General Guidelines for Written Projects

This page offers guidelines, suggestions, and advice for preparing written projects for my courses. I encourage creativity and innovation as you seek to find your voice as a scholar, writer, and urbanist. But there are limits, and so I've prepared these notes to help answer common questions. I apologize for the length and detail of all the stuff on this page: the vast majority of these guidelines are nothing more than common sense.

Unfortunately, I've discovered over the years that common sense is not so common anymore. Students at UBC are brilliant and talented in many ways, but there is very little common ground and shared understanding of how scholarship should be done. People are brilliant in every possible direction, often in unpredictable and contradictory ways. So it's necessary to provide very clear, detailed answers to the many questions people ask.

You should use your good judgment. In some cases this might mean disregarding my advice on a particular topic, because you've thought about it seriously, and you've decided that you've found a better way. For certain aspects of the writing process, that's fine. For other aspects -- like the rules on citation and avoiding plagiarism -- you should follow instructions much more closely.

Let me know if you have any questions, comments, or suggestions about any of these guidelines. For more details, see the explanations on the guidelines in the right column below. (In the left column are various quotes and reflections on writing, academic integrity, and related issues.)

Seven Simple Guidelines

1. Introduce yourself.

2. Use simple, clear formatting.

3. Be original. Avoid cut and paste.

4. Be careful in the WikiWorld.

5. Choose a citation style, and use it generously and consistently.

6. Write for an audience of humans, not computers.

7. Include references to scholarly sources.

1. Introduce yourself. Clearly identify yourself as the author. Take credit for your hard work by declaring your honesty and integrity. All paper submissions must include a signed declaration on the first page. Here is a sample of the kind of declaration I'm looking for:

"I, [your name], promise that this is my own work. No part of this work has been plagiarized. I have written this myself, without any help from a tutor, hired impersonator or ghostwriter, or artificial intelligence algorithm. This work has not been submitted for academic credit for any other course. I understand that there are severe penalties for academic misconduct, and that in the age of the internet there is no statute of limitations on this transgression." Then sign your name.

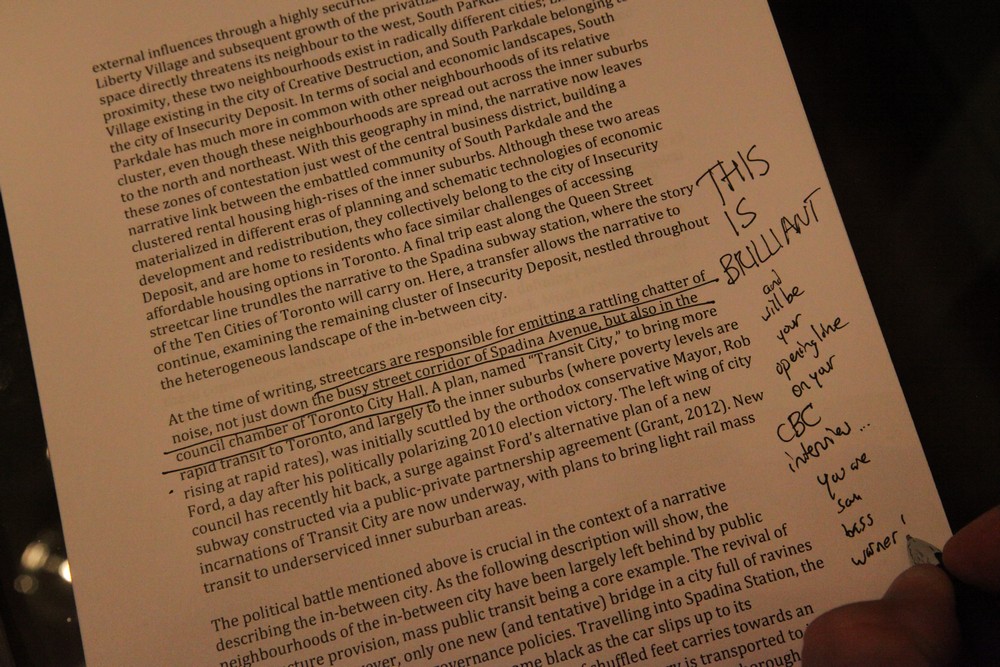

Use your own words, and write out your declaration by hand. Be creative; here's one recent sample of a student's creative declaration. Do not just cut and paste the declaration I've written above. If you do, it will be a red flag that you regularly use cut and paste -- and of course that's the speedy route to plagiarism.

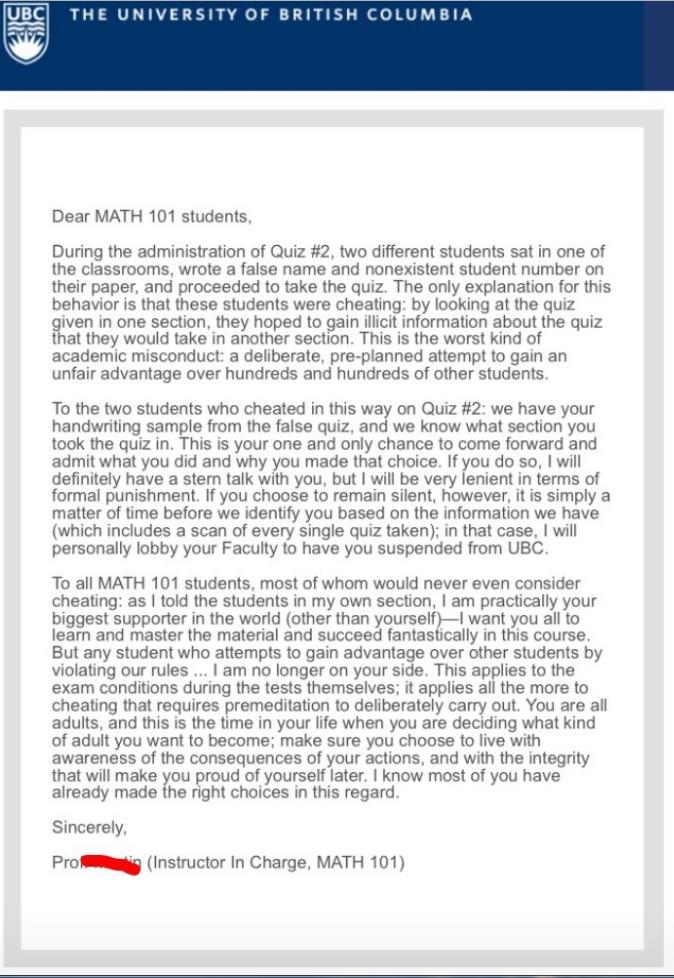

Please note that I reserve the right to conduct an oral examination on the content of your paper. These certifications are now required because of rampant plagiarism that has spawned a vast surveillance industry built upon the doctrine of guilty-until-proven innocent (i.e., Turnitin.com). I would like to trust you completely, Renee Zellweger-you-had-me-at-hello style -- but in order to do that, I need you to ask for my trust explicitly. That's why this declaration is now required. If you do not include this kind of certification, it will be a clear indication that you have not read even the first of these guidelines -- and thus there is no guarantee that you've understood UBC's policies on academic integrity and plagiarism (and my interpretations of these regulations). Therefore, any paper submissions that fail to include the certification will receive a mark of 0 until such time as a declaration is received.

Frequently Asked Question: "What are UBC's policies on academic integrity?"

Answer 1: The official UBC rules are described here.

Answer 2: For my interpretations of these regulations ... read the rest of this page.

In general it's a good idea to include your name and preferred contact information in the top right-hand corner of each page of your submission, even though the Canvas online submission system does keep track of some of this information.

Keep an archived copy of your submission on file. It's been many years -- literally decades! -- since I've experienced any documented instance of a lost paper submission, but technical and logistical complications do happen from time to time.

2. Use simple, clear formatting. In word-processing, the KISS principle applies (In business, this acronym means "keep it simple, stupid!", but my friend Paul Plummer reminds me that the original meaning came from a physicist, who advised people to "keep it sophisticatedly simple.") I recommend that you use a standard font like Times New Roman, 12 point, left-justified, double-spaced, and typed on one side only of standard, 8.5 x 11.0 inch white paper. Use bold, italics, and underline codes where appropriate to draw emphasis to certain key points; but avoid the temptation to try to use all the fancy fonts and technical wizardry of the software. (I could have written these guidelines in a 72-point dingbat font that flashes and bounces back and forth, but just because something is possible in a pull-down menu in a software package doesn't mean that it's a good idea.) Fancy technical adornments do not compensate for poor thinking or writing.

On the other hand, you can disregard these guidelines if you really do have accomplished graphic design skills that help you tell a convincing urban story through the judicious use of customized typefaces, layouts, graphs, charts, and other kinds of illustrations.

3. Be original. Avoid cut and paste. Cutting and pasting a chart, graph, map, or photograph from the internet is not an original contribution. If your original argument, interpretation, or analysis can be illustrated with a graphic or photograph that you've found somewhere, then yes, by all means you're encouraged to use that work under the provisions of fair use and fair dealing. But be very careful to acknowledge your sources completely. Anything less is dishonest. A caption should appear below any material you've taken from another source:

Your Title for the Image or Illustration. Source: Author, institution, or other entity that created the work (year). Description (e.g., Advertisement, photograph published in newspaper or magazine, chart published in journal article), and further publication information (e.g., name and date of newspaper, magazine, journal, or concise internet address). © [Name of copyright holder], reproduced here under fair use / fair dealing provisions.

There is some disagreement on how tables, maps, photographs, and other items should be referenced in the body of a paper. Many publishers require a clear distinction, with references to "Table 1" versus "Figure 1." My own thinking on this has evolved. I'm less concerned with the exact way you refer to various graphical elements, and more concerned that you properly acknowledge the source of things you've borrowed, and that you do so consistently. So it's fine to use creative titles as captions for tables, figures, charts, and all other kinds of graphical items -- so long as you properly reference the original sources.

Never, ever cut and paste text. Type out the words yourself, using care to provide "quotes in the right place to indicate the words of the author." Even better, write out the notes, quotes, and outlines for your paper by hand, and then revise and refine things when you're ready to type up a first draft.

If you want other advice on writing, you may be interested in this.

