Teaching

It's not about me, it's about you.

Every now and then, scholars who work as educators are asked to present their "teaching philosophy." For those working in so-called higher education, the exercise often involves careful introspection and an uncomfortable balance between understated modesty and the self-promotional imperative to document the elusive, ephemeral achievements of the classroom. It's hard to measure the surplus value created by teaching labor-power. Grants have dollar signs attached to them, and research yields books or articles that can be counted and monitored on such bizarre benchmarks as citations or the "impact factor" of the journal where the work appeared.

But success in teaching is much more difficult to measure and evaluate. Yes, of course everyone cites numerical scores on teaching evaluations. But it is widely understood that these measurements capture only one limited and particular type of success. Most students give positive evaluations for the educational experiences they enjoy; the learning challenges that have the greatest long-term value are not always enjoyable (at least not at first...).

So the eyewitnesses at the scene of the pedagocial crime are not always able to distinguish Good Teacher from Bad Teacher in the lineup. At the end of the semester, the eyewitnesses leave, and it's hard to track them down again. The successful "teachable moments" in the classroom, therefore, are elusive and ephemeral. So when it comes time for professors to justify ourselves, we're forced to be a bit self-promotional, and to try to find some tangible evidence of success.

Not long after I joined UBC, I went through that familiar keep-your-job ritual of the academy, The Tenure Review. In the process I tried to achieve the right balance between modesty and self-promotion in my statement of teaching philosophy. Here's what I wrote:

"For many years I have been privileged with the reduced teaching assignments that come with a joint appointment with a research center. I do not regard such a privilege as a license to neglect students. I really do believe the oft-recited statement that research and teaching are two sides of the same coin, although I would add the valuable currency of advising to the metaphor. In the realm of advising through scholarship, I undertook major substantive revisions and rewrites on two student seminar papers that showed promise (Keith Brown, Julie Silva), and stewarded the manuscripts to peer-reviewed publication. In formal classroom teaching, I am committed to rigor and innovation at all levels of the curriculum, and I have enjoyed teaching advanced seminars with enrollments below a dozen, middle-division offerings with 75-100 students, as well as introductory surveys enrolling 150 to 250. By the numbers, student evaluations usually rank my overall teaching effectiveness at a mean between 4.4 and 4.6 on a 5.0 scale. I am also working to revitalize our department's Urban Studies program. My first offering of the program's fourth-year seminar coincided with intense public debate around Vancouver's bid to host the 2010 Olympics, and thus one part of the class integrated urban studies scholarship with a local case study of the bid process. We worked with a local alliance of nonprofits and other researchers on campus to develop a community survey (for which we secured ethics/human-subjects approval) administered at a series of forums organized by the city's Mayor.

At the graduate level, I have enjoyed the opportunity to undertake major revisions to the structure, literature, and theoretical emphasis of long-established courses in the graduate curriculum (urban housing and labor markets, urban systems, migration). I also developed a new course at Rutgers, focusing on contemporary developments in quantitative geographical analysis; this course allowed students to develop the methodological components of their individualized research agendas while engaging classic multivariate techniques as well as recent advances in ecological inference, expansion methods, and spatial econometrics. Most of my advising roles have been as part of the 'supporting cast' of committees, but I do take these responsibilities (and opportunities) very seriously. I am currently supervising a new doctoral student at U.B.C. (Mona Atia) who is working with me on a project supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada."

On reflection, the precarious balancing act of modesty and self-promotion was a failure: I took far too much credit for a teaching enterprise that is (or at least should be) an inherently collective, social, and cooperative activity. Teaching is the ultimate public good: in Sayerian realist philosophy, "teaching" is part of a quintessentially necessary relation, with one facet defined by its corollary: teaching presumes learning. It's a cooperative project, even when (and perhaps especially when) instructors impose a rigid, hierarchical order in the classroom. Yes, as an undergraduate, I did enjoy those courses where the instructor seemed casual and open to students' requests and recommendations on the content, schedule, and workload of the semester; I understood clearly that those instructors were giving students the opportunity to participate, partially to subvert the traditional teacher/student hierarchy. Yet I also enjoyed those "traditional," hierarchical faculty, who imposed clear protocols and requirements that we were expected to follow. Even before I knew anything about Chomsky, I vaguely understood that one of the functions of the academy is to manufacture consent -- and if we are involved in that, then we might as well try to reserve our consent for those who deserve it. I was all too happy to consent to a hierarchical learning experience in a logical, rigorous curriculum taught by first-rate scholars. Such collective consent can make the hierarchical classroom setting just as cooperative, a common production, as the laid-back, open-ended participatory seminar or workshop. But that hierarchy is dangerous when it is generalized to the entire curriculum: only a few parts of a few fields can legitimately stake a claim to a settled, established paradigm where there really is One Right Way to get The Right Answer. And those fields, and those claims of One Right Way, are often precisely the settled assumption we most need to disturb, to unsettle; it's just that we need to invest enough time in that traditional hierarchical classroom to understand the body of knowledge that we'll need to dismantle, decolonize, and reconstruct.

As with all other public goods, higher education is under assault. There are enormous profits to be made by re-defining the collective teaching/learning experience, to shatter the community production into individualized elements that can be standardized, routinized, commodified, and put under surveillance in the expanding audit cultures of neoliberalism. The push for privatization and marketization has been underway for some time, and in many universities it is now standard procedure to view students as customers. Did you enjoy the class? What did you like most about the class? What did you like least about the class? This insidious trend is perfect for socializing generations of students into life in the consumer society, where everything has its price. It's also in line with the established infrastructure of treating consumers as targets: the next time you feel that warm glow of self-esteem when you are asked if you enjoyed a particular class, think about the last time an unscrupulous corporation suckered you into a nasty financial transaction, all the while advertising/assuring you about their commitment to customer service, and that "your opinion is important to us." And don't forget that the corporate model of targeting consumers is now diffusing throughout the university, enabled by the simultaneous and interdependent acceleration of a) competition, b) automation, and c) cynicism. Frank Furedi (2011, p. A12), Professor of Sociology at the University of Kent, relates a story that makes the point:

"A couple of years ago, I was listening to a presentation about a new and apparently sophisticated anti-plagiarism tool. Throughout the talk, the speaker boasted of her software's potential for detecting copied work and preserving 'academic integrity.'

I was a little despondent about the notion that, henceforth, the value of academic integrity would be secured through computer software. Nor did I feel reassured when, towards the end of the presentation, we were told that 'academic judgment' was still necessary to determine whether plagiarism had taken place. To me, the notion that academic judgment had become an adjunct to plagiarism detection software was even more disturbing than the association of this product with the upholding of academic security."

Even if we accept the logic of marketization, it is clear that the "product" of higher education -- the cooperative teaching/learning experience now subject to commodification -- is in crisis. In December, 2010, Maclean's surveyed the wreckage of the job market for today's new university graduates, compared to the Baby Boomers, Generation Xers, and members of Generation Y; Maclean's offered a depressing label for today's graduates: "Generation Screwed." Idealistic young students have always been faced with tough choices in how to balance the joy of pure learning with the pragmatic considerations of employment, debt, and long-term earnings potential; but things seem to have changed. Selling out doesn't work when there are no buyers for the commodity of higher-educated labor power; we need an entirely new labor theory of value. James Cote, a professor of sociology at the University of Western Ontario, notes that the university degree has become the "entry-level qualification" for a basic, living-wage job; the downgrading of labor now means that "Yes, there is an advantage to a university education. But only because there is a disadvantage" to other paths, other choices that were once viable points of entry into the middle class (quoted in Laucus, 2011b). Interviewed (Laucius, 2011a, p. C2) for a story on the catastrophe of high unemployment among recent graduates, business student Lauren Jamieson, 21, clearly understood the importance of product placement in a commodifed society:

"When my dad graduated, not that many people had university degrees. ... Now so many people have degrees. It's like, 'What else do you have?' It's like when you see two products on the shelf, and one has all these high ratings, and the other one doesn't."

You are Not a Product on the Shelf

You are not a product on a shelf. But if we don't act fast, you will be a product, with all the metaphors implied by what it means to be a product. If you're a product, then the question becomes: what's your price? Can the customer return you? What happens when the next best product comes along? What's your "sell by" date? In other words, what is your shelf life? The treatment of students as commodities is not far off, when the Financial Times quotes Dave Wilson, chief executive of the Graduate Management Admission Council in the UK, declaring that "places on exceptional MBA programmes are scarce commodities and the economic return is so substantial that some people are prepared to risk and to try things that would gain them an unfair advantage." (Wylie, 2012). If those admissions "places" are scarce commodities, and if too many people are competing for economic motivations to get that substantial economic return, then it makes it impossible for real, live human beings to decide whether to trust one another. We're all forced to see one another in instrumental terms, as commodities.

The solution? Hey, let's use a website to automate the process! Authenticate! Automate! Commodify! Now, when you're forced to go to services like this, you become part of the millions and billions of data points that ... make the corporate service-provider a "scarce commodity," extracting its substantial economic return. Dear Mister Dave Wilson also tells the reporter (Wylie, 2012) that the Council has "invested heavily in biometric palm-vein technology to defeat applicants who try to cheat its Graduate Management Admission Test."

As the comedian Dave Barry always wrote, I Am Not Making This Up. Consider a recent post to the UBC thread on Reddit. A user asks, "Will UBC start monitoring online assignment and online timed assignments/tests with video/audio feeds?" I remember first reading about these technologies more than a few years ago. They can use cameras on drones, facial recognition software and video authentication systems, and software to analyze the rhythms of the keystrokes you use to make sure that You Are Who You Say You Are. "Some American universities now monitor these kinds of things with film and/or audio software," the user asks on Reddit UBC.

"Lots of people do online assignments and tests in pajamas or with their kids around or breastfeeding, or while singing off-key, or in public, or with copyrighted material playing (like TV or radio) or whatever, and it raises all sorts of legal and privacy concerns and just seems creepy and it's a way to be totally disrespecting students so I hope UBC never adopts these things but do you think they will because it's relatively easy for TAs and profs to tell if online assignments are in line with a student's inclass and exam work and stuff based on syntax and grammar and stuff so it's super lazy to boot and a totally unnecessary invasion of privacy. Plus they don't watch you while you do regular at-home assignments. (Or are they secretly already doing so? /s) (also no I don't do assignments in run-on sentences but this is the web so yeah)."

