Why a page for the simple, obvious, taken-for-granted skills of literacy? Well, why not? Isn't it our job to question every phenomenon that's presented as simple or obvious? Aren't we supposed to challenge anything that is taken for granted?

I also have other reasons, that are best understood if we consider a quote from Peter R. Gould, a mathematician who then became a leading force in Geography's Quantitative Revolution in the 1950s and 1960s. In his powerfully brilliant and deeply reflective book Becoming a Geographer, a collection of essays published the year he died in 1999, Gould examines the experience of teaching a course on the history and philosophy of geography. Their text was David Livingstone's The Geographical Tradition (Blackwell, 1992). Preparing for the course, Gould felt as if it would be fraudulent for him to stand up on his "hind legs," as he put it, and lecture to students from a text that they were perfectly capable of reading for themselves. The real learning, Gould felt, would be achieved by capping enrollment to ensure a class size that could allow everyone to get to know one another. In this seminar format, everyone reads the text, bringing to the encounter their own experience, knowledge, perspective, and priorities. And then the discussion begins, with evolving combinations of agreement, exploration, and debate. There's not really a search for agreement here -- consensus can often be the death of innovation in any discipline. Instead there is a patient blend of individual effort and collaborative conversation that helps everyone to find a path through the history and present of a domain of knowledge -- in this case, the history and theory of Geography -- what Livingstone brilliantly analyzes in his wide-ranging Geographical Tradition as an evolving, conversational process. "Tradition" here is an enigmatic and perhaps even deceptive term: it's not an appeal to a fixed set of conventions inherited from the past, but rather an exploration of how different generations of geographers over the decades and centuries, have offered wildly different answers to the question: What is "Geography"?

Well, that was the plan. But Peter Gould's vision for that seminar in the Spring of 1994 collided with a different kind of reality:

"Things did not turn out that way. A book that I had read easily and with great pleasure after thirty or more years as a professional geographer, and from which I learned many new things, and recalled many old things long forgotten, was tough and challenging work for most of the students, including those in their first year of graduate work. With rather lost and blank faces looking at me, I recalled Derek Gregory's comment some years ago, when he visited us at Penn State in our Distinguished Visitors Program, that 'The most difficult thing that we face at Cambridge is teaching people how to read,' something that I resonated to immediately, because I only really learnt to read myself at the age of forty-seven." (Gould, 1994, p. 256)

This hit me like a brick when I first read it. Gould (1994, p. 340) then provides a footnote. "Since I was not totally illiterate before 1980," he clarifies,

"this may seem a strange statement, but when you spend sixteen weeks reading forty-five pages of Martin Heidegger's "Anaximander Fragment" with a philosopher like Joseph Kockelmans you realize what reading means. Apart from technical and methodological matters, this was one of the few genuine intellectual challenges of my entire academic career."

Gould's reflection intersects with an arresting passage right at the end of Mortimer Adler's deceptively simple yet powerful manifesto, How to Read a Book. "There is a strange fact," Adler tells us, "about the human mind, a fact that differentiates the mind sharply from the body. ... there is no limit to the amount of growth and development the mind can sustain. The mind does not stop growing at any particular age." This is an extraordinary advantage, but it has risks. Without labor and challenge, our minds can atrophy. Adler cites the example of workers who die soon after they retire. "They were kept alive by the demands of their work upon their minds," Adler tells us; "They were propped up artificially, as it were, by external forces," and freedom from those external forces can be fatal. But now there's a new dynamic in the information society. "Television, radio, and all the sources of amusement and information that surround us in our daily lives are also artificial props," Adler warns. "They can give us the impression that our minds are active, because we are required to react to stimuli from outside. But the power of those external stimuli to keep us going is limited. They are like drugs. We grow used to them, and we continuously need more and more of them. Eventually, they have little or no effect. Then, if we lack resources within ourselves, we cease to grow intellectually, morally, and spiritually. And when we cease to grow, we die."