Cutting and pasting text dramatically increases the chances of unintentional plagiarism. Unintentional plagiarism is still plagiarism. When plagiarism happens, it doesn't help to claim that it was an accident. In recent years, quite a few best-selling authors have been at the center of major scandals when it became clear that passages in their books were lifted directly from other publications without appropriate citation. Several celebrity authors tried to defend themselves by saying that it was all an accident, that they had just inserted the material given to them by their assistants without checking the details themselves. A similar scandal played out in September, 2008, when Canadian Liberal Party researchers found numerous lines in a March 2003 speech delivered in Parliament by then Opposition Leader Stephen Harper that had been lifted directly without attribution from a speech given two days earlier by Australian Prime Minister John Howard. Owen Lippert, who had been working in the Opposition Leader's office in 2003, stepped forward to say that he had written the speech, and that he had been "overzealous" in copying passages from Howard's speech. In an intersection of multiple ironies, Lippert, who holds a Ph.D. in modern European history, once worked as a Senior Policy Analyst at the Fraser Institute, and he once taught at UBC. Even more ironic, he is described as an expert on intellectual property. (See Canadian Press (2008). "Grits Continue Their Attack Over Iraq Speech." The Globe and Mail, October 1).

Scandals like these erupt all the time, it seems. But when celebrity authors blame their assistants, or when political leaders' assistants step forward to say that they did the writing and the (unintentional) plagiarism, that just makes the situation worse. The author winds up admitting that they did not actually write the book that has their name on it; the political leader admits the (widely known but also widely lamented) fact that their speeches are written by other people. Sadly, academic corruption has gone mainstream: in China, the "science cop" Fang Shimin runs the New Threads web site, a Watergate-style "deep throat" source that documents credible allegations of academic dishonesty. Among the Top 10 stories of 2009: a dozen university presidents and vice-presidents accused of plagiarism; a university president who falsely claimed winning a prestigious scientific prize; two professors who faked research results published in an international journal; and a medical doctor who inflated the success rate for a new surgical procedure. See Paul Mooney (2010). "Lie Detector." South China Morning Post, PostMagazine, January 31, 16-19. These kinds of dishonesties over ideas, research, and creativity have, quite literally, spread like an infection through areas of inquiry that have life and death consequences. Pharmaceutical companies have become aggressive in ghostwriting studies purportedly conducted by independent medical researchers; the problem has become so bad that one medical journal has now announced a policy of "ghostbusting" to investigate cases where articles may have been written by paid, company employees with direct conflicts of interest. See Natasha Singer and Duff Wilson (2009). "Unmasking the Ghosts." New York Times, September 17. This stuff gets serious. Not long ago, the Federal Court of Canada stepped in to overturn the decision of an un-named member of the Immigration Review Board (IRB), whose decision was "corrupted by errors" in ways that suggested that the member was "merely cutting and pasting from other rejected claims" when rejecting the claim of a Mexican claimant. Janet Dench, Executive Director of the Canadian Council for Refugees, reminded a reporter of the stakes of this particular kind of plagiarism: "Unfortunately, the consequences of bad decisions can be death. We have seen cases of people being sent back to Mexico from Canada who have been killed and attacked." See Adrian Humphreys (2011). "IRB Judge's Ruling A Jumble of 'Errors.'" National Post, October 22, A4.

I'm always struck by a combination of horror and amusement when I read these scandals. I write my own stuff (slowly, with lots of flaws and all sorts of other problems). I don't steal the work of assistants. If someone is helping me with a project and I wind up using anything significant at all from that help, then we are listed properly as coauthors. See, for example:

Wyly, Elvin K., Mona Atia, Holly Foxcroft, Daniel J. Hammel, and Kelly Phillips-Watts (2006). "American Home: Predatory Mortgage Capital and Neighbourhood Spaces of Race and Class Exploitation in the United States." Geografiska Annaler B, Human Geography 88(1), 105-132.

If you want to explore other implications of the "cut and paste" culture of new technology and the social-network transformations of Web 2.0, there are a lot of books out there. Even as they document the evolving cultures of boundary transgressions, some of these books themselves push the limits of acceptable practice, walking the line between the insurgent, democratizing culture of the mashup and the fraudulent deceptions of plagiarism. I strongly support the sentiment of declarations like this: "Who owns the music and the rest of our culture? We do -- all of us -- though not all of us know it yet. Reality cannot be copyrighted." But I am also committed to the achievements of scholarly integrity and authorial accountability that maintain simple, reasonable requirements -- such as the requirement that I make it perfectly clear that this quote is not my own creation. In fact, it's a quote from a book by David Shields, Reality Hunger. I read about Shields' book in a review essay published by the New York Times. Here's the really troubling part: David Shields didn't come up with that quotation on his own. The quote "is itself an unacknowledged reworking of remarks by the cyberpunk author William Gibson." See:

Kakutani, Michiko (2010). "Texts Without Context." New York Times, Arts & Leisure section, March 21.

To be sure, there are some tough cases and some gray areas. The ethical ban on plagiarism should not terrorize you. In fact, we students and scholars working in colleges and universities have it pretty easy -- it's a simple matter of 1) including a citation anytime you borrow something from another author, 2) including quote marks to indicate clearly where your work ends and another's begins, anytime you use specific words or sentences from someone else, and 3) providing clear author and source information anytime you borrow or reproduce some else's data, photographs, maps or other works. That's all it takes -- cite your sources. You're free to use the work of other people -- so long as you do not deceive the reader into believing that you created something you didn't. Citation is a powerful thing. "Cite" comes from the Latin citare, which is derived from citus, which means "quick"; citus is also the past participle of cire, "to put in motion, to excite." I had to look up the etymology, and thus it's appropriate to put things in motion with a citation (G&C Merriam, 1943. Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Fifth Edition. Springfield, MA: G&C Merriam Co., quotations from p. 184.)

So scholars like us have it easy -- we can use lots of resources out there so long as we cite our sources in order to clarify what we've done, and what we've borrowed. Doing that can be much harder in other modes of creative production -- composing music, writing novels, plays, or screenplays. If you want to learn more about some of the blurry dualisms between individual and collective, collaboration and co-optation, imitation and theft, then take a look at this:

4. Be careful in the WikiWorld. Many students use Google, Wikipedia, and similar sources for a convenient first step. This is fine. (It has taken more than a decade of hard work, but my best students have taught me that they have earned that trust; so that three-word sentence was actually written collectively by the hundreds of hardworking and talented students who took classes with me over the years. I have to acknowledge this to avoid any possibility of plagiarism!)

The WikiWorld is fine for the first phases of research, when you are trying to get your bearings on a particular subject. It's also great for checking out what people are saying about a particular topic. And, of course,

- Wikipedia is a convenient and powerful way to look up the basic facts of uncontroversial events or topics.*

So, now you're asking, "if it's so convenient and powerful, why is elvin saying we need to be careful?" Great question. The problem is that annoying asterisk above. You know how marketing and advertising work. There's always an asterisk, and when you see it you know to look for the fine print.

So here is the fine print:

- The question of what counts as a "fact" no longer has universal agreement. Many subjects once regarded as fact are now subject to intense, polarizing debate in politics and cultural life. Some say evolution is science, but a few say it's just a theory. Most say climate change is real and caused by human activity, but a few say it's not. Some say feng shui is essential for a good life, and others say it's just another penny-stock promotion in an intoxicated real-estate market. And so on... Even if (especially if) you think any of these disputes are a bit misguided, you still need to be aware of their existence. Aha! That gives them a certain performative reality!

So, what this means is that having a powerful way to look up the basic facts of uncontroversial events or topics is nice as a first step. But then it very quickly gets very risky. That's because the information is often provided anonymously by individuals whose knowledge and motivations are not always clear. "Expertise" in the algorithmic digital world becomes a strange thing, based on the collective. That has some wonderful, utopian possibilites. But good utopians realize that any and all possible worlds will have more than a few nutcases!

Be very careful. If you are inclined to trust Google or any other search engine as your preferred and most reliable way of beginning research, then you must first read this important short essay summarizing a scientific study of information practices:

Wineburg, Sam, and Sarah McGrew (2016). "Why Students Can't Google Their Way to the Truth - Fact-checkers and students approach websites differently." Education Week, November 1.

Wikipedia has been dissed by some of its own early pioneers and creative inspirations. The open-source creator Eric Raymond argues that Wikipedia is "infested with moonbats," and one of the site's early developers, Larry Sanger, described the recent evolution of content standards on the site this way: "Wikipedia has gone from a nearly perfect anarchy to an anarchy with gang rule." (quoted in Schiff, 2006, p. 42). Politically contentious topics generate violent virtual wars of edits and counter-edits, and in an online community with unlimited combinations of interests and pet peeves, almost anything can become politically contentious. There have been multiple cases of fabrication, libel, and self-serving edits by politicians seeking to polish entries on themselves. The site's edit wars also reflect the rise of conservative ideologues' war on science and modernist knowledge -- creationists and Intelligent Design advocates fighting against the teaching of evolution, the "birthers" who question Barack Obama's birth certificate as a way of undermining Presidential legitimacy, Holocaust deniers, climate-change deniers, and revisionist historians working to erase the significance of slavery as a factor in the U.S. Civil War (see Levin, 2011).

The online world is great for free speech and free expression, just like street corners and dive bars and talk radio. But free speech is not necessarily intelligent or well-informed speech.

Even so, we cannot deny that Wikipedia has become deeply influential in today's online culture. It is becoming a latter-day version of the landmark reference work launched in 1768 (the Encyclopedia Britannica). Not long ago, the site became the seventeenth most popular site on the internet -- site traffic has been doubling every four months, sometimes hitting fourteen thousand viewers per second (Schiff, 2006). I also cannot deny that Wikipedia is gaining some credibility among some faculty in colleges and universities (Press, 2011).

