the proposals, however, remain in the realm of topics, themes, or ideas: they leave out what makes a proposal most interesting -- the description of how the scholar will undertake specific activities that will achieve the goals. Methodology matters. The more specific you can be in describing your methods of analysis, the more helpful the proposal will be for your own purposes. When it comes to methodology, specific plans are often tentative and provisional: you'll discover that an initial plan didn't work; an unexpected path will suddenly open up in a place you had not expected. Revise your plans accordingly: changing course like this is not a sign of trouble, or a failure of any kind. [vii.] What matters in methodology is not (as Becker would put it) finding the One Right Way - there are often many different, complementary methodological routes to the same destination. But it is essential to have a clear sense of how to break down a big question into manageable, discrete tasks that will yield the kinds of evidence you need. Neglecting the methodological question usually results in an accidental methodology. [viii.]

If you need advice on a particular methodology, consult the extensive Research Methods series published by Sage Publications, Inc. They have an impressive array of books on the many different kinds of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods approaches. [ix.]

5. As you begin working on your draft, place a high priority on evidence. Back up your claims and interpretations with the kinds of evidence that are honored by your audience. Carefully avoid slipping into the Inadvertent Opinion Piece: anytime you offer your opinion or tell the reader what you think, you accept the burden of laying your credibility on the line. If your audience knows you've got the reputation and expertise to back up an opinion that you've tossed into the conversation, that's fine. If not, then your opinion could be easily dismissed unless you provide the kind of specific evidence that your audience has to accept.

I don't mean to dissuade you from offering opinions and interpretations. Instead, I'm advising you to avoid the inadvertent opinion -- the kind of writing that is too easy for all of us to slip into when we're facing a deadline, trying to add originality and interpretation to a piece of work, and we need filler for a particular section. Venture your opinions and interpretations with the clarity and confidence that comes with time and expertise -- as you've worked out bits and pieces of the interpretation in those small writing blocks each day, week after week, giving you time to marshal compelling evidence for your views.

6. One of the other chapters of Howard Becker's wonderful book is titled, "Terrorized by the Literature." Don't be. There are more than 160 thousand pages of written material produced in the English language alone every single day. [x.] You can't read it all. Neither can I. Don't be Terrorized by the Professor, either -- thinking that whatever you're reading, I've read it too, and I'm there looking over your shoulder to make sure you get everything perfect. And just to be clear: I don't want to tell you what to think. I am much more interested in how you think. I impose no party line or political orthodoxy: I am not looking for the 'right' answer or interpretation. What impresses me is the art and science of compelling, rigorous, analytical scholarship: play to your strengths, and use whatever skills you have to create a narrative, analysis, interpretation, synthesis, or model that helps you to develop, express, defend, and refine your own views on important matters.

Footnotes

i. I first thought of this in the midst of an intense writing commitment many years ago. Procrastination involved watching Jack Lemon, Alec Baldwin, Kevin Spacey, and Ed Harris in Glengarry Glenross. Baldwin's ABC -- "Always Be Closing" inspired me to get back to work (after the final credits rolled).

ii. This is a minimum, and it's a guideline: do fifteen minutes, thirty minutes, forty minutes, an hour, whatever time you can devote to pure, uninterrupted writing. If you have three writing projects, of course, then you must carve out and protect fifteen minutes every day for each one of them. If you answer a phone or check email, the counter resets to zero: honor the need to protect this time slot for writing and nothing else.

One other caveat: the fifteen-minute advice assumes that you've begun writing on your project promptly -- say, a few days after receiving my comments on your proposal. If you wait until two weeks before a final deadline, no, I'm sorry, this advice is simply not going to work for you, and there's not much I can do to help you. The amount of time you devote each day to a writing project is not what matters; what's really crucial is that you keep coming back to it, day after day, each day with fresh eyes and fresh energy, and you quickly build up momentum. If you wait until the very last minute, you're just going to have to use the very risky, dangerous approach of, say Hunter Thompson or Tom Wolfe.