You remember the cliche, right? You're not paranoid if they're really out to get you. This is a student who has given some serious thought to the implications of technological possibilities. A lot of those implications are simply logical, if extreme, extrapolations. And, to judge by the comments of those who read and responded, there's quite a bit of fear ... and humor or irony. "Well, we are discussing having each student implanted with a monitoring chip," one writes. "Welcome to Imagine Day," another posts. "Please give me both your arms."

Then things go in another direction. "If we are talking about actual tests worth a large fraction of the course grade then sure, monitoring sounds reasonable because it's like the same thing as going to write the exam."

Huh? You mean unlimited surveillance is okay, just so long as it's for the big things that really count in the grade? Think through the implications of that logic (I can't tell you what to think, I can only begin a conversation about how to think).

A few other students offer unrelated comments, and then someone else writes this: "It's part of a deal the American universities cut with the FBI. Now they can blatantly spy on you with no repercussions or outcry. Be warned, you're now on their watch list."

This might be the next Glenn Greenwald, who helped document the details of the NSA's comprehensive online surveillance of hundreds of millions. But this ain't just the FBI anymore! Whatever nation you're living in, and whatever nation you were born in or have some ties to ... they're all having to keep an eye on the population, because that's what defines the nation-state: a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. As more of life goes online, so does the state -- police, military, security. Every country has a different phrase.

At this point, I am about to cry. Students are out there thinking deeply about how much surveillance UBC is using on them. Whatever time they're devoting to these thoughts comes from something else: there's only so much time in the day. Isn't it sad that the relations between students the institution where they are coming to learn comes down to ... wondering what kind of technology is going to be used by the "university" on its "students"?

*

Teaching requires trust. Learning requires trust. Trust cannot be automated, despite all the sophisticated bots and Cloud services, and all the neocommunitarian, neoauthoritarian efforts of Corporate Capitalism and the iNSA American Cybersecurity Infrastructure to develop a "National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace."

Yes, yes, I know. Five minutes from now, they will assure us that trust can be automated, digitized, turned into a commodity.

But I don't think we should try. Trust must not be automated. We should actively resist efforts to automate trust. I want you to join me in this fight.

Why?

Not long ago, I finished reading the latest stack of final papers from a fourth-year undergraduate seminar that I teach every spring. This year, I gave the students more freedom than ever before; and the students responded with energy, enthusiasm, creativity, rigour, and integrity. That last point -- integrity -- is crucially important for the point I'm making here. My judgment of their integrity is not based on any technology: unlike some professors in some departments at some institutions of higher education, I do not require my students to submit their written work to services like Turnitin.com, which boasts more than 20 million "licensed students" that it can put through the automated pee-in-the-cup insult of comparing to its monstrous database of "220+million archived student papers, 90,000 journals, articles, and books, 1+million active instructors, 20+ billion web pages crawled, 10,000 educational institutions ... in 126 countries." (iParadigms, LLC, 2012). I know that hese numbers will change the second I finish writing this and posting it with my version of Ye Olde HTML Editor.

Don't let the details distract you. What matters is that a private company is growing dramatically each year, based on a convenient service provided to ... instructors who suspect that their students are taking shortcuts and committing plagiariasm. The instructors suspect their students because the competitive pressures are intensifying, and getting a college degree is now not enough. You have to get the right degree, with the best grades, and you have to have all the additional "extracurricular activities" that are no longer "extra," because everyone now expects those extras... and on and on, one and one, and soon the individual one of your individual identity bleeds into the binary code of a sentient global capitalism in its last gasp of the iAnnihilation of Space by FaceTime,® on Facebook.™ Now, only now, do I fully understand why Marcus Doel (2001) was so angry at The Number One.

Let me be clear: I do have respect for those students who see this kind of technological solution as a good thing. Some students have reminded me that these technologies will help ensure that the grade they get will not be undermined by the cheating of others who might cheat.

But I hope you can see what's at stake. Let's return to that stack of papers I just finished grading. I used the word "integrity," among many other words, to describe the impressive work of the students in that seminar. I trusted them -- I gave them a lot of freedom to explore through the term, without all the surveillance infrastructure of university life, which of course is inherited from the peculiar history of late-medieval European theology and nineteenth-century state-building in North America and other parts of what we recognize as the Global North. In other words, in that seminar I offered the option for students to get feedback on their ideas and their writing during the semester -- but I did not constantly interrupt them with midterm exams, quizzes, discrete chunks of thoughts that could be assigned grades to provide reassurance of progress (like "problem statement," "research design," "literature review," and the other modules I've asked in previous years). Instead, I allowed students the freedom to explore, while providing feedback on anything they put in front of me.

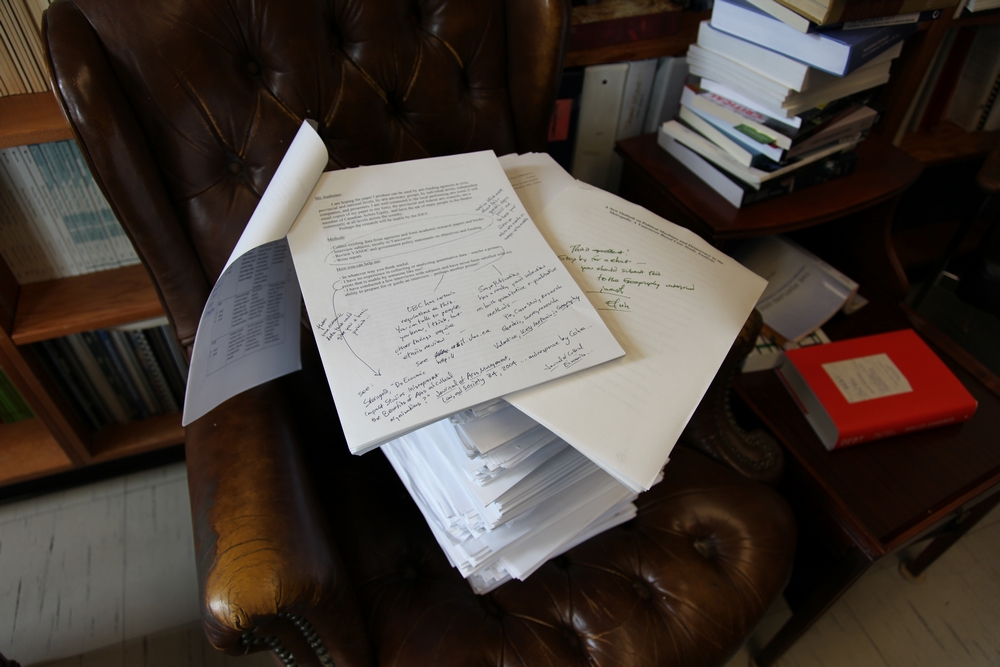

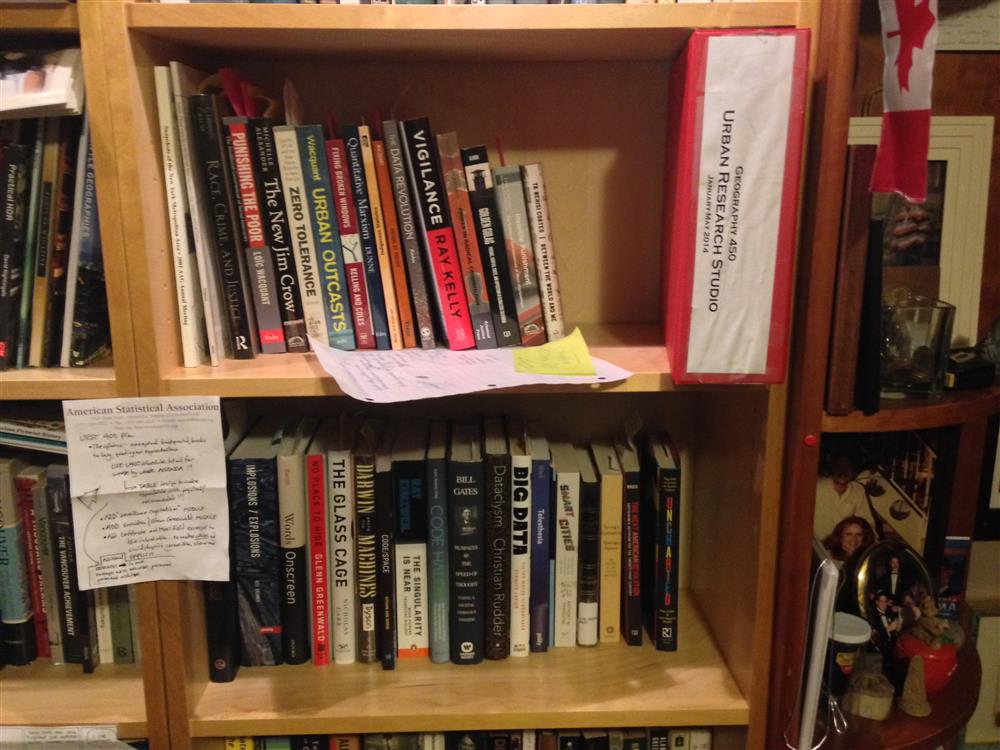

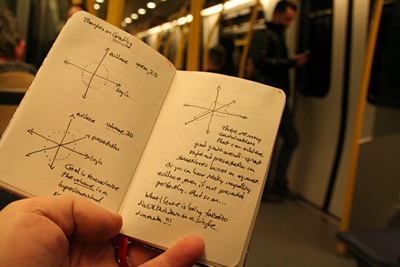

Here is a stack of papers from previous years. Note all the scrawled comments on the pages on top. That's what I did instead of all those mechanisms of grading and surveillance.

Other Teaching Resources

Students should note that I have rigorous expectations on sources and citations for all written materials submitted in my classes. I am also, however, an incurable optimist and a trusting soul. This means that I directly ask students to avoid plagiarism -- and I do not follow the innocent-until-proven guilty model of contemporary technological bureaucracy. UBC and many other institutions of higher education now subscribe to TurnitIn.com, a corporation that scans essays and term papers to check for material that may have been copied from web sites, published works, or previously submitted essays.