Therefore, this particular recommendation is not an absolute prohibition. It's got lots of loopholes and exceptions. The recommendations on this page are guidelines, and I take seriously the very subtle distinctions between the alternative definitions of the word that comes from the French guider. One of those definitions specifies "to control, direct, influence," but other meanings are a bit less coercive: "to direct the course of, steer," or even better "to go before or with in order to show the way." (Cayne, 1990, p. 427). Part of what you're learning in university life is that knowledge is contested, and so are the rules; so what matters most is critical thinking and good judgement. But of course good judgement requires a lot more time and consideration. That's why the short headline above cuts to the chase for people searching for quick answers, and tells you to avoid Wikipedia and related anarchies. But if you've read beyond the headline and you're wading through this long discussion, then I'm happy to admit that this is a gray area. What matters is that you use good judgement. I recommend that you avoid using Wikipedia in an uncritical, un-reflective way -- especially if you're researching a topic where there are likely to be Wiki-edit-wars. I recommend that you read enough about Wikipedia so that you have a critical perspective on its strengths and flaws (see Liu, 2008; Schiff, 2006; Press, 2011). I'm inspired by the metaphor offered by Lisa Dempster, a teacher-librarian at Riverdale Collegiate in Toronto (see Press, 2011); she likens the use of Wikipedia to talking to your neighbor. It's a good place to hear about what's happening, and it's a good place to start when you're trying to learn about something. But it's not the only source you should use.

So if you use Wikipedia, make sure it's not your primary source, and not your only source. When a paper includes repeated citations to Wikipedia, it is a clear signal that the writer does not know of, or is not willing to search for, books or articles that have gone through the process of peer review before being published. As Wikipedia becomes more popular, its social meaning changes. Specifically: the quickest way to tell a reader that you're lazy is to cite Wikipedia as a primary source, and your main source. The fact that Wikipedia appears at the top of the list in Google searches means that it has become the instantly-recognized icon of intellectual laziness.

References

Cayne, Bernard, ed. (1990). Webster's New World Encyclopedic Dictionary. New York: Lexicon Publications.

Levin, Kevin M. (2011). "Teaching Civil War History 2.0." New York Times, Opinionator section, January 21.

Liu, Alan (2008). To the Student: Appropriate Use of Wikipedia. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California, Santa Barbara, Department of English.

Press, Jordan (2011). "Wikipedia Gaining Respect in Places of Higher Learning." The Vancouver Sun, November 5, B5.

Schiff, Stacy (2006). "Know it All: Can Wikipedia Conquer Expertise?" The New Yorker, July 31, 36-43.

Wineburg, Sam, and Sarah McGrew (2016). "Why Students Can't Google Their Way to the Truth - Fact-checkers and students approach websites differently." Education Week, November 1.

5. Choose a citation style, and use it generously and consistently. Document all sources for material that is not your own. Anything that is not your own should be referenced with full source information. Footnotes and other reference materials are not counted towards the word limits for project submissions; when in doubt, provide a citation.

You can use any recognized citation style, but be consistent. Personally, as a reader, I like the style that presents footnotes at the bottom of the page, or perhaps endnotes with details that appear at the end of the document. But more and more, the standard approach is now the Harvard, in-text reference style, which presents in-text citations (such as Galbraith, 1954; Gray and Wyly, 2007; Wyly et al., 2008), with page numbers for specific quotes, such as Gray and Wyly's (2008, p. 331) portrayal of security and militarization policies in post-9/11 U.S. cities as part of a "a genuinely new narrative object." And then at the end of the paper you see this:

References

Galbraith, John Kenneth (1954). The Great Crash 1929. New York: Time, Inc.

Gray, Mitchell, and Elvin K. Wyly (2007). "The Terror City Hypothesis." In Derek Gregory and Allan Pred, editors, Violent Geographies: Fear, Terror, and Political Violence, pp. 329-348. London and New York: Routledge.

Wyly, Elvin K., Markus Moos, Holly Foxcroft, and Emmanuel Kabahizi (2008). "Subprime Mortgage Segmentation in the American Urban System." Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 99(1), 3-23.

You'll find a mixture of different citation styles in the readings, lecture notes, and other materials in my courses -- some footnotes, some in-text Harvard style, and so on. The most important thing is to choose a style and use it generously and consistently, and to avoid cutting-and-pasting universal resource locator (URL) hyperlinks. That brings us to the next guideline.

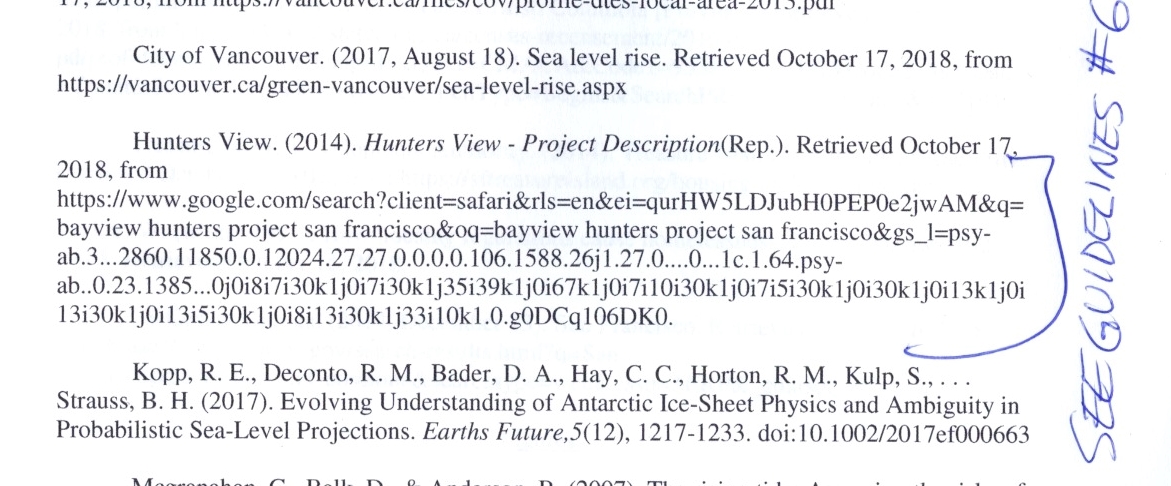

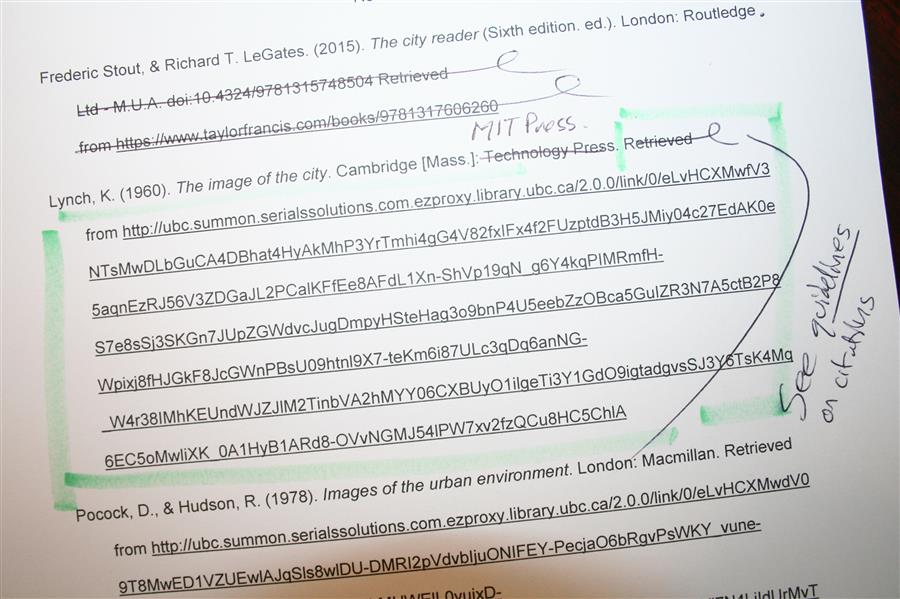

6. Write for an audience of humans, not computers. The automation of many parts of what has been understood for centuries as "writing" has seriously threatened communications skills (see, for example, Baron, 2015). This danger is most apparent in the proliferation of long computer-generated codes in footnotes, endnotes, and bibliographies. I ask that you write for an audience of people, not computers. Complete citation involves recognizing the author, year, title of work, and location or institution publishing the material. The purpose of citation is to a) give credit for ideas and evidence that are not your own, b) demonstrate to the reader that you've done your research with care and diligence, reading the most important sources to help you develop your knowledge and expertise on a particular topic, and c) provide useful information that will help a reader retrace some of your steps or track down interesting sources.

Use good judgment, and think carefully, when citing materials you've found on the internet. Consider two different ways of providing a reference to the same paper in a scholarly journal:

a. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.0008-3658.2005.00092.x

b. Isabel Dyck (2005). "Feminist geography, the 'everyday', and local-global relations: hidden spaces of place-making." The Canadian Geographer 49(3), 233-243.

Option a is used for computers to communicate with one another. Option b is used to communicate to human beings. Please use option b. If you use option a, it will give me a clear indication that you are using "cut and paste," and that will make me wonder if you've ignored the warnings on the danger of this practice. It does not matter whether you found Dyck's paper through Google Scholar, Blackwell-Synergy, Factiva, Academic Search Premier, Ebsco, Ingenta, or whatever other corporate information aggregator is providing you with that conveniently-ranked list of hyperlinks flooding across your screen. Don't worry about these corporate details, because by next week one of these companies will be buying another one. Several years ago, many companies began using what they call "permalinks" on their sites, because people had gotten so frustrated at the ephemeral instability of resources on the Internet. This didn't work very well with the companies buying and selling one another so fast, so then they started introducing DOIs (digital object identifiers). Next week there will be yet another acronym. Lesson: sometimes, the old fashinoned way works best. What matters is that you're using scholarship recognized to merit publication in The Canadian Geographer, a respected scholarly journal that has been around for a long time. It doesn't matter what search engine led you to The Canadian Geographer, or -- revolutionary, subversive! -- maybe you even found a physical copy on the library shelf. What matters is that you're working with good scholarship published in a good, recognized journal.

Let me emphasize this more clearly: do not include extraneous garbage in your citations. Do not include URLs (universal resource locators). Do not include DOIs (digital object identifiers). Do not include the hyperlinks or the search engines that delivered you to the source: reference the source, not the massive technological informational assemblage that is changing, at accelerating speed, producing all sorts of robotic code that is impossible for human eyes to comprehend. Yes, to be sure, you may have located your sources on the internet; but what matters is the source. If the source is only available on the internet, and has no reputation other than being an online blog or website -- then you probably shouldn't be using that source.