I received this advice through an intensive all-day scholarly writing workshop sometime in 1996. I forget the professor's name, and it's buried deep somewhere in my disorganized files. He told us that if we followed his advice -- some of which seemed deceptive, simplistic, and patronizing -- that it would work, and we would probably hate him for teaching us such simple lessons. He was right. The most crucial part of the advice is to keep writing each day, consistently: fifteen minutes a day, every weekday, for five weeks, is only five hours. But if you write on that schedule, you will probably be much more productive than if you write nothing for the month, and then try to work in one solid five-hour block. You're unlikely to work that entire solid block of time without taking multiple breaks. Moreover, there is a powerful, cumulative effect when you write for short periods of time every day. During that pure, uninterrupted writing time, you're able to capture many of the ideas and associations you've had during the rest of the day. In other words, in that rest of the day when you're not writing, you're actually freed to do a lot of thinking that will eventually get written down in your next day's pure, fifteen-minute writing slot. I recommend that you always have a small notepad with you, so that you can scribble down ideas that occur to you when you're doing other things. Use these notes in your very next fifteen-minute writing slot -- it's easy to remember what you meant in a cryptic note written on a bumpy bus ride if you look at it the next day, but you'll never figure out the scribbling if you wait for weeks or months to try to write it out. My writing life is governed by the Inverse Convenience Law: the probability of having a useful or creative insight is inversely proportional to the convenience of the situation in which it occurs.

iii. For some people, this approach does work. If you're one of them, then feel free to ignore all of this advice. But this strategy is quite risky, and most of us are mere mortals, only fortunate enough to have a few miniature flashes of inspiration rather than one big revelation. One day we get a good idea for how to study a particular thing; the next day we might have a really good, coherent reading experience; the next day might be more productive than usual for our fifteen-minute writing block. Few of us have a sudden 'grand' epiphany that combines all of these at the same time, just in time to finish all of the research, reading, writing, and editing right before the deadline.

iv. Howard S. Becker (1986). Writing for Social Scientists: How to Start and Finish Your Thesis, Book or Article. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 43-45. I also recommend Howard S. Becker (1998). Tricks of the Trade: How to Think About Your Research While You're Doing it. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. These volumes are part of the valuable Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing.

v. Catherin M. Wallace (2008). "Care & Feeding of the Work in Progress." Writer's Chronicle 40(5), March/April, 53-59, quote from p. 55.

vi. Wallace, "Care & Feeding," p. 56.

vii. Major course changes in methodology are problematic, however, if you've waited until the last minute and you're up against a deadline when you realize, halfway through writing, that you can't seem to explain things in a way that will make sense to you, or to your audience.

viii. In other words, if you don't clearly specify, for you and your reader, your methods and standards of evidence, the final product will probably have a research design that is best described as "I read everything I could on the subject given the time that I had, and then right before the deadline, I hurriedly wrote something to try to put these readings together in an original way." Sometimes, this works fine. But it's risky, and it's terribly easy to get lost in that first step, reading everything you can find on a particular topic. One simple way to avoid getting lost is to clarify a purpose that helps you to decide what you'll read and why: "To analyze how disciplinary traditions shape the way this urban issue is framed, I read the table of contents and introductory chapters of the two leading textbooks in each of five different disciplines - economics, sociology, geography, history, and urban planning. I compared the way questions were posed, the levels of analysis and units of observation..." and so on, and so on, you get the idea.

ix. There are scores of methods texts in each discipline, so explore the ones that seem most comfortable to your home discipline. A few within reach on my bookshelf are: Nicholas J. Clifford and Gill Valentine, eds. (2003). Key Methods in Geography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; Stuart Aitken and Gill Valentine, eds. (2006). Approaches to Human Geography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; Sarah L. Holloway, Stephen P. Rice, and Gill Valentine, eds. (2003). Key Concepts in Geography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