Please do not crush my naive, childlike idealism: one case of plagiarism will be all it takes for me to look like a total fool. In our instantaneous social-networked world, plagiarism can be detected instantly, and it would go viral. Reporters and satellite trucks would camp out outside my office, and I'd have my fifteen minutes of fame as the deer-in-the-headlights professor who was so naive, so trusting, to have been the last holdout. "He refuses to use plagiarism detection software! Ha! Everyone uses plagiarism detection software! Why is he so stupid? He must be the last professor on the planet who doesn't use these innovations! Look at this idiot!" I'm sure they'd have me on Jerry Springer...

At that point I'd simply be forced to give in. I'd have no choice. I'd have to require everyone in my classes to endure the academic equivalent of border strip-searches and 'enhanced' interrogation techniques.

The guilty-until-proven-innocent presumptions of "plagiarism detection services" goes against every principle and passion of my heart, mind, and soul. So does the rampant privatization of academic culture: when a professor forces students to submit things to turnitin.com and related services, then those student essays become part of the ever-growing databases that the companies use in their sophisticated and aggressive marketing plans and business models. You can help me -- and other professors like me -- fight back by eliminating their market. Moreover, you should also note that I've built in sufficient provisions in my course polices -- such as the permission for revision and re-submission if you're not satisifed with a particular mark -- that allow you to avoid the high-stakes, life-or-death night-before-the-due date panic that might lead you to think about cutting and pasting or doing some other kind of plagiarism. Please, please, please do not plagiarize. Choose any recognized citation style, and use it consistently in your writing to provide information that will allow a reader to a) verify statements, assertions, or interpretations, b) locate further information about a particular topic, c) distinguish your analysis and interpretations from statements or information you've borrowed from other authors, and d) show the reader all the work you've done tracking down important sources and reading to learn about a particular issue. I do not count footnotes or endnotes in the stated word limits for assignments, and so it is always better to provide more citations rather than fewer. Consult the resources below for further guidance, and also take a look at these general guidelines.

- University of British Columbia Libraries. 2006. "Avoiding Plagiarism." Online resource guide, last accessed June 27. Vancouver: University of British Columbia.

- Christopher R. Friedrichs. 2000. "Footnotes: A Guide for the Perplexed." Vancouver: University of British Columbia, Department of History.

- Kate Turabian. 1996. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. Sixth Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Adapted and Excerpted, University of Georgia Libraries.

If you are having difficulty getting started on your writing project, you may wish to consider some of my advice here.

"Eighty percent of success is showing up." Allen Stewart Konigsberg (Woody Allen), quoted in Thomas J. Peters and Robert H. Waterman, Among Friends (1982), reproduced in Una McGovern, ed. (2005). Webster's New World Dictionary of Quotations. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, p. 12.

Something to Aim For

I don't measure up to this standard, but the quote below does inspire me to try to keep up with the 'information explosion' and the dramatic, accelerating innovation of scholarship on cities and urban life:

"At the level of the university, teaching is itself an expression of scholarship. In an age of intense specialisation generating an information explosion, the scholar who can take information and synthesise it into coherent structures of knowledge is performing an essential and sophisticated task. To be able to create an intelligible and intelligent university course is a very significant accomplishment. The facile distinction between teachers and researchers comes from another era when a graduate education conferred upon the teacher a long-lasting competence in a single field. Today disciplines interpenetrate to such a degree that the researcher cannot rest tranquilly secure in his or her area of expertise, and the teacher cannot rest secure that a gentle summer's preparation will be sufficient scholarship for a good introductory course." -- University Senate (2002), Excerpt, "The Description of Criteria for Tenure and Promotion," Section A.1, Appendix to the Senate Executive Report on Revisions to the Tenure and Promotions Criteria and Procedures, March 21. Toronto: York University Senate.

Las Vegas, NV, June 2006 (Elvin Wyly)

Selected Previous Courses

Critical Measures of Urban Inequalities

(Graduate Seminar, Geography 552)

The New Spatial Politics of Social Data

A guest lecture for Geography 345, Derek Gregory's Geographic Thought and Practice, first written on November 2, 2004 and subsequently revised a bit.

Charting and Challenging Urban Hierarchies

(Graduate Seminar, Geography 531)

Research Proposal Seminar

(Graduate Seminar, Spring 2002, Rutgers University)

- Syllabus

- 'You are Here'

- Problem Statement

- Bibliography

- Preliminary Research Design

- Literature Review

- Methodological Statement

Quantitative Geographical Analysis

(Graduate Seminar, Spring 2001, Rutgers University)

- Syllabus

- A Short History of Quantification in Geography

- Data

- Classification and Cluster Analysis

- Principal Components Analysis

November, 2007 note: Oops. I should not have used standardized

data for the geometric illustration. Theta is always 45 when the

variances are equal. As Homer would say, D'Oh! See this instead.

- Logistic Regression

- Ecological Inference, Part 1, Part 2

Malmö, Sweden, September 2009 (Elvin Wyly)

Chicago, IL, March 2009 (Elvin Wyly)

Philadelphia, PA, June 2009 (Elvin Wyly)

"Stevens has a reverence for facts." Jeffrey Toobin (2010). "After Stevens: What Will the Supreme Court be Like Without its Liberal Leader?" The New Yorker, March 22.

Facebook or bookface?

Yes, we're all living in that high-tech, digital network society, but don't forget that old-fashioned, low-tech approach called The Conversation. Face-time, not Facebook. MyFace, not MySpace. Please don't be bitter that you can't follow me on Twitter, that "global clearinghouse for cerebral flatulence." [Joseph Brean (2010). "Taking Offended to a Whole New Level." National Post, December 28, A1, A6, quote from p. A1.] Unless I'm frantically preparing for class or I have another crash deadline, I'm more than happy to talk if you stop by unannounced. If I'm not there, then try me at one of these numbers: 778 899 7906, or 604 682 1750, or 604 822 4653. If you have to leave a message, do so on the first number only -- it's the one I know how to to check remotely.

Use email when it's the only viable option. But for most circumstances, the last remaining reason for our existence as human beings in this post-human age of Automated iEverything is ... the art of human conversation. Let's talk. If your dictionary defines "talk" as "email," then I respect that, and I do answer every email received from a human being. But the mathematical constraints are such that I can no longer predict how long a response will take. The floodwaters have risen too high.

So send an email if that's the only viable option -- for example, if you're far away and we're in different social-spatial worlds, not likely to see each other at the Geography Building in the next few days. Otherwise, if at all possible, try non-email forms of communication first: stop by my office, pull me aside if you see me in the hallway, look for me on the 99 B-Line down Broadway, or call me on the phone. Talk to me...!

"Libraries make citizens of us all."

Yes, yes, of course, use your high-speed-wi-fi-ipod-ipad-Blackberry-whatever-new-daintsy-craintz-modulated-bifribulation-fancy-device-comes-out-tomorrow to your heart's content. And while you're doing so, you'll be feeding into the giant datastream of a digital capitalism incessantly seeking to colonize every bit of your attention span to maximize profits.

If you really want to be revolutionary -- or even if you just want to spend a little bit of time now and then off the grid, beyond the tireless surveillance systems of transnational corporate capital -- then walk into a public library. Walk down an aisle. Choose a book, and another, and still another -- all without having been prompted by some software bot that claims (often with chilling accuracy) to know what you'll like based on your past behavior. Maximize the likelihood that you will defy their maximum-likelihood prediction models. Be an insurgent. Go to a library. Consider one of these irresistible libraries.

So you're bored studying geography at university. You've always got options. Drop out of geography and drop out of university, and ... pursue a military career. Become a junior officer, and seize power in a bloodless coup. Build your power around a mercurial cult of personality and style your image as a "desert nomad philosopher." Write a three-volume text for required reading in every school, outlining a "third universal theory" to transcend the contest between capitalism and socialism. Sponsor a cornocopia of terrorist organizations, and plan the bombing of an airliner that kills 270. Declare yourself "history, resistance, liberty, glory, revolution," and enjoy 42 years of absolute power. Revel in the wealth and authority until a civil war spreads, and until a U.S. Predator drone launched from Sicily and piloted remotely by satellite from a base outside Las Vegas strikes a direct hit on your escape convoy. Run from the devastated vehicles to hide in a concrete drainage pipe, only to get caught by a team of rebel fighters. Die at age 69 only three kilometers from your home town.

From information reported on Muammar Gaddafi, in Ben Farmer (2011). "The Last Hours of a Tyrant." National Post, October 21, A1, A2.

CopyLeft 2017 Elvin K. Wyly

Except where otherwise noted, this site is

Radical Pedagogy: Random Rants™®

Mensa Mentors

Tidbits from friends, colleagues, and students who've taught me

The End of Civilization?

"When I was in my final year of undergraduate studies, I remember striking up a conversation with a hungover student after one of Run DMSmith's Monday morning lectures. It was a miracle that the hungover student had made it to class. He asked if I wanted to grab a cup of coffee, and I said I had to run a few errands, but I could meet him outside the library in an hour or two.

He said: 'The library ... where's that?'

We are no longer in touch..."

--Tom Slater, February 2012

Look around this website first to see if I've already provided answers to some commonly asked questions. If you're looking for course materials, then see this for Urban Studies 200/Geography 250, this for Geography 350, this for Geography 450, and this for Urban Studies 400. If you're facing a deadline and you need an extension, or if you took a standing deferred and you're wondering what you need to do to finish the uncompleted work, then read this first. If you're working on a project for one of my courses and you have questions about formats, references, and the like, then take a look at this. If you're having trouble getting started with writing, then you may be interested in some of these reflections and bits of advice. If you need a letter of recommendation, I will try my best -- I cannot guarantee, but I will try -- and you can save us some back-and-forth email time by first taking a look at this.

Office Hours at the Alibi Room

May, 2012

"These are academic steroids."

--Anonymous high school senior in Connecticut, referring to the epidemic of students using ADHD prescription drugs to deal with the intensifying competition for good grades to earn admission slots at the top universities in the United States.