Write for an audience of humans, not computers. I apologize if this guideline is in direct conflict with what you are taught to do in other classes, or what you see everywhere else these days. I am very sorry. But every year I read through hundreds of student essays, and each year a smaller percentage of students seem to have taken any time to read these guidelines. So this rule -- write for an audience of humans, not computers -- has gradually evolved into a simple indicator of who is paying attention. Please, do not dump a pile of robotically-generated internet garbage on my desk. It makes the reading experience very unpleasant.

Reference

Baron, Naomi (2015). Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World. New York: Oxford University Press.

7. Include references to scholarly sources. How many? For a 200-level course, a general rule is that the ratio of unique scholarly sources to paper length should be about 1:200. If your essay is about 1,000 words, you should make references to at least five separate scholarly sources. For a 300-level course, I'd suggest a ratio of about 1:150. For a 400-level course, it could be closer to 1:100. These ratios apply to projects and final papers, of course, and not book reviews, where it is certainly more appropriate to focus mainly or exclusively on one source. These ratios are also flexible: this is a guidline, not a straightjacket. You can compensate for a very small number of scholarly citations by making each reference very significant, thoughtful, and theoretically 'deep.'

You do not have to read every single word on every single page of a book or article before you cite it; on the other hand, you should never cite something without first reading the abstract or introduction, paging through the entire piece, and reading at least a few key sections to get a feel for the essence of the work.

It's fine to cite non-scholarly materials (big-city newspapers, reputable magazines, etc.) in addition to scholarly works. But you should build on the foundation constructed by scholars just like you who studied this topic before you. Use journalism and other sources for vivid details and illustrations. But since you're a scholar, you should not ignore the hard work done by previous generations of scholars.

What is a scholarly source? This is often a judgment call, and there is some room for disagreement. But the essence of scholarship is the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake in order to contribute to human knowledge and understanding (rather than for self-serving motives of profit, celebrity, and notoriety). In general, to qualify as a scholarly source a book or article must meet three tests.

First, it must be produced by an author who is recognized as a credible expert by a non-profit, non-commercial group of other recognized experts. Yes, that last sentence had a lot of confusing terms, and it's a bit tautological. But the idea is simple: most politicians, consultants, motivational speakers, and lots of people you see on television or the internet are not scholars. These kinds of celebrities may attract big audiences, but scholarly status is not defined in terms of the size of the audience. Expertise is not a popularity contest. Most, but not all, scholars are affiliated with non-profit institutions of higher education; to obtain these affiliations, they have had to pass through multiple stages of recognition as credible experts in their field.

Second, the source must be published through a process that involves independent peer review. "Peer review" means that independent experts review a book or article manuscript when it is submitted, decide whether the work has value and integrity, and provide detailed criticisms that the author must address before the work is published. (This review and revision process takes a lot of time and effort, and that's why scholarly books and articles tend to focus on long-term changes and fundamental, lasting impacts rather than the very latest, up-to-the-minute news on a particular topic.)

Third, the source must have been produced primarily for non-profit, non-commercial purposes. If the primary goal of the author or the publisher of a work is to make money, then the scholarly status of the work is called into question. Capitalism has many virtues, but one of its vices is that it tends to distort and pervert the process of studying anything that cannot immediately turn a profit for someone. Scholarly publications produced for non-profit are much less susceptible to conflicts of interest that can undermine the integrity of the work (as one example, consider that some of the world's leading medical journals have had major scandals in recent years, after it turned out that articles on clinical trials of certain medications had been written by doctors who had accepted various forms of payment from the drug companies who stood to profit from favorable research findings on the particular drug).

All publishers have to earn a profit to stay in business, and authors have to pay the bills as well. Commercial activity is not universally incompatible with good scholarship. But when making money becomes the primary goal, scholarship evolves into something else.

Use your good judgement, and don't be frightened by all the detailed discussions above. A few good rules of thumb: Do your footnotes or references consist solely of http://www addresses, especially those involving ".com"? If so, you probably don't have many scholarly sources. Did you find a book on your own in a University library? It's more likely to be a scholarly source than if you found it after receiving an aggressive, hard-sell email solicitation from a commercial "content provider."

*

Los Angeles, February 2008 (Elvin Wyly)

"What I want to see is that you are fully engaged with an issue, and that you've broken some sweat trying to figure out the problem in all of its wonderful complexity." Barack Obama (1994). Current Issues in Racism and the Law. Syllabus and Reading Packet #1. Chicago: School of Law, University of Chicago, Spring Term. Excerpted in the New York Times and published at http://www.nytimes.com, August 2, 2008.

"In recent times numerous authors and publishers have come to suppose that readers are offended by footnotes. I have no desire to offend or even in the slightest way to discourage any solvent consumer, but I regard this supposition as silly. No literate person can possibly be disturbed by a little small type at the bottom of a page, and everyone, professional and lay reader alike, needs to know on occasion the credentials of a fact. Footnotes also provide an exceedingly good index of the care with which a subject has been researched." John Kenneth Galbraith (1954). The Great Crash 1929. New York: Time Books, p. 1.

"What on earth are our underpaid teachers, laboring in the vineyards of education, supposed to tell students about the following sentence, committed by the serial syntax-killer from Wasilla High and gleaned by my colleague Maureen Dowd for preservation for those who ask, 'How was it she talked?'

'My concern has been the atrocities there in Darfur and the relevance to me with that issue as we spoke about Africa and some of the countries there that were kind of the people succumbing to the dictators and the corruption of some collapsed governments on the continent, the relevance was Alaska's investment in Darfur with some of our permanent fund dollars.'

And, she concluded, 'never, ever did I talk about, well, gee, is it a country or a continent, I just don't know about this issue.'

It is admittedly a rare gift to produce a paragraph in which whole clumps of words could be removed without noticeably affecting the sense, if any.

...

Could the willingness to crown one who seems to have no first language have anything to do with the oft-lamented fact that we seem to be alone among nations in having made the word 'intellectual' an insult? (And yet...and yet...we did elect Obama. Surely not despite his brains.)"

The entire quote is from Dick Cavett (2008). "The Wild Wordsmith of Wasilla." New York Times, Talk Show blog, 14 November.

Safire's Fumblerules

Back in the late 1970s, William Safire issued an open call for "perverse" rules of grammar, "along the lines of 'Remember to never split an infinitive,' and 'The passive voice should never be used.'" He got an enthusiastic response, and he used readers' frustrations with all that they had struggled to learn from grammar school to create a set of useful and hilarious guidelines. It produced one of his most widely-cited essays: William Safire (1979). "On Language: The Fumblerules of Grammar." New York Times Magazine, November 4, p. SM4.

By the time he wrote that column, Safire had already become one of the most influential figures in the politics and everyday use of the English language in Washington, DC. Safire made his way into journalism and politics in the mid-1950s, and achieved fame and notoriety as part of a speechwriting team in President Richard Nixon's administration. In 1970 he coined the famous lines that Vice President Spiro T. Agnew used to dismiss critics of Nixon's Vietnam policies: the "nattering nabobs of negativism" and the "hopeless, hysterical hypochondriacs of history." Safire defended Nixon when the Watergate scandal broke, but soon became disenchanted as the scale of corruption and intimidation became apparent (and when Safire realized that he was one of those secretly taped by Nixon). Safire went on to write a twice-weekly essay for the Op-Ed Page of the New York Times from 1973-2005, in addition to his "On Language" column, which ran from 1979 all the way to 2009, only a few months before he died from pancreatic cancer in late September at age 79. (Read the rules, and then take note of the shadows in this valley after Safire's departure.) Robert D. McFadden (2009). "William Safire, Political Columnist and Oracle of Language, Dies at 79." New York Times, September 27, B8.

Safire's populist libertarian conservatism was a curious blend, and its history now looks quite charming and intelligent from the vantage point of the anti-intellectual, Rush-Limbaugh dittohead conservative thuggery that prevails across so much of America today. Safire certainly had plenty of ideological fervor when he went after his opponents; but above all he prized logic, consistency, and the crafts of argument, analysis, and writing. His "fumblerules" was a tiny part of the body of work he produced, but it is understandably one of the most widely remembered. We've all been guilty of violating many of the rules, but at least we can laugh when we proof-read. Personally, I would not banish the negative form and its subtle ambiguity. And starting a sentence with a conjunction gets the reader's attention precisely because of its violation of rules. I've also been entranced with the playful possibilities of alliteration, and I've never missed an opportunity to pass on the joke told to me by Phil Porter in the early 1990s: It is not known by whom the passive voice was invented. Still, Safire's advice is valuable: rules may be made to be broken, but only after they're clearly understood.

So, read Safire's fumblerules, and keep them in mind as you write, proofread, and rewrite.

The original citation for Safire's collection is:

William Safire (1979). "On Language: The Fumblerules of Grammar." New York Times Magazine, November 4, p. SM4.

Plagiarism Pitfalls, Norwegian Edition

September, 2010

[Contributed by Graeme Wynn]

"Colleagues:

Some years ago I collaborated in the production of a booklet, "Plagiarism and How to Avoid It," which we sold to students for 50c (and which at one time was top of the UBC Bookstore best seller list!). This booklet was later updated and made available free of charge on the web by Neil Guppy. Some folks are still using one or other of the above items to inform their students of potential "pitfalls"

But if you are concerned that even a "fifty cent pamphlet" fails to address the problem of plagiarism these days, you might take five minutes to show the video below to your classes. Although the message is the same as in those earlier works, this is undoubtedly a livelier rendition -- and there is no suggestion of plagiarism from the earlier works.

Make sure the cc caption below the video frame is turned on to get the subtitles."

Stian Hafstad et al. (2010). "En Plagieringsfortelling." Search & Write course. Bergen, Norway: Bergen University College, The Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration, and the University of Bergen.

Editing Exposed

The naked typo

Julia Johnson (2010). "Investor's Bold Plays Save Company." National Post, December 27, p. FP1, FP6. Reisa Schwartzman described the challenges she faced in saving a game company in which she had made an investment. As the firm slipped into bankruptcy, she refused to give up on her investment, and so she jumped in to try to turn around the enterprise herself. "Griddly Headz games have received 18 industry awards and seals. Recognition involves sending the game to an industry association to be reviewed and hoping for the best. 'You take the risk and you pay a fee and you send your game in to, for example, iParenting or National Parenting or the Teacher's choice award ... and basically you stand their naked,' said Ms. Schwartzman...."