x. In the interest of full disclosure, I cannot back up this assertion with a specific citation, so you should regard it with caution. I saw it in an ad for McGraw-Hill in the wave of publisher consolidations sometime back in the late 1990s. The actual figure is far higher today, and of course its meaning has been transformed by the destruction of the "page" as a unit of textual, literary, or productive measurement. As of May, 2008, every day, 1.6 million blog posts appear online. (Technorati data, cited in Ben Schott (2008). "Minute Waltz." New York Times, May 16, Op-Ed Page, p. A23. The International Data Corporation projects that the total supply of digital storage in 2010 will be ten times the figure it was in 2006. John Schwartz (2008). "In Storing 1's and 0's, the Question is $." New York Times, April 9, Tech Innovation Special Section, H1, H6, quote from p. H1. "But the downside is that much of this data is ephemeral, and society is headed toward a kind of digital Alzheimer's. What's on those old floppies stuck in a desk drawer? Can anything be read off that ancient mainframe's tape drive? Will today's hard disk be tomorrow's white elephant?" (quotes from p. H1).

"For many young scholars, the major hurdle ... is getting started. Many desist from submitting a paper for publication because of a lack of confidence in the quality of their own work, or out of a fear of being rejected for reasons that were not anticipated, or out of a broader fear of the unknown. My first recommendation is to overlook these concerns. Get in the habit of writing and preparing articles for publication -- but only submit those articles that are carefully crafted and based on solid analyses and thoughtful research." Larry S. Bourne (1989). "On Writing and Publishing in Human Geography: Some Personal Reflections." In Martin Kenzer, ed., On Becoming a Professional Geographer. New York: Merrill Publishing, 100-112, quote from p. 101. Reprinted by the Blackburn Press (Caldwell, NJ), 2000.

Almost finished with a very rough first draft of Radical City, March 2008 (Elvin Wyly)

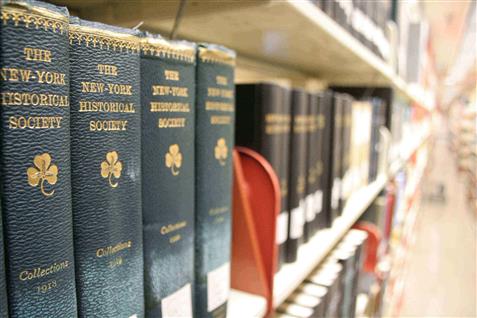

Knight Library, University of Oregon, February 2008 (Elvin Wyly)

"Several years ago I began to teach a seminar on writing ... As the first chapter explains, I found myself giving private lessons and therapy to so many people that it seemed economical to deal with them all at once. The experience was so interesting, and the need for something like that class so obvious, that I wrote a paper (the present first chapter) describing it. I sent the paper to a few people, mostly students who had taken the class and some friends. They, and others who eventually read it, suggested other topics that could profitably be covered, so I kept on writing."

"I had expected that helpful response from friends and colleagues ... but not the mail that began to arrive, from all over the country, from people I didn't know, who had gotten the paper from a friend and found it useful. Some of the letters were very emotional. The authors said that they had been having great trouble writing and that just reading the paper had given them the confidence to try again. Sometimes they wondered how someone who didn't know them could describe their fears and worries in such precise detail." Howard S. Becker (1986). Writing for Social Scientists: How to Start and Finish Your Thesis, Book or Article. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. vii-viii.

"James H. Billington, the Librarian of Congress, drew laughs when he expressed concern about what he called 'the slow destruction of the basic unit of human thought, the sentence,'" because so many students "are doing most of their writing in disjointed prose composed in Internet chat rooms or in cellphone text messages."'

"'The sentence is the biggest casualty,' Mr. Billington said. 'To what extent is students' writing getting clearer? Is that still being taught?'" Quoted in Sam Dillon (2008). "In Test, Few Students are Proficient Writers." New York Times, April 3.