Global Gaokao

This is now a thoroughly transnationalized process of de-humanized competition, commodification, and stress. "[D]ebate appears to have grown heated lately over the value of gaokao," I read in a Times story about China's college entrance examination that "is generally considered the single most important test any Chinese citizen can take..." (Wong, 2012, p. A4). The high-stakes, make-or-break-your-life test "leads to enormous psychological strain on students, especially in their final year of high school." (Wong, 2012, p. A4). As the annual exam season reached a peak in the spring of 2012 for 9.15 million students across China, a Hunan Province talk-show host did a segment attacking the vast nationwide gaokao infrastructure that demands a kind of intense "rote learning" that "is endemic to education in China and that hobbles creativity"; the segment "gained popularity on the Web and became a focal point for fury against the gaokao in particular and the Chinese education system in general. Also widespread on the internet were photographs taken in a Hubei Province classroom of students hooked up to intravenous drips of amino acids while cramming." (Wong, 2012, p. A4).

Read that again. Students are hooked up to intravenous drips of amino acids to prepare for an examination. And by no means is this solely a story about China. There is now a massive, thriving market for the off-label use of ADHD drugs as academic steroids in universities and high schools across the United States and Canada. This is not learning. This is not education. This is not healthy.

Let me say that again. This Is Not Healthy.

Or let me go further, and try to use the tiddly-winks distractions of this medium of communication to break through our overwhelmed ADHD world to make the point more clearly:

this

is

evil

David Brooks quote:

"The most important and paradoxical fact shaping the future of online learning is this: A brain is not a computer. We are not blank hard drives waiting to be filled with data. People learn from people they love and remember the things that arouse emotion. If you think about how learning actually happens, you can discern many different processes. There is absorbing information. There is reflecting upon information as you reread it and think about it. There is scrambling information as you test it in discussion or try to mesh it with contradictory information. Finally there is synthesis, as you try to organize what you have learned into an argument or a paper.

Online education mostly helps students with Step 1. As Richard A. DeMillo of Georgia Tech has argued, it turns transmitting knowledge into a commodity that is cheap and globally available. But it also compels colleges to focus on the rest of the learning process, which is where the real value lies. In an online world, colleges have to think hard about how they are going to take communication, which comes over the Web, and turn it into learning, which is a complex social and emotional process."

Brooks (2012)

[still in progress, more to come later when I find the time...]

References

Brooks, David (2012). "The Campus Tsunami." The New York Times, May 3.

Furedi, Frank (2011). "Our Job is to Judge." Canadian Association of University Teachers Bulletin, 58(5), p. A12, A7.

iParadigms, LLC (2012). "Turnitin.com: About Us." Accessed at http://www.turnitin.com/en_us/about-us/our-company, May 3.

Laucius, Joanne (2011a). "Downwardly Mobile." The Vancouver Sun, June 11, p C1, C2.

Laucius, Joanne (2011b). "The Devaluation of Higher Learning." The Vancouver Sun, June 11, p. C2.

Lanier, Jaron (2010). You Are Not A Gadget: A Manifesto. New York: Knopf.

Wong, Edward (2012). "Test that can Determine the Course of Life in China gets a Close Examination." New York Times, July 1, p. A4, A9.

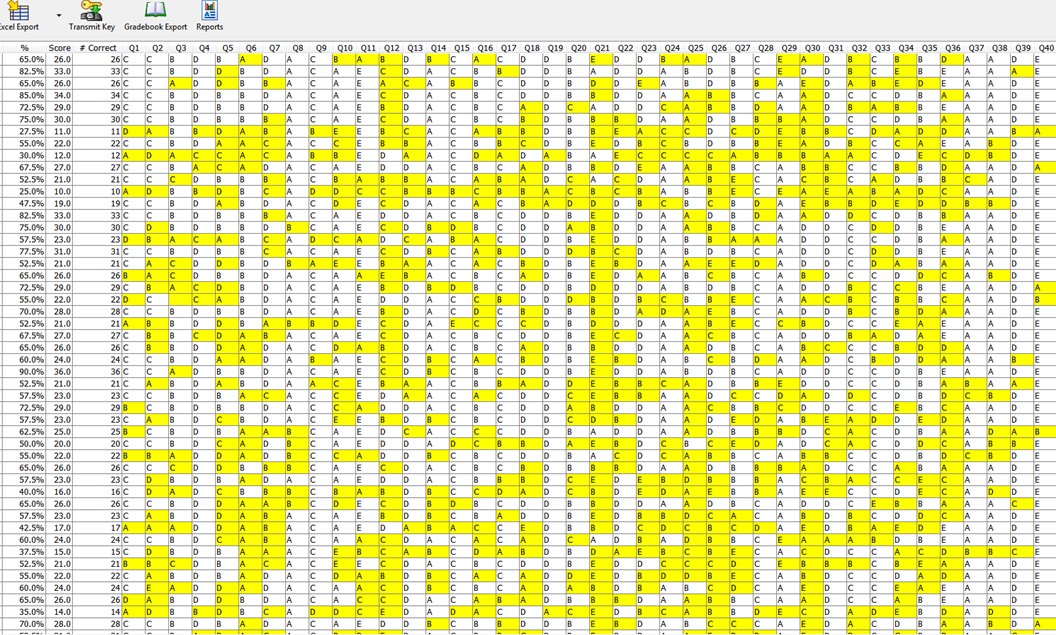

Draw your own inferences and conclusions from this image. But here's what comes to mind for me. There's a huge stack of papers sitting there in my office, each with comments and reactions scrawled across the pages. That means that there's a huge stack of papers that were never picked up by students. While a course is in session, a professor is indundated with requests for "feedback." That word seems to be redefined, however, once the final course marks are submitted. For many students, it's been a purely transactional affair all along: am I doing what's required to get the course grade I need? Once the final marks are submitted, then it's on to the next course, the next busy schedule of deadlines and expectations. There seems to be no time left for what the professor really thinks about a student's hard work -- all the multiple dimensions and subtle nuances beyond that cold, hard calculus of a single numerical grade. And there's even less time for students to respond to those thoughts, to revise, to clarify, to explain in a revised paper, no, you misunderstood me the first time around, this is what I really meant to say...

Scholarship is a conversation. At its best, it's a conversation that teaches everyone in ways that transcend orthodox hierarchies. Professors need to learn from students. That's why I see no wasted effort in that big stack of papers. All the scribbled comments and questions reflect the engagements of reading and learning -- me learning from the students' inspired creativity and hard work invested in the craft of writing. I do wish the students had stopped by to pick up the comments, but even so, I learned a great deal from their papers.

I know what you're thinking about that image above: Oh, how quaint, it's a stack of ... paper...

Let me offer three humble excuses. First, I beg you, please don't excommunicate me on the basis of my carbon footprint violations. Have you done the precise calculation on the carbon impacts of the device du jour you're using to read these words, or for that matter the beast I'm using to edit this little aitch tee em el file? (I've tried a few scenarios, and the results are not quite as utopian for the 'paperless' world as we might be led to believe by the technovangelists.) Second, it is not always accurate to presume that students would have been much more interested in detailed feedback if only everything had been done online. The online world is not without its own complications. When I look at that stack of papers, I see the results of students' work and creativity. Equally important is what I don't see: thousands of spam messages in between the paper submissions; lots of stressed-out late-night panics when the University's latest learning management system submission function goes haywire because of some server failure; dozens of back-and-forth emails because my computer can't read what your newer-faster-sexier gadget has produced; and so on and so on. The devil is in the details, as the saying goes, and we have had many centuries now to work out those devilish details in the medium of paper. Let's not throw it all away just yet as we become entranced by the digital temptations of speed and ephemerality. McLuhan's famous one-liner -- "the medium is the message" -- was more of a critical warning than a promotional ad for what Jaron Lanier (2010) calls "cybernetic totalism." (Besides, a workable compromise finally became possible when I spent a rather significant chunk of a paycheck to buy a scanner that can do a reasonably fast scan-to-pdf.

Third, there is the matter of time and space. No, I'm not thinking of the grand simplicity of a neo-Kantian world, safely dividing all of existence into time (for the historians) and space (for the geographers). I'm thinking of the speed of change of the tangible expression of human ideas, and the way these expressions can circulate -- in ways that free them from the constraints of time-space, but also rip them out of context. Context, after all, is defined by the confines of time and space. What this means is that digital copies are nice and convenient, but they must never be mistaken for the historical-geographical enterprise of written scholarship. The written word is a means of communication that allows a reader to enter into a most profound form of communication with an author separated by time and space. Each further separation -- the fragmentation of writing in collaborations by email across distance and time, the shift from writing for print publication towards blogging and twittering and other fast-changing forms of communication -- transforms the relationships between authors and readers. To be sure, these transformations do offer some exciting new possibilities: flash mobs, Facebook activism, and twitter revolutions are erupting everywhere, it seems. But not all of the possibilities are positive. To be specific: if you submit a paper to me by email, then it is no longer a communication from you to me. It is a communication from you to a vast infrastructure of legal rules, regulations, and technological measurement and surveillance enterprises that stand between you and I. Remember that frightened student on Reddit asking about UBC's surveillance? I do not intend to scare you, and I promise that I am not a charter member of the tin-hat fringe. But have you read the 180-page user manual for UBC's contract with iParadigms, LLC, for Turnitin.com?

I have.

I will not confess all of my thoughts and reactions here in this cybor agora. If you really want to know a few of the details of what we think, read this.

But from your perspective, what matters for you is this: if you submit your paper to me in the old-fashioned method of paper used by scholars going back, say, half a millennium, we don't even need to think about how the information might be used by corporations, bureaucrats, or algorithms. After we read and think and decide, then we can decide whether we wish to share this scholarly communication to a broader audience.

When Your University Rises in the Rankings, It's Time for You To Get Worried:

"In 'A Nation of Wimps: The High Cost of Invasive Parenting,' ... Hara Estroff Marano argues that college rankings are ultimately to blame for what ails the American family. Her argument runs more or less as follows: High-powered parents worry that the economic opportunities for their children are shrinking. They see a degree from a top-tier school as one of the few ways to give their kids a jump on the competition. In order to secure this advantage, they will do pretty much anything, which means not just taking care of all the cooking and cleaning but also helping their children with math homework, hiring S.A.T. tutors, and, if necessary, suing their high school. Marano, an editor-at-large of Psychology Today, tells about a high school in Washington State that required students to write an eight-page paper and present a ten-minute oral report before graduating. When one senior got a failing grade on his project, his parents hired a lawyer."