Dude...

"Reality TV star Sarah Palin gave birth to a new word this year when she repeatedly tweeted 'refudiate' -- thus staking out unexplored lexicographic territory somewhere between 'repudiate' and 'refute.' Jumping to her own defense, because no one else was about to, Palin refudiated her critics on an episode of Sarah Palin's Alaska, in which she told her deeply disinterested-looking husband, Todd:

'Oh, geez! Yesterday I twittered the word 'refudiate' instead of 'repudiate' -- I pressed an 'f' instead of a 'd' and people freaked out about it.'

So back off, Snooty Liberal Intellectual Elite. Sarah didn't mean to write 'refudiate' -- she meant to write 'redudiate' -- which, of course, means to reacquaint oneself with The Big Lebowski."

Pete McMartin (2011). "Frivolous News of 2010: Please Read Before Vomiting." Vancouver Sun, January 1, A3.

Prove him wrong. Please, please prove him wrong.

Mark Baurlein, a Professor of English at Emory University, offers this assessment of contemporary student research methods (Bauerlein, 2011):

"When students take on research tasks, here is what they don't do:

- Visit the library and browse the stacks.

- Find an archive and examine primary documents.

- Read widely in the subject before identifying a topic.

Instead, they

- Type a term into Google.

- Consult Wikipedia's entry on the subject.

- Download six web pages, and cut and paste passages.

- Summarize the citations and sprinkle commentary of their own.

- Print it up and hand it in."

For Bauerline, the disciplined habits of mind traditionally associated with the research paper -- curiosity, reflection, critical judgment -- are at risk thanks to the false promises of universal digital availability of information. Information can be consumed and collected in a passive mode, without the hard work of organization, synthesis, and critical thought. But information isn't learning, and it isn't research. Thus the perils of all the digital tools, which "offer too many shortcuts, conveniences, and well-digested materials" that distract students from the serious work of active, engaged inquiry. "Teachers demand better usages ('Don't just rely on Wikipedia!')," Bauerline laments, "but they're up against 19-year olds who love speed and effortlessness. Good luck."

CopyLeft 2019 Elvin K. Wyly

Except where otherwise noted, this site is

Reading Liam McGuire's draft MA thesis on the Ten Cities of Toronto

May, 2012

The quickest way to tell a reader that you're lazy is to use Wikipedia as your main source...

The Reality of a Virtual Echo

I first began the scribbles that became this "guidelines" page quite a few years ago. One of the first items I wrote down, however, was "Write for an audience of humans, not computers." Even then, back in the dark ages of 2003 or 2004, it was clear that we primitive human beings were outsourcing more and more of the essentially human craft of writing to various devices and algorithms that were getting ever faster, ever more powerful. It felt deeply disorienting to see the craft of writing destroyed by the tyranny of code. More and more paper submissions showed telltale signs that the composition involved fewer decisions by a real, living human being -- with more pervasive, automated decisions reflecting the constructions of various software tools and corporate information empires.

For several years I felt like an increasingly retrograde, technologically incompetent throwback -- even more de-skilled than the original Luddites themselves (I can't weave). Then I discovered a new strain of technological humanism in Jaron Lanier, who is widely described as a "Silicon Valley pioneer" and "the father of Virtual Reality." Here's an excerpt from Lanier's book, You Are Not a Gadget, that clarifies why you should write for an audience of humans, not computers:

"It's early in the twenty-first century, and that means that these words will mostly be read by nonpersons -- automatons or numb mobs composed of people who are no longer acting as individuals. The words will be minced into atomized search-engine keywords within industrial cloud computing facilities located in remote, often secret locations around the world. They will be copied millions of times by algorithms designed to send an advertisement to some person somewhere who happens to resonate with some fragment of what I say. They will be scanned, rehashed, and misrepresented by crowds of quick and sloppy readers into wikis and automatically aggregated wireless text message streams.

Reactions will repeatedly degenerate into mindless chains of anonymous insults and inarticulate controversies. Algorithms will find correlations between those who read my words and their purchases, their romantic adventures, their debts, and, soon, their genes. ...

The vast fanning out of the fates of these words will take place almost entirely in the lifeless world of pure information. Real human eyes will read these words in only a tiny minority of cases.

And yet it is you, the person, the rarity among my readers, I hope to reach.

The words in this book are written for people, not computers."

Jaron Lanier (2010). You Are Not A Gadget: A Manifesto. New York: Knopf, p. ix.

Advice on Planning and Deadlines

from a former student...

"To the future students of the notable Elvin Wyly. Hi there, my name is [anonymized] and I am a former student of your current prof Elvin Wyly. The reason why Elvin has gotten me to write this message for all of you today is because of an ENORMOUS mistake which I made in his Geo 350 course last semester. As you may now know Elvin is an awesome prof who really cares about both his research and his students. I emphasize how awesome he is simply because of his willingness to provide US the students with not one but TWO days throughout the semester to submit to him the term project. I'm not sure who I'm speaking to right now but this message is written specifically for those students who, like me, are (or were) extreme procrastinators. As I said Elvin was nice enough to provide me and the rest of the 350 class with two varying dates to submit the term project. This in itself is extremely generous as with these varying submissions he provides you with a grade and feedback regarding the assignment (something I wouldn't know much about). Rather then taking Elvin up on his kind offer and submitting my assignments on at least one of the dates I decided I was going to be a smart guy and wait until the end of the semester to hand it in. At this point you may wonder, why is he still going of about this. The reason is because waiting to the end of the semester was THE SINGLE WORST IDEA EVER !! I'm sure all of you know how stressful things get at the end of the semester, something I apparently forget to mention to myself while procrastinating. Well just like many of you, I decided to procrastinate and wait until the end of the semester to "finish" everything. THIS DOES NOT WORK !!! With all the many assignments, papers, work, and everything else going on in my life, I kept putting off the assignment until, the next thing I knew, the Final Exam was the next morning. Needless to say I was unable to finish the project on time. Much to my relief Elvin, being the great guy his is gave me an early Christmas gift and gave me some extra time to finish. What is the point of this letter. Not to tell you to wait until the last minute and ask Elvin to present you with yet another gift. No, the point of this message is DO NOT PROCRASTINATE!!! It will bite you in the butt and you will be kicking yourself for not taking Elvin up on his many previous project submission date offers. So I depart by saying, do the assignment, start it early, and SUBMIT it during one of the first submission dates. Please don't wait until the end of the semester, believe me you will regret it. Thank-you."

[Verbatim quote, except for the anonymization, sent December 11, 2012]

If English is not your first language...

...this does not necessarily mean that your mark will suffer. The advice and recommendations on this "guidelines" page certainly do emphasize that you work to the best of your ability to pay close attention to the craft of writing. But all papers are marked on a multi-dimensional set of criteria. This means that any shortfalls in your English language skills can be counterbalanced by excellence in the quality of your analysis of evidence, your deployment of logic in constructing arguments, and your creativity in conceptualizing patterns and processes. In other words, content matters, and so does hard work. I can tell the difference between a lazy native-English speaker who has dashed together an essay with lightning-fast cut-and-paste skills, versus a hard-working student laboring to communicate rigorous scholarship across the extraordinary challenges of humanity's linguistic kaleidascope.

Here's a specific example. During a course several years ago, Kexin Chen came to visit my office hours. At first she was under the impression that my course required all students to write their term papers about the City of Vancouver. (Why would I impose such a silly requirement? Vancouver is interesting, but not that interesting!) Once we got past that misunderstanding, we had a wonderful discussion about many things urban, including the dynamics of urban growth, politics, and landscape change in a city that she knew well: Chongqing, P.R.C. At one point Kexin asked a question that reminded me of a book chapter I had read years earlier. I grabbed the book off the shelf, handed it to her, and said, "maybe some of these ideas will help you tell an interesting story about your hometown."

Kexin borrowed that book -- Meinig and Jackson's delightful The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays -- and wrote a fascinating and rigorous paper. The language does make it difficult for a native-English speaker to read and understand every aspect of the argument; but the depth of engagement with theoretical and empirical material is quite remarkable. The paper thus earned a very high mark.

Kexin Chen (2012). Chongqing: A City Under the Red Veil. Vancouver, BC: Urban Studies Program, Department of Geography, University of British Columbia.

[Posted with kind permission of Kexin Chen.]

"I asked Mr. French to supply a couple of his clients to talk to me, and at press time he was still trying to find some. 'They're afraid,' he said. 'They know that admitting they had paid help -- well, one client said to me that dealing with the Wikipedians is like walking into a mental hospital: the floors are carpeted, the walls are nicely padded, but you know there's a pretty good chance that at any given moment one of the inmates will pick up a knife.'" -- Michael French, the Chief Executive of Wiki-PR, a firm specializing in creating and managing Wikipedia pages for paying customers seeking to shape their online reputations behind the illusion of Wikipedia's perceived populist, grassroots community. Quoted in Judith Newman (2014). "Wikipedia-Mania." New York Times, January 9, p. E1, E2, quote from p. E2.

News Flash: According to Murdoch University Dubai, All Student Plagiarism is Committed by Brown Kids, while All the Enforcers are White People. WTF?

why

cheat?

Editing by Ear

The best way to edit your writing is to find a quiet space in which you can gently read out loud the words you've written, concentrating on the interplay between the visual appearance of the written sentence and the sound of oral communication. You'll quickly improve the clarity, flow, and organization of your writing -- and you may also prevent major misinterpretations. Consider the comma, for example -- a symbol devised by a printer working in Venice circa 1500. The comma is intended to prevent confusion by separating words and phrases, and it tells the reader when to pause between different concepts or ideas. One of the more important uses is called the "serial comma," which appears in lists of three or more things. Things can get a bit amusing if you forget the serial comma:

"We invited the strippers, J.F.K. and Stalin."

"This book is dedicated to my parents, Ayn Rand and God."

"And there was the country-and-Western singer who was joined onstage by his two ex-wives, Kris Kristofferson and Waylon Jennings."

If you edit by ear, you'll realize that each of these sentences requires just one more comma to make things clear.

Source: Mary Norris (2015). "Holy Writ: Learning to Love the House Style." The New Yorker, February 23 & March 2, pp. 78-90, quotes from p. 84.

The Guidelines Explained

Read the letter, and then watch a video of my reaction to the response.