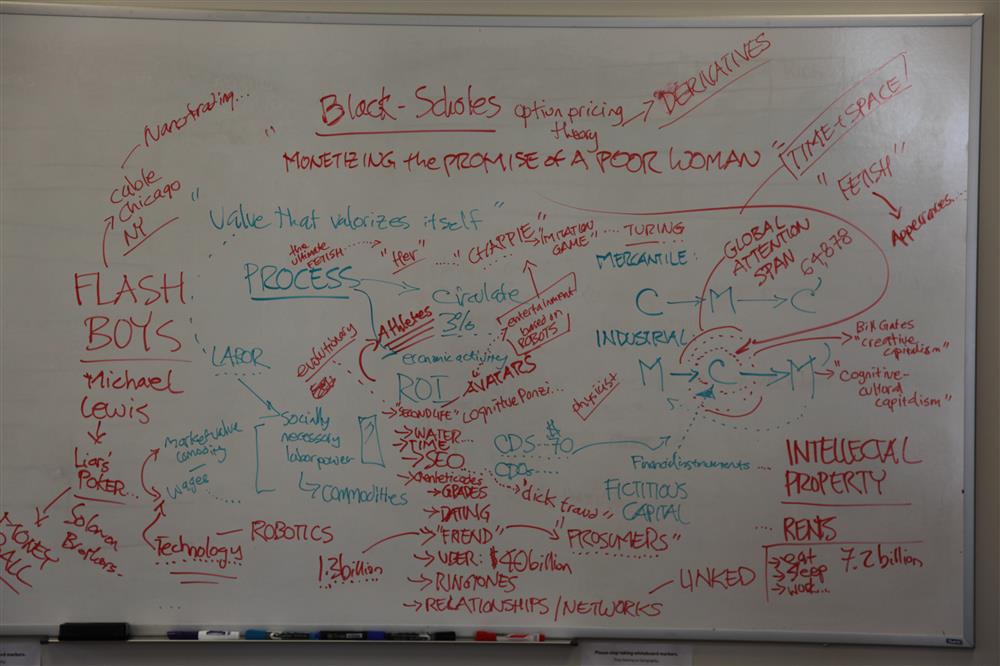

Trying to make sense of the model output, Vancouver, March, 2006. SAS runs the maximum-likelihood algorithm on millions of observations, and spits out the results so quickly. But what does it all mean? Answering this question cannot, and should not, be automated. It requires humanity, and usually a lot of time.

The essential elements are all there: great literature, old and new; a thick stack of newspaper clippings; primary sources, of a sort (in this case, a lawsuit), juicy multicolored pens, and ample pads of paper; draft manuscript evolving towards coherence; and, of course, a fresh hot mug of coffee. Vancouver, February 2008..

"...it was through this brutal and crude machine that classic works on revolutions and civil conflict were produced; the novels of Hemingway, Orwell, Steinbeck and Hunter S. Thompson—as well as the annual letter from your grandfather on your birthday. In the end, the typewriter defies everything our modern word processors and, if you want to go further, our postmodern world is today: artificial and fake. There is nothing romantic about Microsoft Word.

Our modern machines now blind us to how our words were once produced. Instead, our writing is now trapped within Frederick Taylor's theories of scientific management. We are now alienated from our craft—to use the Marxian definition."

My Keyboard is Completely Drenched.

Read These. If you're not in tears afterwards ... then maybe I should hire you as my lawer. Or my bodyguard. Or my assassin.

Jeremy Shepherd (2010). "Writer Works Despite Cancer Diagnosis." Vancouver Courier, October 1, D4-D6.

Tiffany Crawford (2010). "Historian Chuck Davis, Relentless Pursuing Facts about Vancouver, Authored 14 Books." The Vancouver Sun, November 22, A3.

"...the audience shapes the material. They are part of the process. I write, they edit." George Carlin and Tony Hendra (2009). Last Words. New York: The Free Press, p. 249.

"Baker is a classically trained musician who listens to trance and electronica, a retiring, mild-mannered person given to strong feelings and passionate obsessions. I gathered that there was a period not so long ago when he tended to get a little emotional at South Berwick town meetings when some locals wanted to tear down an old building and replace it with a new one. In 1999, during his "Double Fold" phase, he got so upset that the British Library was deaccessioning its collection of 19th-and early-20th-century American newspapers that he cashed in a large part of his retirement savings and bought them himself: five trailer-truck loads, 6,000 bound volumes and another thousand wrapped bundles, which he stored in an old mill building in nearby Rollinsford, N.H. The other tenants were the Humpty Dumpty Potato Chip Company, a French thermal underwear company and an outfit that collected old medical equipment -- gurneys, examination tables, and what Baker described as monster-movie X-ray machines." Charles McGrath (2011). "The Mad Scientist of Smut." New York Times, August 4.