Elizabeth Kolbert (2012). "Spoiled Rotten." The New Yorker, July 2, 76-79, quote from p. 78.

The importance of Being There

At its best, the teaching-learning experience can be like a good sunset. You can photograph it.* You can record it. But can you ever really capture the experience? You simply had to be there.

*I keep looking for a great English Bay sunset photograph I took years ago, showing a vast crowd of people gathering for the Celebration of Light. Oof, where is that image? Oh, well. Let's run with a few variations on the metaphor. At its best, a teaching-learning experience is like being part of a cheering crowd,catching a fleeting glimpse of a double-rainbow, savoring the vibrant joy and happiness of a crowded rainy night market in Hong Kong,taking in the breathtaking visage of global capitalism reflected in the financial district of Central, sensing five hundred years of history at Xuande, glancing out the window and seeing a moonrise, strolling along a beach to see the smooth copper nighttime glow of city lights, basking in the red-maple-leaf glow of Canada Day crowds, floating along a watery city's central highway, or joining a protest to ask urgent questions about the injustices of war and the rights to housing and home...

[Note the specific reference to the "teaching-learning experience": I would never claim that I can deliver a teaching performance as good as a nice sunset, or a cheering crowd, or a double-rainbow, or anything like that! It's about your own teaching-learning experience, which might happen in your reading in the library, or your conversations with friends, or ... I hope ... a book you read after recognizing the name or topic after I mentioned it in class...

Pills on the Bell Curve

With the best of intentions, parents, teachers, and doctors are creating a generation of medicated life. Bronwen Hruska (2012) vividly recalls the moment when her son's fourth-grade teacher said, "Just a little medication could really turn things around for Will." They did try the medication route, and it worked for a little while with some strange side effects, but now several years later he's off the pills. It turns out that in the fourth grade, Will had just been a typical fourth-grader going through the normal adjustments of trying to focus on school. But this is where pharma society is changing so fast -- redefining

"the idea of 'normal.' The Merriam-Webster definition, which reads in part 'of, relating to, or characterized by average intelligence or development,' includes a newly dirty word in educational circles. If normal means 'average,' then schools want no part of it. Exceptional and extraordinary, which are actually antonyms of normal, are what many schools expect from a typical student."

"These books have lives that have changed mine."

Read. Think. Discuss.

"UBC Representatives: Please return the graduation data to the people of BC. I’m really sorry that I plotted it. In my defence you trained me for way too many years to compulsively plot things. Will you forgive me? Funny looking data is much better than none at all, and people would rather get it from you than from me. Keep new data flowing all the time. This information affects people’s lives."

Reading

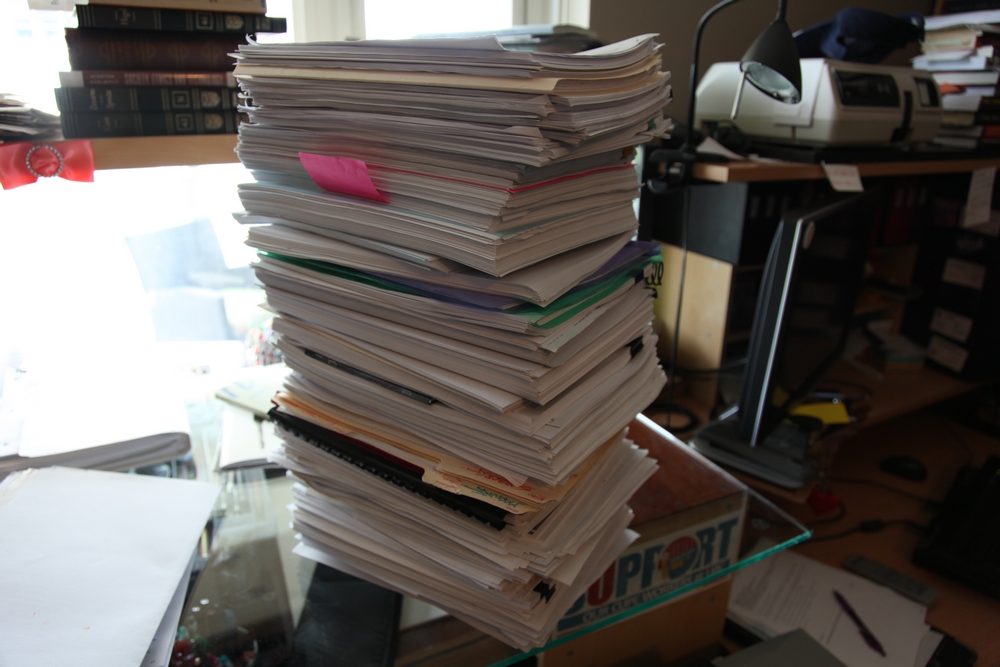

May, 2014: this is the past thirteen months or so of graduate student theses and dissertations, directed studies, and other brilliant scholarship. I read every page. My head hurts -- in a good way.

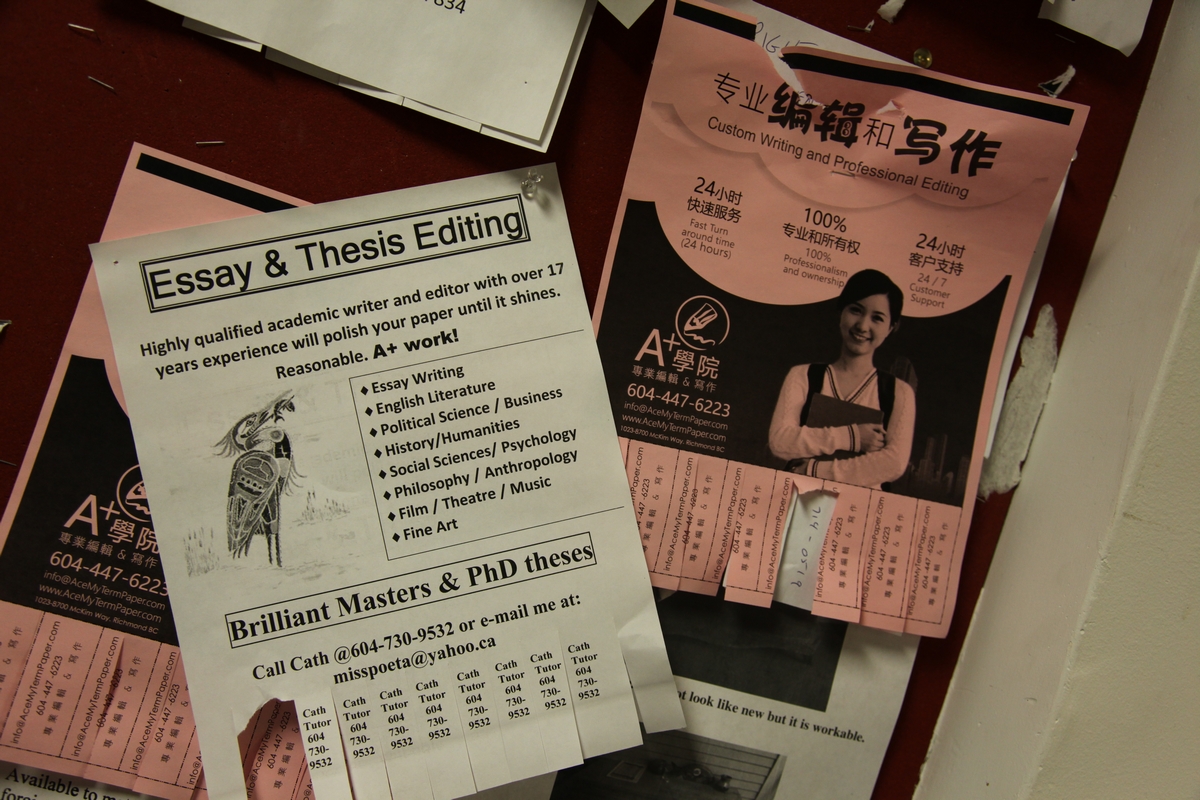

The Cheating Market at UBC

(Bulletin board in the Student Union Building, November 2014)

Wow! Thank you!

If there's anything interesting or useful here, I promise that it's inspired by previous generations of students, and how they have taught me how to struggle to make sense of a fascinating, turbulent urban world...

Left anonymously at the end of a Cities lecture in the large Geography Room 100 lecture hall, November 2015

I love teaching, but I hate assigning grades -- sifting and sorting in order to come up with a single, one-dimensional hierarchy from "excellent" to "good" to "fair" to "poor." My pedagogy is shaped by the obscure but fascinating history of the statistical technique known as multidimensional scaling. Sadly, in a world of evolutionary and increasingly automated hierarchies -- from your GPA to your learning-management-system "engagement index" to your credit score to your income or net worth -- I am not allowed to provide marks on a multidimensional scale. I am forced to put everyone through the meat-grinder in order to come up with a single, one-dimensional ranking.

*Blush*...

This is quite flattering, and makes me think deeply about the challenges many students are facing at this competitive place of mind...

"Dear Dr. Wyly,

The Faculties of Arts and Science are collaborating with the Office of the Vice President, Students and the Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy on a Teaching and Learning Enhancement Fund project to identify teaching practices that support student mental health and wellbeing and explore the connections between learning, academic success and student wellbeing.

In a previous phase of the study, students nominated you as an instructor whose teaching practices support mental health and wellbeing. We would like to invite you to an interview to learn more about your teaching practices – for example, what inspired you to adopt your current approach to teaching, how has it evolved over the years, and how do you implement it? Participation in this project requires a single 30-60 minute interview, to be scheduled at a convenient time and location.

Further details about the study can be found in the attached Consent Form. We will be conducting the interviews throughout the month of February. If you are interested in participating, please let me know by responding to this email with your availability."