On the left side,

Assorted Quotes, Recommendations, Illustrations, and Reflections on Writing, Plagiarism, and other matters

|

On the right side,

Detailed Explanations for the Seven Simple Guidelines

|

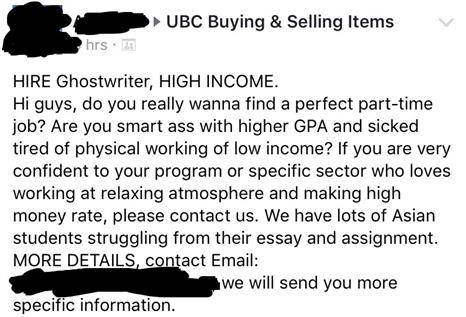

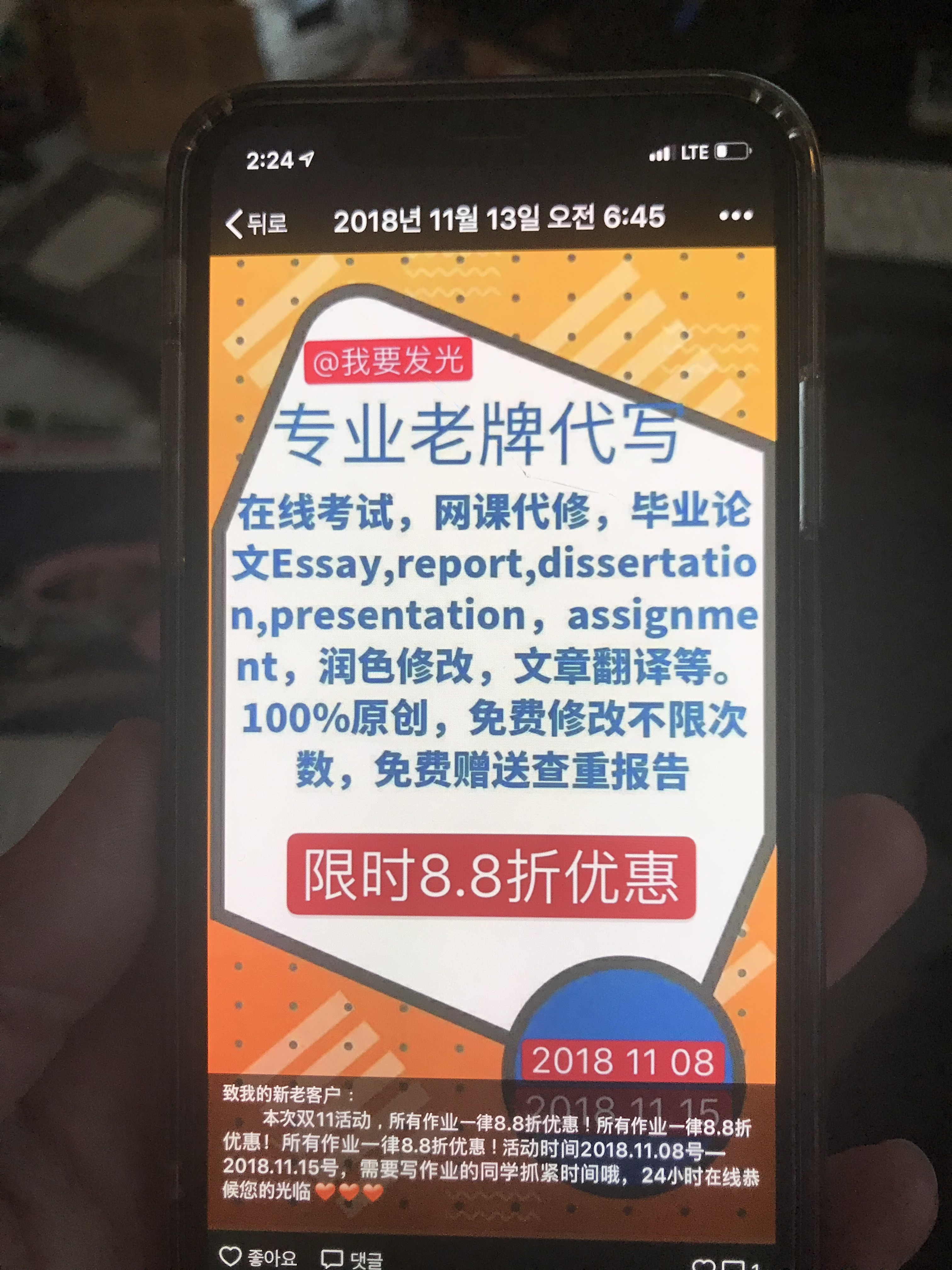

This is why Guideline # 1 is mandatory. There's an entire industry devoted to finding profit in academic anxiety, and pressuring even the most honest of students to pay money to take shortcuts and find an easy path to a good grade. Just as we've seen remarkable innovations in how global capitalism has found ways to profit from racism, here we see predatory cheating entrepreneurs explicitly racializing their smart ass discourse: let me assure you that there is no correlation whatsoever between 'Asianness' and 1) success/failure or 2) honesty/dishonesty. [Source: from an anonymized and redacted advertisement recently posted to the UBC section of Reddit.]

"'Are you aware that significant portions of this document that you passed to three committee chairmen to meet a public law were plagiarized from Wikipedia?' he asked Work. 'No, I did not know that the information in that document came from Wikipedia,' Work replied." --From an exchange between Devin Nunes and Deputy Defense Secretary Bob Work, regarding a required report to the House Intelligence, Armed Services, and Defense Appropriations Committees regarding the optimal location for a Joint Intelligence Center with the United Kingdom. Work defended his compliance with the technical requirements of the National Defense Authorization Act on making the determination of the center location, despite the questionable lineage of the information cited as background for that decision. 'I'm just alarmed, Secretary Work, that we would rely on Wikipedia, a free online encyclopedia famously known for most high school students plagiarizing their homework. And that the Department of Defense would even use Wikipedia, a free online service to provide any information to Congress put in any report," said Nunes. All quotes from Kristina Wong (2016). "Intel Chairman: Pentagon Plagiarized Wikipedia in Report to Congress." The Hill, November 17.

Make America Steal Again

The "decision to recall the book comes after a report by CNN that Ms. Crowley, a conservative columnist and TV personality who was chosen by President-elect Donald J. Trump for a high-ranking communications role at the National Security Council, had included plagiarized passages from Wikipedia and newspaper articles. ... More examples of plagiarism surfaced in Ms. Crowley’s Ph.D. dissertation, according to Politico, which found more than a dozen examples of passages that had been lifted from scholarly works."

From a story describing a publisher's decision to withdraw the digital edition of Monica Crowley's 2012 book What the Bleep Just Happened? Trump's transition team, perhaps predictably, immediately declared that the charges of plagiarism were just "a politically motivated attack." Politically motivated attacks, however, are precisely Crowley's genre. Her 2012 book is a nasty attack on Obama's re-election. Crowley first became famous working as an assistant for the disgraced former president Richard Nixon; while she worked for him she secretly kept a detailed diary of all her private conversations with him, using this private information as the basis for a book published after Nixon's death in 1994.

All quotes from Alexandra Alter (2017). "HarperCollins Pulls Book by a Trump Pick after Plagiarism Report." New York Times, January 10.

*

Crowley has, apparently, earned an entire Doctorate in Plagiarism:

Crowley's Ph.D. Dissertation, Clearer Than Truth: Determining and Preserving Grand Strategy: The Evolution of American Policy Toward the People’s Republic of China Under Truman and Nixon, submitted for a degree in International Relations from Columbia University, contains multiple instances of plagiarism, according to an investigation by Politico Magazine. From their investigation: "By checking passages in the document against the sources Crowley cites, focusing on paragraphs that come before and after footnotes of key sources in her bibliography, we found numerous structural and syntactic similarities. She lifted passages from her footnoted texts, occasionally making slight wording changes but rarely using quotation marks. Sometimes she didn’t footnote at all. Parts of Crowley's dissertation appear to violate Columbia's definition of 'Unintentional Plagiarism' for 'failure to 'quote or block quote author's exact words, even if documented' or 'failure to paraphrase in your own words, even if documented.' In other cases, her writing appears to violate types I and II of Columbia's definition of 'Intentional Plagiarism,' which are, respectively, 'direct copy and paste' and 'small modification by word switch,' 'without quotation or reference to the source.'"

See Alex Caton and Grace Watkins (2017). "Trump Pick Monica Crowley Plagiarized Parts of Her Ph.D. Dissertation." Politico Magazine, January 9, 2017

"It fucked me up mentally and it still makes me feel useless because I was still allowed to pass the course, even though I had committed a serious offence, no matter the circumstances."

From an anonymous confession of plagiarism by a student in Computer Science at UBC. Read the full discussion here. Anonymous, but see the very end, when a commenter writes, "Hey I remember you!"

Yet More Frontiers of Cheating in the Place of Mind

From a discussion thread on reddit.com/r/UBC, February 2017 (left), from a widely-circulated ad for discounts on custom-written cheating materials, December 2018 (below).

Planetary Frontiers of Competitive Cheating

"The journal Tumour Biology revealed last month it had retracted 107 studies, discovering the authors — all of whom seem to be from China — had suggested peer reviewers for their work, provided the journal false emails for those people, and then sent back positive reviews they had actually written themselves." Tom Blackwell (2017). "Science’s quality-control system under attack, with push to publish research before it’s peer-reviewed." National Post, May 24.