JCCA™

Our present age of automated epistemology seems to be dominated by page-view statistics, twitter followers, ISI impact factors, and all sorts of other innovations of a digital capitalism that seeks to monitor and commodify every form of human communication. We should think carefully before we deploy our cyborg technologies to that most human of relations -- the bond between writer and reader.

For me, quantmag* that I am, the measure that matters is that of one point oh -- the one-on-one, personal word between reader and writer. Not long ago, my friend Jeff Crump sent me a very kind note on Positively Radical. Jeff wrote, "Finally had a little time to read your great paper 'positively radical.' It is one of the best I have read in a long time. If you look closely at the attached image, you will see that your paper is the 'cat's meow" around here." Jeff is being far too kind here -- on his worst days his work is 2.71828 times better than the stuff I do on my best days. But it's a privilege to be Jeff Crump and Cat Approved™!

Image ©2011 Jeff Crump, used by permission.

*Quantmag. The late great Frank Pucci, comrade from graduate school days, often complained about the atrocious writing of "quantitative maggots." I learned more from him than he realized, and before I ever found the time to tell him and thank him properly ... suddenly he was gone.

Put your foot down. It's time to make a stand and defend the footnote.

See

"Writing at Risk."

This was the title of a talk I gave at Walter Gage Residences at UBC not long ago. The students were engaged and brilliant, and they asked me challenging questions about many things. One of the things we discussed involved matters of integrity and trust. I had been ranting about technology and privatization, and the example I used was Turnitin.com, which has a lucrative contract with UBC. But I was also ranting about a lot of other things in that talk, so we didn't have enough time to explore some of the tricky issues involved in policing academic integrity.

The very next day, I read a nice essay by a graduating twefth-grader. I was struck by the thoughtful and articulate analysis. Linette Ho marshals the evidence to show that "The high expectations for young kids to do well is affecting their confidence and leading them to choose cheating as an option." Ho laments the pressure endured by students today, and thus she expresses the kind of sentiment I have -- a frustration with the acceralting hamster-wheel of competition (which is driven in part by technology, which itself enables accelerated cheating). But while Ho is an idealist like me, she is also much more pragmatic and and realistic. She opens her essay with a story of going into Grade 12 examinations, where "Out of the blue, I noticed in my peer's pencil case a small crumpled piece of paper with tiny scribbles all over it. It was the answer key." She admits to "mixed emotions of frustration and confusion" when she realized that cheating is so pervasive. Not everyone has as much integrity as she does.

The idealistic, humanist in Ho might support my personal refusal to use Turnitin.com. She would agree with me that using this service would be a clear statement to my students, "I do not trust you." But the realistic, pramatic Ho might be infuriated by my naivetee. By avoiding Turnitin.com, I am allowing an unknown number of students to take shortcuts or engage in outright fraud, and I'm not distinguishing these charlatans from those with true integrity. This seemed to be the logic of one of last night's brilliant students, who was genuinely confused and curious as to why I didn't use Turnitin.com. If it reduces the incidence of academic misconduct, what's the problem?

It's a fair question, and I've been giving it a bit of thought while working on other things today. I don't do wikis or facebook or twitter, but I do try to keep up with my share of that old early-twenty-first century set of technologies (email, a very simple web page). So if you are inclined to help me learn more about these issues, I'm grateful for anything you can teach me. I'm fascinated by all our changing relations of technology, writing, competition, expertise, and trust.

Read Linette Ho's valuable and reflective essay. I'll read anything with "Writing at Risk" that lands in my inbox. I won't be able to respond to you individuallly (in fact, UBC regulations don't allow me to collect any personally identifiable information, including your email address) but I do promise to read and think very seriously about everything received.