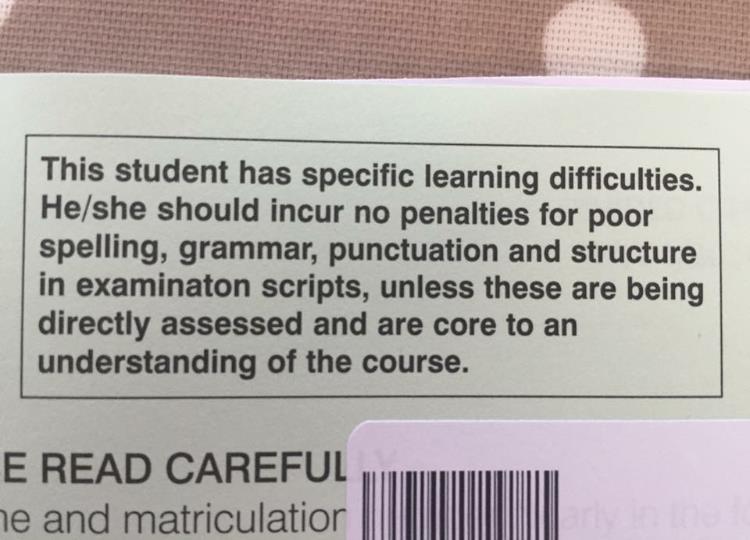

Unintentional Irony

Bureaucratic edicts on what can, and what cannot, be evaluated. Courtesy of Tom Slater, April 2016.

If you plagiarize, you will become famous

in all the wrong ways

"Mr. Trump was especially eager to steer their convention back on course with fiery speeches and warnings about electing Hillary Clinton after days of confusion and recriminations over Melania Trump’s tarnished speech. The turmoil over Ms. Trump’s speech, which borrowed lines from Michelle Obama’s 2008 convention address, eclipsed the party gathering in a way not seen at a political convention since Dick Morris, Bill Clinton’s adviser, was revealed at the outset of Mr. Clinton’s 1996 convention to having had an extramarital affair and a foot fetish."

Patrick Healy and Jonathan Martin (2016). "Ted Cruz Stirs Convention Fury in Pointed Snub of Donald Trump." New York Times, July 20.

*

Contra Educacion Capitalista!

Santiago, Chile

Protect Yourself

"Calling Bullshit has been developed by Carl Bergstrom and Jevin West to meet what we see as a major need in higher education nationwide." See, especially, their How Do You Know a Paper is Legit?

In the long rainy Vancouver winters, when every office of the UBC bureaucracy is running its spambot rules-and-regulations email directives at warp speed, I get really, really depressed. Not long ago, I was threatened with litigation when an applicant failed to gain admission to our doctoral program. Did I really sign up for this? Then, every once in a while, I get a very different kind of email, and this keeps me going. Yes, I did sign up for this.

"I just wanted to personally thank you for all the time and effort that you put in to helping me get by a significant milestone on Friday. You were literally the only person saying 'you can do it' at several points when I was about to quit."

--from an anonymous Doctoral Candidate who successfully defended a Ph.D. after a long road of analytical challenges, amidst truly oppressive time-space constraints of balancing full-time employment in an oppressive cognitive-capitalist enterprise.

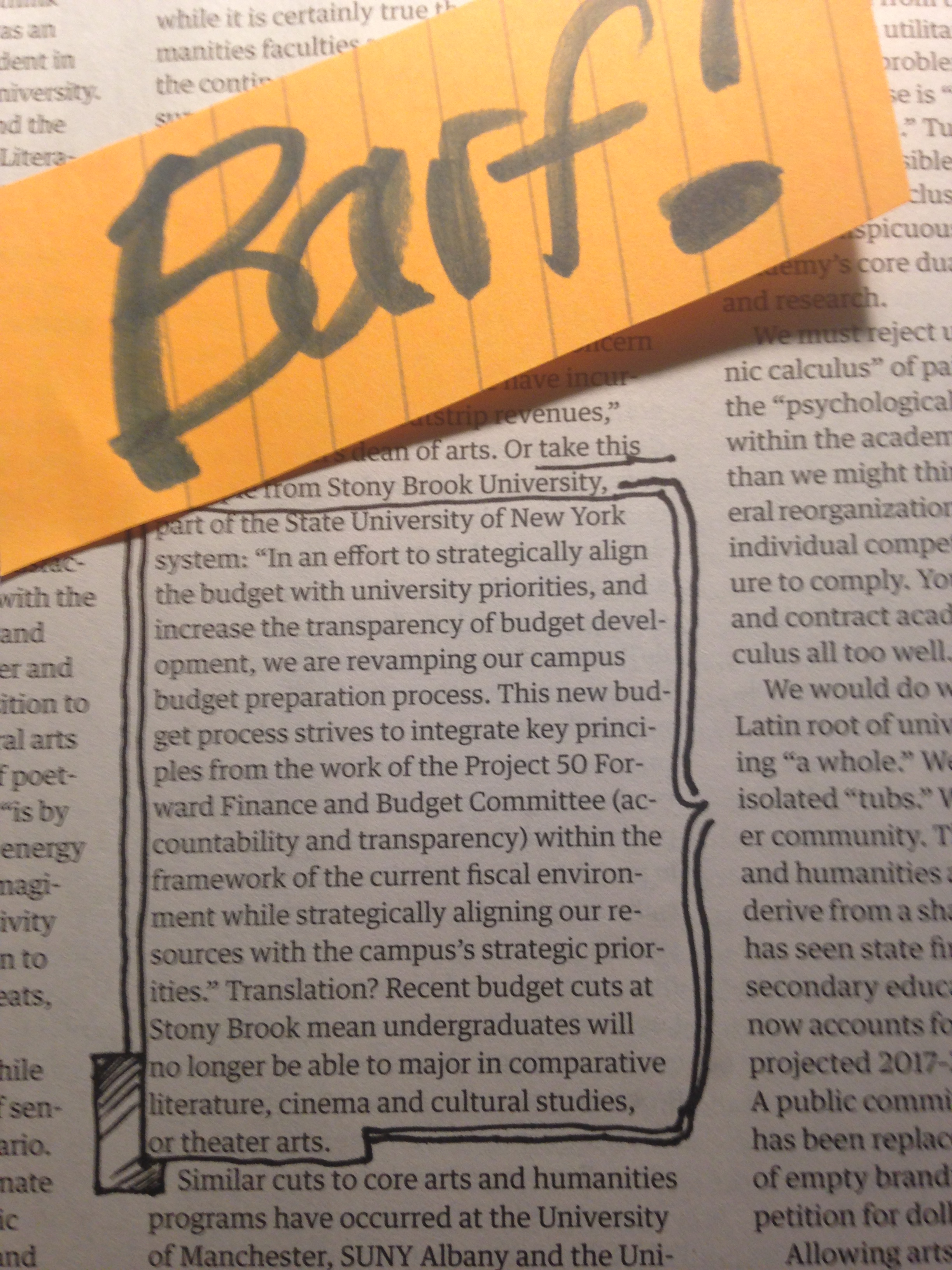

From James Compton (2017). "Ode on an Academic Urn." CAUT Bulletin, June, p. 7.

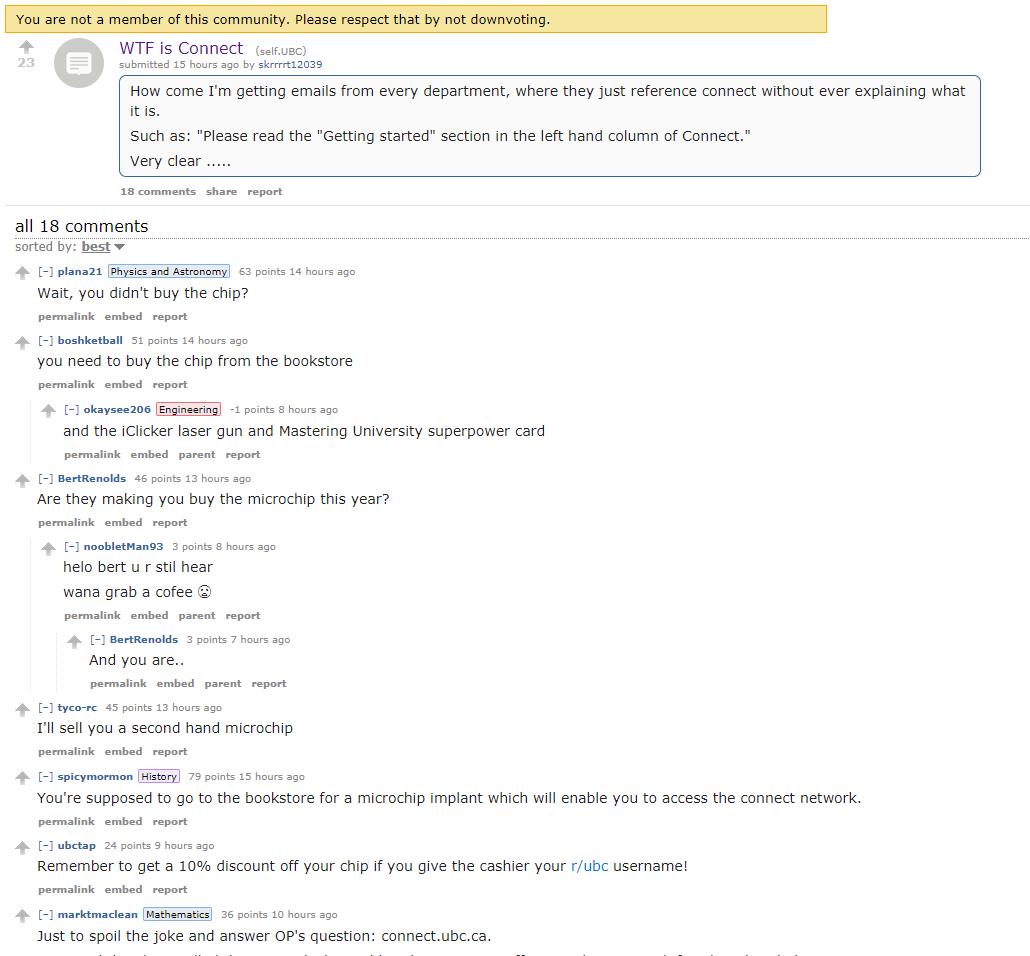

WTF Connect?

From a discussion thread on reddit/r/ubc, September, 2017. Note how a confused new student's question quickly descends into a hilarious trolling party, with detailed advice on where to buy the "chip implant" to embed into your brain so that you can access an educational experience at UBC. A Place of Mind!