The Plagiarized Infinite Loops of Cybernetic Cognitive Capitalism

Let me explain the terms in this title. If you're reading this page, you already know how to define and identify 'plagiarism.' An infinite loop is a computer-science term for a section of code that leads a program to keep repeating itself, endlessly going in circles. It's a common source of problems that lead programs to 'freeze' or 'crash.' Cybernetics is a science that was first proposed in the 1940s by a brilliant mathematician Norbert Wiener; he borrowed a term from ancient Greek -- kubernetes, a "steersman," -- to develop a theory of the use of messages and feedback mechanisms in systems that relied on both machines and humans working together to achieve a set of goals. Today, cybernetics is a popular term to describe a world of ubiquitous smartphones and 4GLTE wi-fi internet connectivity ("Fourth-Generation, Long-Term Evolution"). Finally, "cognitive capitalism." This is a phrase introduced several years ago by social theorists studying the effects of decades of deindustrialization alongside breakthroughs in automation that seemed to be fundamentally changing the rules of the game in capitalist competition. It's also been adopted as a catchy slogan by giant corporations, like IBM's current ad campaign, "Welcome to the Cognitive Era." Innovation in the making of things is becoming less and less important; more and more economic activity is focused on "cognitive" services: constantly re-designing goods and services to satisfy fast-changing consumer preferences; crafting sophisticated marketing and advertising systems in order to persuade consumers to make the right choice in an information-overload world flooded with commodities; pursuing wealth through the creation of cultural products (cinema, theatre, music, YouTube videos) defined by image and perception; and managing the resulting consequences of celebrity for those who have become famous, and for those who want to be famous. Do you have a press agent? A tour manager? A lawyer to protect your name, your image, your patents and trademarks, your intellectual property?

All of that is "cognitive capitalism." As more and more social lives move online into social media ecosystems where every page view, every Facebook 'like,' is recorded, tracked, and correlated with the billions of other datapoints created by the strange 'cyborg' blends of humans and algorithmic robots (a shockingly high share of Twitter traffic is generated by what are called 'social bots').

Now we can begin to make sense of that title. As cognitive capitalism creates new informational possibilities, it creates endless new opportunities for various kinds of deception and fraud -- which in turn create the need for new kinds of surveillance and policing mechanisms. One of those mechanisms involves the deployment of advanced computer-science innovations in artificial intelligence and pattern recognition to scan student papers for similarities, to detect possible cases of plagiarism. As more students come to know and understand how their words are scanned by surveillant computer code -- what I have come to call the 'academic Robocop,' the 'cognitive predator drone' -- it changes the meanings and societal contexts in which they write. Indeed, I would go so far as to suggest that it fundamentally changes the very nature of writing and scholarly knowledge production. It also unleashes a sort of surveillant arms race: one local company promises, for a price, to use its own software system to pre-scan papers written through custom-designed fraud and deception -- to ensure that the cheating will not be detected by UBC's plagiarism-detection system. We begin to see an infinite loop of intensified competition and information overload, pressures to save time through the ubiquitous liquid postmodernity of cut-and-paste culture, and incessantly innovative systems to measure and monitor the work produced by students. The entire system expands with the erosion of trust, and creates its own burgeoning market demand by reinforcing widespread cynical assumptions of deceptive, competitive behavior.

And what happens when this entire regime is turned towards the source of the next-generation innovations of that surveillance code -- the students who are now learning the computer-science coding techniques that will chart the latest frontier-zone pioneer fringes between artificial intelligence and natural stupidity?

For a glimpse of some of this future, see a recent update on plagiarism controversies in computer science classes at Harvard and other elite universities:

Jess Bidgood and Jeremy B. Merrill (2017). "As Computer Coding Classes Swell, So Does Cheating." New York Times, May 29.

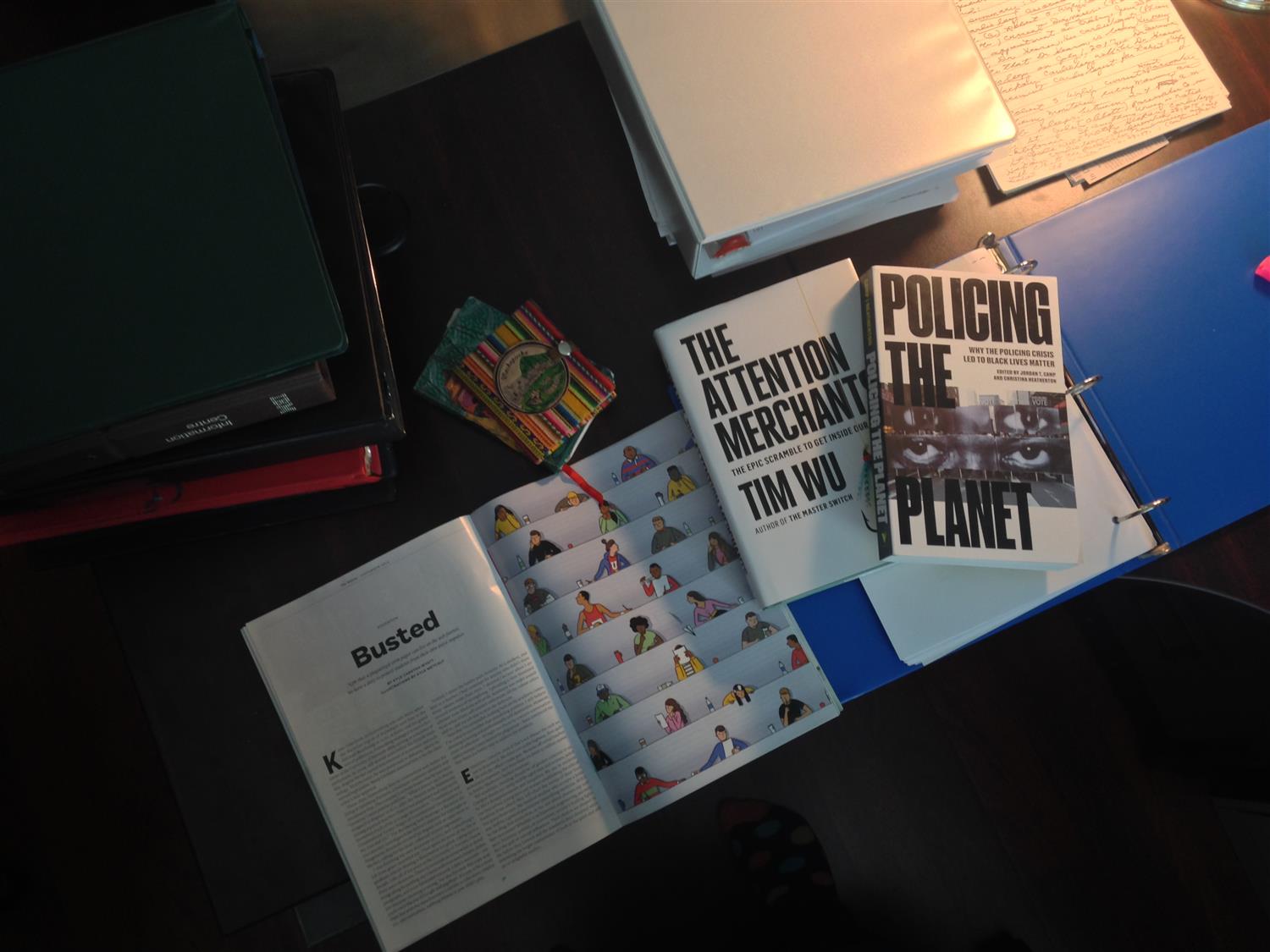

Busted!

Cheating, Copyright, and Coercion

I'm enjoying the Vancouver summer sun, preparing for the joyous crowds of September, and catching up on reading, working my way slowly through the huge stacks of books, newspapers, and magazines packed into this tiny home office. So many books, so little time! And then of course there is that massive planetary nervous system, what the Silicon Valley visionaries are theorizing as the "Global Brain" of the internet. Lots to read there too. And more of that reading material becomes ever more frightening, given the intensification of high-stakes competition, the scramble to make money in a world where everyone is trying to outrun the bots, and the seemingly infinite contradictions of law and public policy. Hours spent reading the hundred-plus-page opinion issued by the Federal Court of Canada in Access Copyright v. York (Phelan, 2017), still leaves it unclear what kind of "fair dealing" is allowed for educational purposes in teaching. The only thing that's clearly encouraged is to coerce students to pay as much as possible for "intellectual property." It seems that Canadian jurisprudence is slowly building the infrastructures of surveillance and fear that will destroy academic freedom - fulfilling the dreams of an undergraduate student who recently spent forty-five minutes in my office, debating the fatal flaws of that concept he found so abhorrent: academic freedom? What's that?

He had come to office hours to ask what all the fuss was about, after he saw that phrase in the press coverage and social media discussion of a scandal that raged on the UBC campus in the fall of 2015. The Chair of UBC's Board of Governors had not-so-subtly pressured Jennifer Berdahl, Professor of Leadership Studies, Gender, and Diversity in the Sauder School of Business. Berdahl had written a blog post offering a set of hypotheses on the role of race and gender in the "white masculinity contest" that so often defines powerful institutions. Perhaps, Berdahl suggested, it had been President Arvind Gupta's failure to win that contest that explained why he had suddenly been fired by the Board of Governors less than halfway into a five-year term. With no explanation provided by the Board of Governors, Berdahl's theory quickly got a lot of attention. The BOG Chair called Berdahl, and after the requisite platitudes - I'm not trying to interfere with your academic freedom, blah, blah, blah - that's exactly what he attempted to do. Harming the reputation of the institution undermines what we're trying to do, he tried to convince her.

The irony is that this is exactly what that student in my office wanted to see: an orderly, organized institution, working at optimal efficiency, with no dissent. Academic freedom: what's that? he asked. Once he was presented with the thirty-second version of John Dewey, the AAUP, and the 1940 Statement of Principles of Academic Freedom and Tenure, he thought that this was the worst idea in the world. Academic freedom is dangerous, he emphasized. You can't allow professors to decide what to teach, or how to teach, he declared. They have to do their jobs. They have to be told what to do, and then they have to do it. This was one of my best students. He wasn't just reacting with a casual, cynical dismissal of the concept. He had a full-fledged political philosophy on how the institutions of knowledge production should function in contemporary society. He had given this a lot of thought. Academic freedom is dangerous. It is disorganized and inefficient. We slid into a lengthy discussion that became a serious debate - a friendly, respectful debate - as my subconscious marvelled at the scenario. Elvin is discussing the finer points of law and regulation with a third-year undergraduate student, I thought, and he's got the skills, expertise, and articulate passion of a senior lawyer, or a high-profile CEO or government official. We talked for forty-five minutes.