So, read and discuss: Linette Ho (2012). "Classroom Cheating on the Rise." The Vancouver Sun, March 28, p. A13.

[The rest of this page is just a random collection of rants on writing that I've accumulated responding to student emails over the years, and trying to formulate coherent reasons for pestering students to write, or explaining why I did certain things in classes, etc.]

[Note: this is not research. This information is provided only to encourage thought and discussion, and for quality improvement studies of teaching, student assessment, and student advising. This is not an undertaking intended to extend knowledge through a disciplined inquiry or systematic investigation. The purposes of this activity qualify for exemption from behavioural research ethics review under Article 2.5, 'Quality assurance and quality improvement studies,' and/or Article 2.6, 'Creative practice activities.']

CopyLeft 2017 Elvin K. Wyly

Except where otherwise noted, this site is

Write in whatever way works for you -- for your mind, your muse, your creativity and your rigor. But consider doing just a little bit by hand, on paper.

If (when) you have a technology problem, don't ever let that stop you writing. Always keep a pad of paper so you can take notes. Just in case you lose your notepad, ask for receipts as you make your way through the commercial landscape. That way, you'll always have tiny bits of paper you can scribble on when you get an idea. The lowly cash register receipt and the crumpled bar napkin might be pages in your next masterpiece.

Paper is that amazing invention that allowed humans to read and write. As readers and writers became social roles, individuals and societies had to make collective investments in the meanings of words and sentences. These collective investments required constant negotiation across difference, and thus came to define societal identity and function.

The work required to build a culture of literacy matters: it makes it possible for individuals to learn and communicate in very unusual ways. It allows people to discover new possibilities. The possibility of discovery itself, however, is a social creation: if not for those major collective investments in defining shared meanings, and if not for all the work required to teach ourselves about them, then we'd never make those discoveries. We'd never see the world in a different way, the way our imagination is fired after we've finished reading a Truly Great Book.

This kind of imagination is about two thousand years old. A series of clever innovations in China allowed new ways of reducing wood to pulp and then using bleach to create high-quality paper. As these innovations spread, then the imagination began to build on itself, almost in a chain reaction. New possibilities were imagined precisely because society was creating new ways of discovering, through the ongoing struggles to define new meanings. We understand more because we all worked together to learn what it means to understand.

The paper-based culture of literacy worked for a long time, and there were even periods of peaceful coexistence that allowed the publishing industry to negotiate a middle ground between capitalism and non-capitalist forms of knowledge.

Now that's changing, and fast.

The alternatives to paper are creating very differnet worlds. These worlds are coming into view faster and faster. But some of those worlds look pretty scary. And when our culture of literacy goes digital, everything changes in the rules about who gets to see what in the process of making and interpreting social meaning. The digital age is the hundred years' war over information, meaning, and human attention. It's not enough for you to know.

So maybe we shouldn't abandon paper just yet. Maybe paper still has a place in our digital worlds. In a digital world of aggressive commercialization, pen and paper passed back and forth -- written by one person on a piece of paper, and then read by another human being holding that piece of paper -- isn't big business. Compared to the rest of postindustrial society, it has become immune to commercialization. It provides a refuge, an escape, and a genuinely dialectical alternative.

The problem, of course, is always a matter of scale. If we only share things one-on-one with sheets of paper, we'll never be able to have the "reach" across geographies, and across social roles, that we have to live with today. That's why the argument is partial: do just a little bit by hand, to see where it takes you. Maybe just a few people read what you write by hand. But they're important to you, aren't they? And maybe your audience when you write is just one: you write something one day ... and some time later you come back to it. You've changed, so as you read those handwritten notes, you learn about who you were in the past. And while you're learning, nobody can advertise to you. Nobody can collect data on what you scribbled on that pad of paper. Unless you're a celebrity, people won't chase after you to see what you wrote. That allows you to imagine things in ways that are as pure as we can get these days.

So some think that paper still has a place, at least a small place, in our increasingly digital, commercial worlds.

Some of us still like to write on paper.