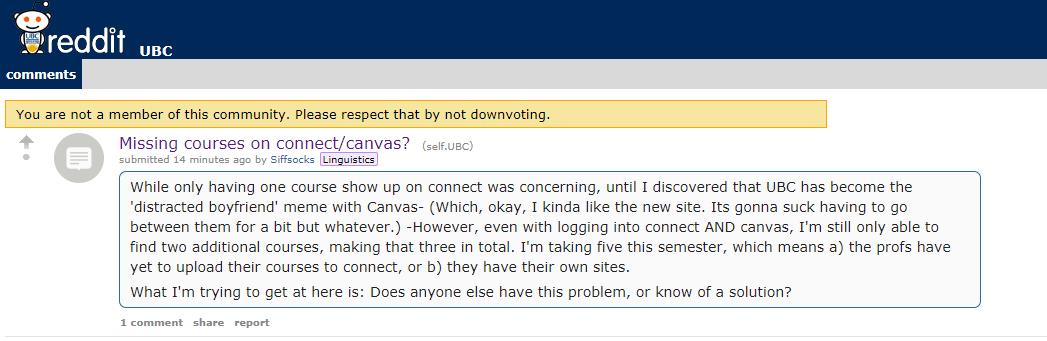

More cybernetic teaching confusions .... reddit/r/ubc, September 2017

Thinking about grading, while SkyTraining. Part of my philosophy, my own personal Cartesian-cognitive-curriculum on the matter of assigning grades, is shaped by a multivariate yet non-hierarchical methodology known as multidimensional scaling. See this.

Courtesy of Tom Slater, October 2017

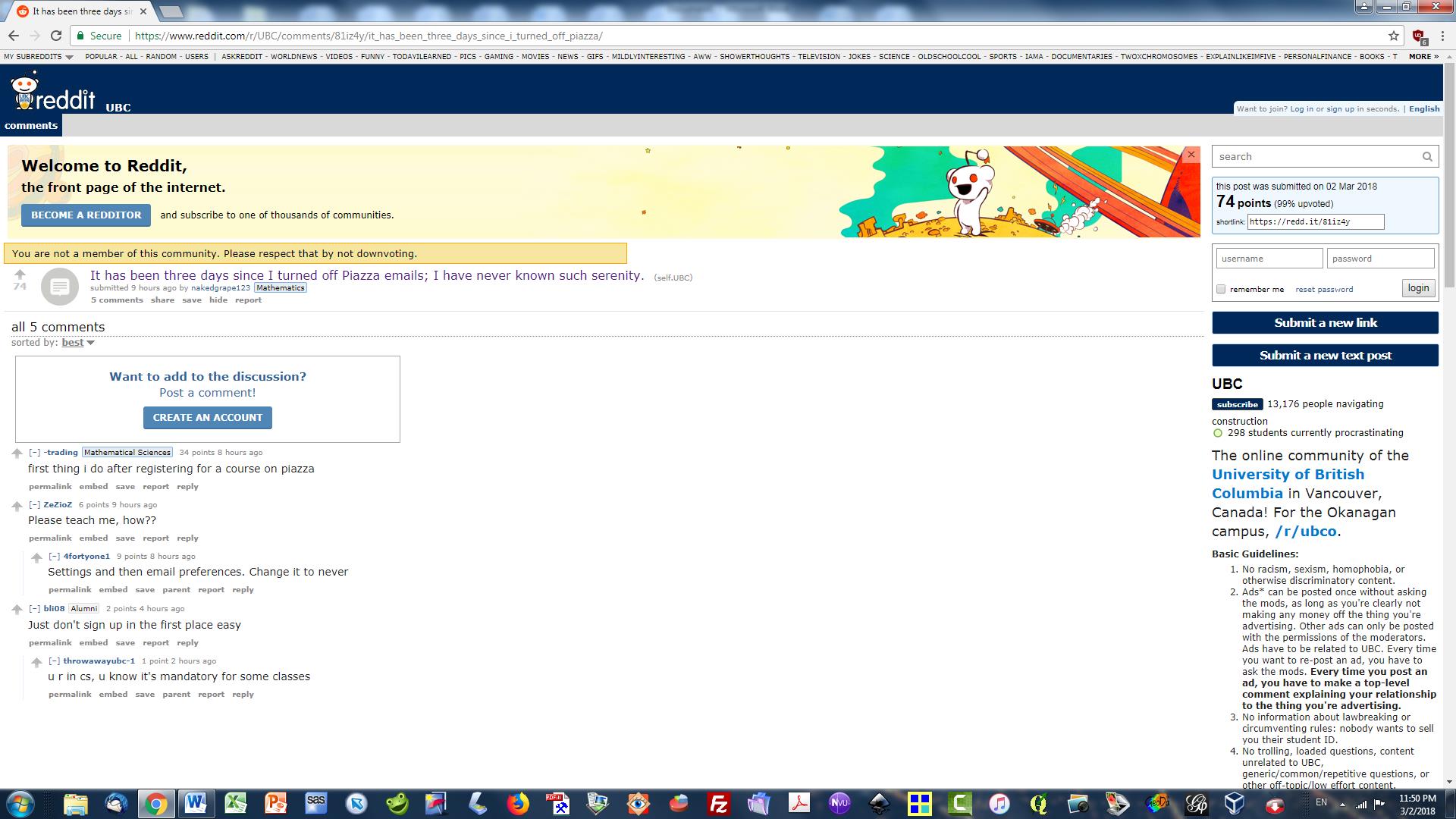

"It has been three days since I turned off Piazza emails; I have never known such serenity."

Cognitive Capitalist Sifting and Sorting

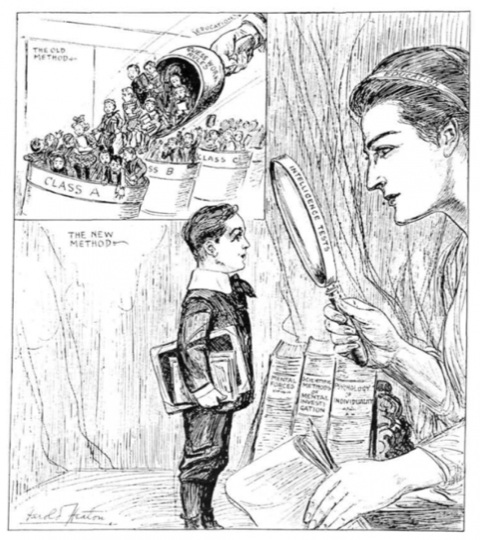

The image is from the cover of a publication called The School Board Journal, in 1922. It was distributed by a critical education technology blogger (Audrey Watters Hack Education Weekly Newsletter), and in turn shared by Dr. Luke Bergmann. The image, as well as some of Bergmann's insights and Watters' critiques of contemporary educational technologies, make me think of some of the issues we explored in Planetary Kantsaywhere.

"A lot of [UBC Board of Governors] discussion circles around ideas of reputation and brand. Who pays and how much they pay (be they governments, donors, or students) is also a big deal. Cultivating a good experience for students is central to many of these discussions.

What is this experience that everyone is talking about? I hear about classroom experience, residence experience, and student experience writ large. Very little of it seems to be specifically tied to learning (unless it’s about more engaging, entertaining, learning with technology). While I’m sure some Board colleagues will disagree with this conclusion, it does seem to me that the experience being touted is really the experience of a customer seeking fulfilment through the purchase of a service. What is seen as important is not what is learned, but the grade; not the productive struggle of learning but the validation of self in a great experience as a member of an imagined community. A good student experience very likely leads to a productive alumni relationship — one where the alumni feels good about giving money.

If you are seeking an experience, take a year off and hike the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail. Go to a circus. If you want an education then head on over to a lecture, read a book, join a seminar. Let’s focus on the real learning that is made possible by your faculty..."

Charles Menzies (2018). "'Student Experience' Should Not Come at the Expense of Faculty." Ubyssey, April 18.

Yikes! Posted to a Reddit Discussion Forum, July 2018. Perhaps the driver is listening to Leenda Dong.

Included here pursuant to the Mashup provision of the Canada Copyright Act

WTF?

Behold the History Before it Disappears

"AMS Council has unanimously voted to ban using posters to campaign in the society’s elections. This amendment, voted on at the April 3 Council meeting, comes after the use of posters was criticized for generating waste, consuming significant financial resources and requiring time-consuming efforts to ensure campaign regulations are followed. Outgoing AMS Elections Administrator Halla Bertrand believed that it was important to “prohibit postering explicitly.” Maneevak Bajaj (2019). "AMS Council Votes to Ban Postering in Future Elections." The Ubyssey, April 13.

"The race you’re running has only one competitor, and it’s you."