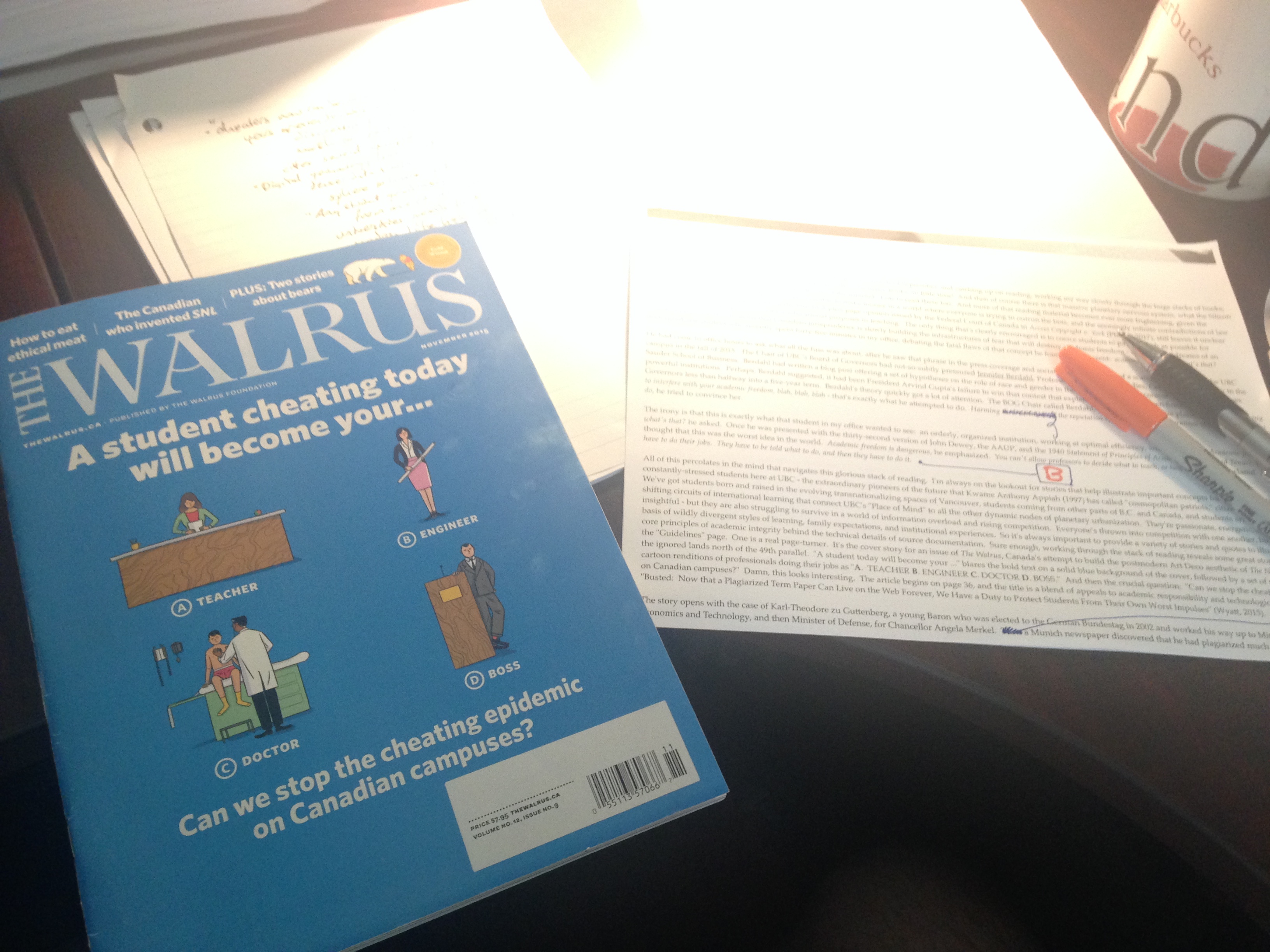

All of this percolates in the mind that navigates this glorious stack of reading. I'm always on the lookout for stories that help illustrate important concepts for the brilliant-but-constantly-stressed students here at UBC - the extraordinary pioneers of the future that Kwame Anthony Appiah (1997) has called "cosmopolitan patriots," citizens of the world. We've got students born and raised in the evolving transnationalizing spaces of Vancouver. We have students coming from other parts of B.C. and Canada, and we also have students arriving from the shifting circuits of international learning that connect UBC's "Place of Mind" to all the other dynamic nodes of planetary urbanization. They're passionate, energetic, and insightful - but they are also struggling to survive in a world of information overload and rising competition. Everyone's thrown into competition with one another, but on the basis of wildly divergent styles of learning, individual and family expectations, and institutional experiences. So it's always important to provide a variety of stories and quotes to illustrate the core principles of academic integrity behind the technical details of source documentation. Sure enough, working through the stack of reading reveals some great stories to add to the "Guidelines" page. One is a real page-turner. It's the cover story for an issue of The Walrus, Canada's attempt to build the postmodern Art Deco aesthetic of The New Yorker for the ignored lands north of the 49th parallel. "A student today will become your ..." blares the bold text on a solid blue background of the cover, followed by a set of straight-realist cartoon renditions of professionals doing their jobs as "A. TEACHER B. ENGINEER C. DOCTOR D. BOSS." And then the crucial question: "Can we stop the cheating epidemic on Canadian campuses?" Damn, this looks interesting. The article begins on page 36, and the title is a blend of appeals to academic responsibility and technological warning: "Busted: Now that a Plagiarized Term Paper Can Live on the Web Forever, We Have a Duty to Protect Students From Their Own Worst Impulses" (Wyatt, 2015).

The story opens with the case of Karl-Theodore zu Guttenberg, a young Baron who was elected to the German Bundestag in 2002 and worked his way up to Minister of Economics and Technology, and then Minister of Defense, for Chancellor Angela Merkel. Then, about a decade into this high-profile political career, a Munich newspaper discovered that he had plagiarized much of his Doctoral dissertation on US-EU Constitutional development. Guttenberg had to resign in disgrace. His doctoral degree was revoked. A district attorney launched an investigation of Guttenberg for copyright infringement. And then the author of this Walrus essay, Kyle Carsten Wyatt, begins to explain why he found this case of the plagiarizer who came to be known as "Baron zu Googleberg," so interesting:

"I was finishing my own doctorate in 2011, and Guttenberg's fall from grace unsettled me. I had spent six years of my life in graduate school. Writing a dissertation is a grind, taking up to a decade. Like all of my peers at the University of Toronto, I knew there were shortcuts. There is tremendous temptation to speed things along by padding one's thesis with borrowed phrases, stolen paragraphs, and even fabricated research. I didn't succumb not just because cheating is wrong, but also because this copy-and-paste era is the era of Google and gigaflops. It's easy to be a word thief, but with the data forensics available to educators, employers, and journalists, nabbing thieves is now child's play." (Wyatt, 2015, p. 36).

Wyatt relates his experiences trying to keep his classes honest when he taught literature at the University of Toronto. He tried being the "good cop," empathizing with students who face impossible schedules and infinite cut-and-paste temptations. He "played the eat-your-broccoli card," reminding students that you're only cheating yourself if you plagiarize someone else's book review rather than, for example, actually reading through that 700-page literary masterpiece assigned for the course. But Wyatt also played bad cop, with stern warnings:

"I introduced standard-issue threats into my syllabus: 'There is no excuse for plagiarism, paper purchase, or other forms of academic dishonesty. If I find any indication of such behavior, I will vigorously pursue the case with relevant University authorities.' I explained that there was no statute of limitations on cheating, and that I kept papers and correspondence for years. If a newshound ever came poking around, looking to dig up some dirt, the contents of my hard drive could become Exhibit A." (Wyatt, 2015, p. 38).

Wyatt tells several stories of catching students flagrantly lifting entire paragraphs from sources found on the internet - a violation instantly detected with a Google search - and then he situates today's circumstances within the longer history of competition and cheating. Plagiarism has its own historical traditions, from the strategic maneuvers and innovations designed to game the system of civil service exams used to allocate prestigious government jobs in imperial China, to the many cases of exam cheating in Canada in the twentieth century. Wyatt reminds us that the distinguished Conservative luminary and publishing magnate Conrad Black was expelled from Upper Canada College in 1959 for the infraction of selling examinations. And as the mid-twentieth century Cold War revolutionized society with dramatic technological advances, a parallel arms race involved new technologies used by cheaters trying to outflank the technological surveillance deployed by educational institutions trying to detect academic dishonesty. Wyatt's analysis is meticulously researched, with a delightfully engaging writing style that moves creatively and convincingly between the present and the past. Today's Cold War cheating arms race is mediated by a world of ubiquitous information, and as the Guttenberg case demonstrates, "cheaters now can become disgraced years or even decades after their discretions, thanks to the march of technology" (Wyatt, 2015, p. 39). "Digital technology has created longer, denser data trails in every sphere of human activity," Wyatt (2015, p. 39) explains, and so "[a]ny student graduating from one of our colleges or universities needs to know that modern life has become a fishbowl" (Wyatt, 2015, pp. 39-41).

You will notice here that there are careful citations, quotations, and source documentation details to distinguish the work of Kyle Carsten Wyatt from the ideas expressed by the author responsible for assembling the textual fragments you're reading. We do not wish to be a word thief. Strangely enough, though, the digital fishbowl of modern life quickly revealed some fascinating aspects of the production of Wyatt's essay. "Busted" was posted on the Walrus website in October, 2015, and then distributed in the November, 2015 issue of the print magazine. That print copy is the version I found in this big stack of books, newspapers, and magazines in the cubbyhold office. But soon the essay on the Walrus website went "404" - "file not found" - after it was revealed that Kyle Carsten Wyatt was not really the author. Alex Gillis, a freelance writer and lecturer at Ryerson University, had pitched the story idea to the Walrus in March of 2015. Then he spent several months on research and writing. In late August, Gillis's first draft had been approved by the Walrus Managing Editor, Kyle Carsten Wyatt. But "when Gillis handed in his second draft two weeks later, he was given an ultimatum - either he keeps his byline but has the piece rewritten by The Walrus, or receives a 50 percent kill fee." (Chan, 2015).

"Kill fee?" Did you know that there was such a thing? I didn't.

Apparently, this is an increasingly common practice in the publishing world. It denotes the situation where a payment is negotiated for a freelancer when a publisher decides not to proceed with a project that had been previously assigned and agreed. It's apparently being used more frequently to increase the supply of good-well-researched prospects for final stories - while helping to avoid paying the full costs of the research and writing required to produce such good work. Many independent writers and journalists have been voicing objections to the practice in recent years.