Here's one to learn from:

And Charles McGrath, it's a wonderful article. Next you should go talk with John Adams, David Listokin, Arlene Pashman, Liam McGuire...and some other students and mentors I'd like you to meet.

Now it's time for me to shut down Ye Olde HTML Editore and reach for my pen and my pad of paper!

"It's not writing that takes Caro so long but, rather, rewriting."

Not long ago, John McPhee recalled his experiences writing "Looking for a Ship," and his negotiations with the editor Robert Gottlieb at The New Yorker. McPhee had joined a merchant ship on a route that took him to Miami, Cartagena, Balboa, and several other ports, and eventually wrote a story of some sixty thousand words. Gottlieb was okay with every word but one, which "had come out of the mouth of a sailor named John Shephard, who said, 'It's a rough life. Rough life. Go ashore, you spend your money, get kicked in the tail. Plenty of friends till the money runs out. A seaman smells like a rose when he's got money, but when he has no money they say, 'Motherfucker, get another ship.'"

McPhee uses the story to open a delightful etymology of style, usage, and editing at The New Yorker over the past forty years. McPhee did his best to stay true to what sailor Shephard really said, and made the case to Gottlieb:

"He asked if I might think it advisable to reconsider the sailor's word."

"Shephard didn't reconsider it, I responded. How could I?"

So Gottlieb decided to do a bit of crowdsourced-editing, back in the days before the term had even been invented.

"Bob leaned over a bright-yellow four-inch Post-it pad and in big black letters wrote "MOTHERFUCKER" on it with a Magic Marker. He was wearing an open-collared long-sleeved shirt. He stuck the Post-it on the shirt pocket. He said he would call me again later in the day..."

"Off and on that day, Gottlieb walked the halls of the magazine wearing his "MOTHERFUCKER" Post-it as if it were a nametag at a convention. He looked in at office after office and loitered in various departments. He drew a blush here, a laugh there, startled looks, coughs, frowns. He gave writers moments of diversion from their writing. He gave editors moments to think of something other than writers. He visited just about everybody whose viewpoint he might abosorb without necessarily asking for an opinon. In the end, he called on me. He said The New Yorker was not for 'motherfucker.'"

John McPhee (2012). "The Writing Life: The Name of the Subject Shall Not be the Title." The New Yorker, July 2, 32-38, quotes from p. 32, 35.

Gonzo Writer's Pilgrimage

HST's seat at the Woody Creek Tavern, Woody Creek, Colorado, July 2012.

"A piece of advice that I ALWAYS repeat to myself that keeps me going that YOU gave to me was,'Good writers only write about one of two things -- things they love, and things they hate.' Writers block no more!"

An update from Melissa Fong, who thrived in our Urban Studies program a few years back, taught me so much more than I taught her, and went on to the Ph.D. program at the University of Toronto. Melissa and I were corresponding and commiserating over the terrible loss of Neil Smith, who inspired us both in so many ways.

[September 29, 2012]

"Even when an individual has been accepted as an author, we must still ask whether everything that he wrote, said, or left behind is part of his work. The problem is both theoretical and technical. When undertaking the publication of Nietzsche's works, for example, where should one stop? Everything that Nietsche himself published, certainly. And what about the rough drafts for his works? Obviously. The plans for his aphorisms? Yes. The deleted passages and the notes at the bottom of the page? Yes. What if, within a workbook filled with aphorisms, one finds a reference, the notation of a meeting or of an address, or a laundry list: is it a work, or not? Why not? And so on, ad infinitum. How can one define a work amid the millions of traces left by someone after his death? A theory of the work does not exist, and the empirical task of those who naively undertake the editing of works often suffers in the absence of such a theory."

Michel Foucault (1969). "What is an Author?" Lecture to the Société Français de philosophe, Paris, 22 February, in Paul Rabinow and Nicolas Rose, Eds., 2003, The Essential Foucault. New York: The New Press, 377-391, quote from p. 379

"When we write, a unique neural circuit is automatically activated," according to the psychologist Stanislas Dahaene; "There is a core recognition of the gesture in the written word, a sort of recognition by mental stimulation in your brain." Quoted in Maria Konnikova (2014). "What's Lost as Handwriting Fades." New York Times, June 2.