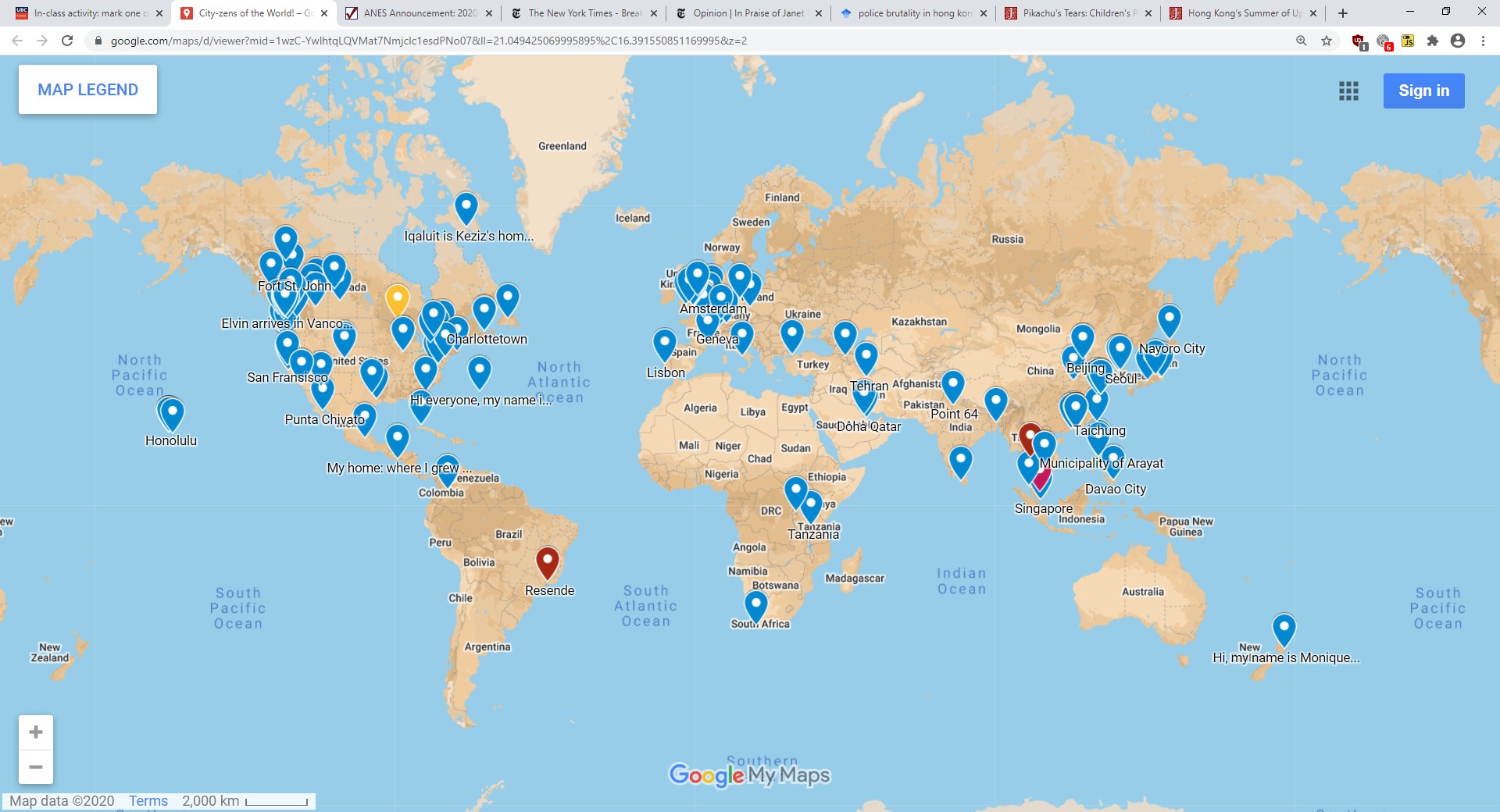

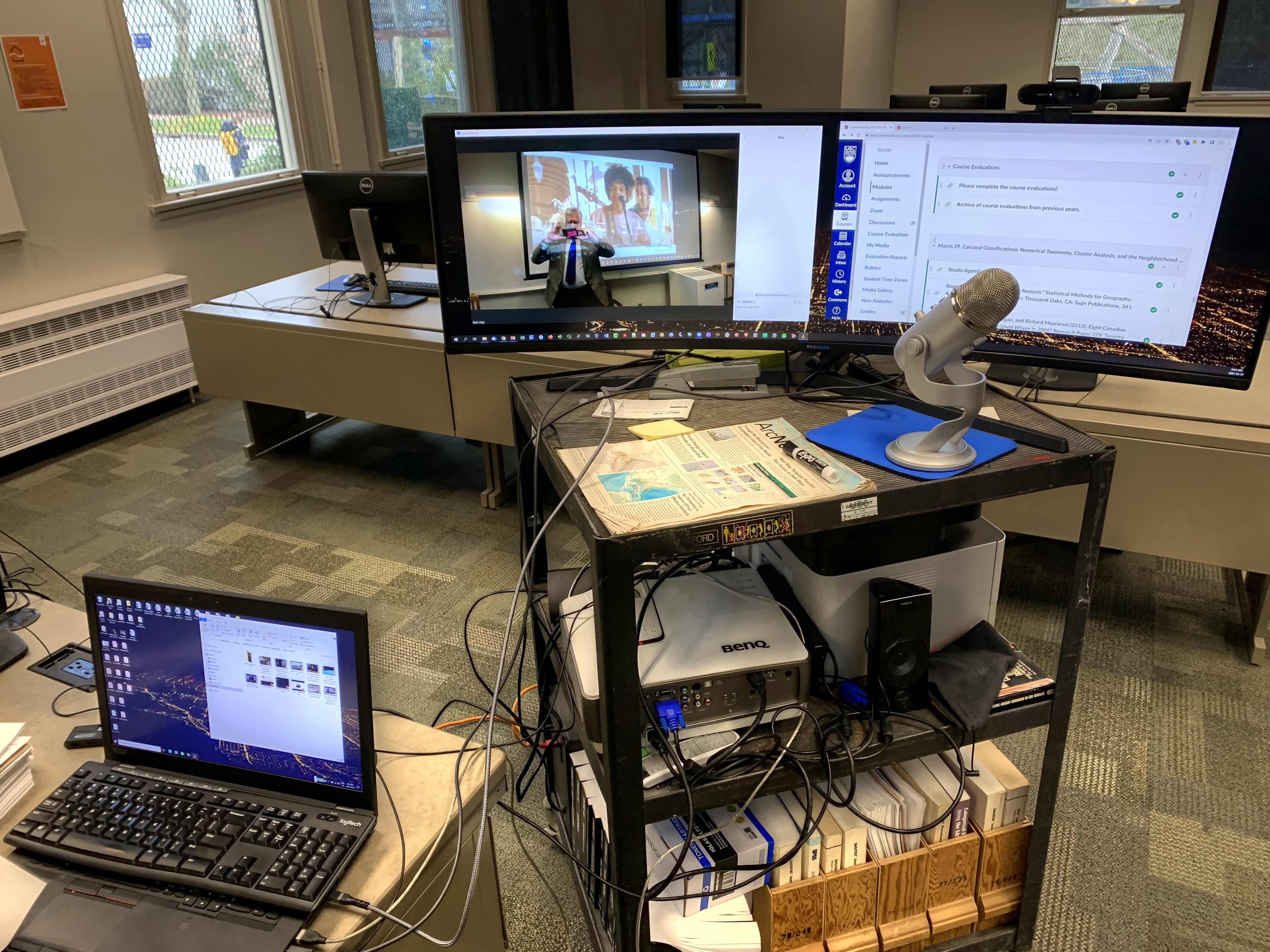

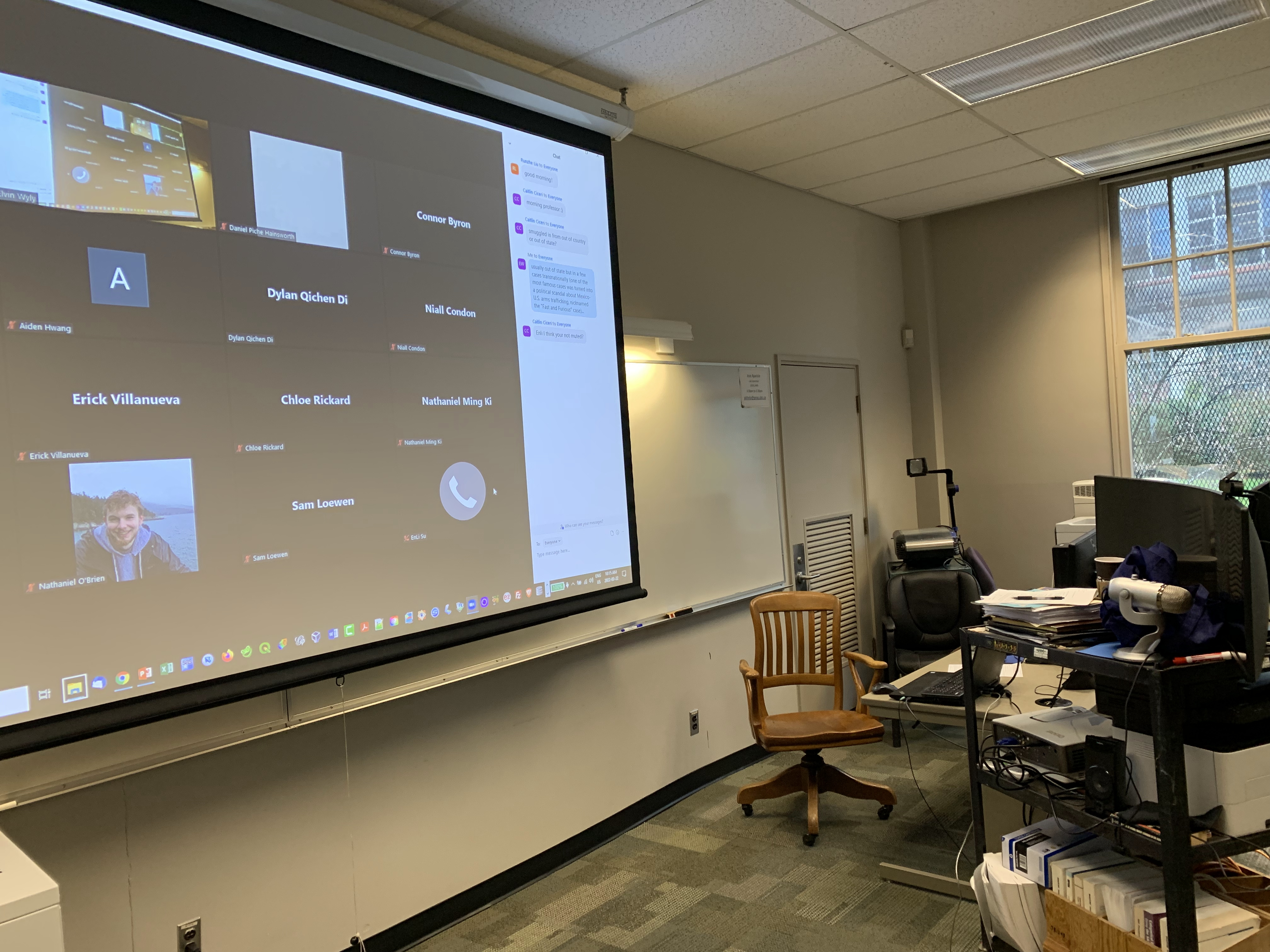

Cityzens of the World (cf. Appiah, 1997), Fall 2020

Students in Urst 200 / Geog 250, Fall 2020

Teaching

...has changed so much in the last few years, hasn't it?

Notes below are all pre-pandemic, dating from late 2019 back in time to somewhere circa 2002. So be warned, the digital fragments chart a curious sort of cybernetic, evolutionary obsolescence!