Writing

Aloud

Allowed

Writing, watching, listening, brainstorming in the media noösphere, and reflecting on the archives. To get the full effect, read Trevor Barnes' valuable "Taking the Pulse of the Dead," Don Mitchell's extended version of "Neil Smith, 1954-2012: Radical Geography, Marxist Geographer, Revolutionary Geographer," and my "Where is an Author?" (or the scribble archive of a preliminary version), and then enjoy Alex Gibney's amazing Gonzo documentary...

...and then this might make sense.

*

A Place of Mind and a Place of Sentence Fragments

"Dan Perrett (founding partner) said that UBC's presidential search is 'the most important search that Perrett Laver will undertake in the six months.'"

-- From an email from UBC's Chancellor, reassuring us all that the "internationally renowned search firm" Perrett-Laver will actually give us the time and attention we deserve. Perrett-Laver is headquartered in London, U.K., with offices in Vancouver, San Francisco, Chicago, and Washington, DC. This is the most important editing mistake I will be undertaking to understand in the [next] six minutes, given the flood of hasty emails that now define our digital lives. November 19, 2015.

"Well into the word-processing age he insisted on composing his stories on a manual Royal typewriter, which he said produced copy 'that has some relationship to my humanity'..." From the obituaries for the journalist Morley Safer, as reported in Victoria Ahearn and Lauren La Rose (2016). "Fellow Journalists Honor Safer." Vancouver Sun, May 20, p. NP6.

"This was a thing that had been happening to me lately. I had started to see myself as a mechanism through which signals were passed. I would be sitting on the bus, jotting down snatches of conversation in my notebook, details of scenery or sensation, and I would see myself as a primitive device, a machine for the recording and processing of information. I would be at the checkout in a cavernous Walmart, paying for snacks, and I would see myself as one of many millions of mechanisms in a vast and mysterious system for the upward transfer of wealth. I knew, of course, that this was a result of my overexposure to mechanistic ideas, but on some level I recognized that I had always seen myself in this way."

This quote comes from a brilliant, hilarious, and occasionally satirical portrait of the transhumanist Zoltan Istfan's campaign for the U.S. Presidency. See Mark O'Connell (2017). "600 Miles in a Coffin-Shaped Bus, Campaigning Against Death Itself." New York Times Magazine, February 9. O'Connell's words spoke to me, even as I recoiled at the idea of a human journalist, a human reporter portraying one's own humanity as "a primitive device," as a machine for the "recording and processing of information." I do quite often feel as one of many millions of mechanisms in a vast and mysterious system, a nice and crazy ecosystem for the upward transfer of wealth. But a primitive device, a machine? That I'm not so sure about -- either for O'Connell, for me, or for you, dear reader. Record a little bit of information, but when you "process" the information, pour some creativity and passion into the mix.

We are in a nice and crazy world. Always take a note-pad, wherever you go, and try to steal a few moments to write out ideas, interpretations, and provocations.

Nice and Crazy: Avinguda Diagonal, Barcelona, February 2017.

Writing on "Conspiracy Capital," March 17, 2017, tapas in Barcelona

"It's a one-on-one interaction that doesn't get interrupted by Twitter alerts."

These are the words of Doug Nichol, director of a 2017 documentary film, California Typewriter, featuring the actor Tom Hanks and musician John Mayer. Nichol's film portrays the resurgence of interest in typewriters as the result of "digital burnout" and people wanting a connection to the past. "In his film ... Nichol interviews Hanks, who said he uses a typewriter almost every day to send memos and letters. 'I hate getting email thank-yous from people,' Hanks says in the film. 'Now, if they take 70 seconds to type out something on a piece of paper and send to me, well, I'll keep that forever. I'll just delete that email.'" Russell Contreras (2017). "Typewriters Gain Fans Amid 'Digital Burnout.'" Associated Press / Vancouver Sun, June 20, p. C5.