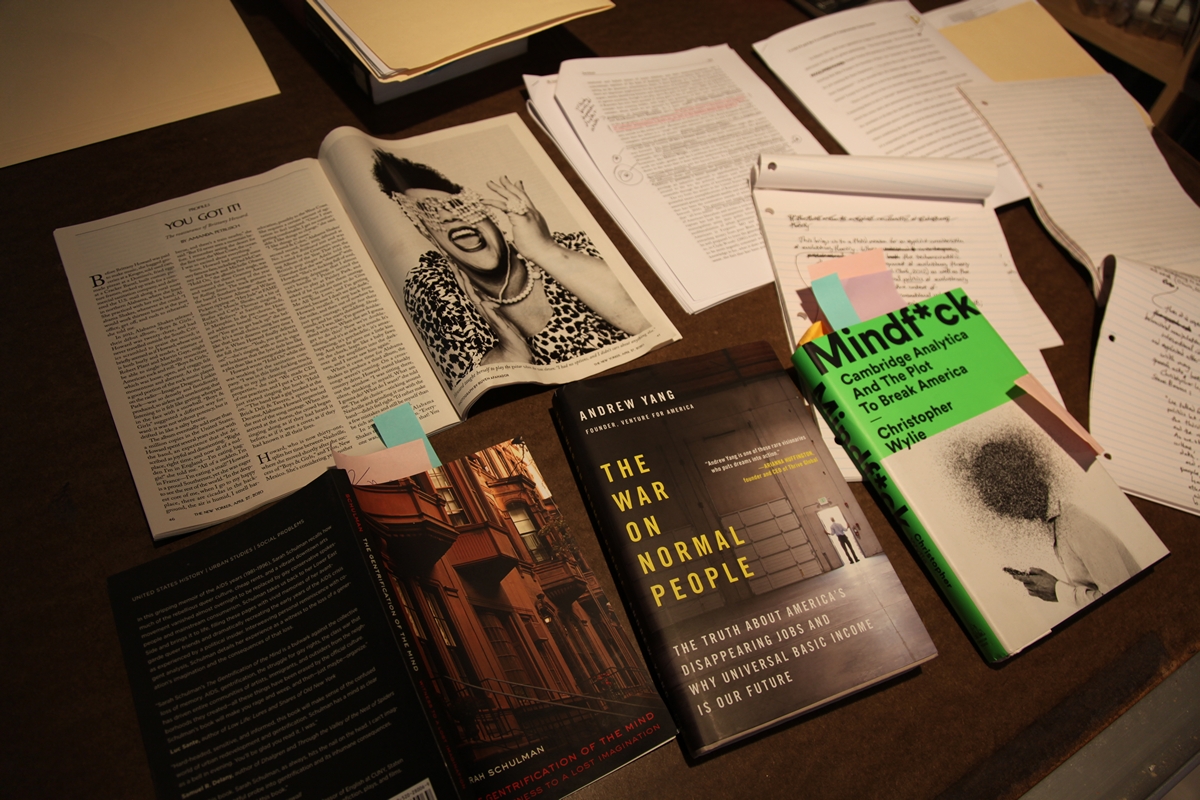

These words were written in 1940. But they help us understand the overwhelming apocalyptic beauty of our present moment, when we are overwhelmed with information, when each day it becomes ever more difficult to keep up with the firehose of emails, text messages, Twitter storms, Facebook newsfeeds, Instagram posts, bingeworthy Netflix marathons, and all the rest. In the eye of the informational hurricane, how do we find time and space for reading? My approach relies on sustaining the accumulated respect for the cultures of print and paper. I am inspired by Nicholson Bakerís book, Double Fold: Libraries and the Assault on Paper, which was published in the first year of our present century. Things have only gotten worse in the years since. Everything is forcing us to do everything online, in an evolving ecosystem that moves faster and faster. But speed is dangerous, and leads to what the linguist Naomi Baron (2015) calls ďreading on the prowl.Ē Print and paper, by contrast, slow us down. At slower speeds weíre able to reclaim the humanity of our own thoughts, at a more genuinely human scale that does not rely on the accelerating velocity of code in the networks of self-replicating algorithms. To really read something with care and respect, therefore, I prefer to have it in paper. Yes, it looks terribly unsustainable to have things in paper, but that's just an illusion: the accelerating product lifecycle of electronic devices in planetary commodity chains is far more dangerous than the circulation of recycled wood fibers in the use of paper as a renewable resource. So here is one small part of the archive of reading. Stacks of test essays and term papers from fall classes, from the next generation of brilliant, creative undergraduate students. Then a massive stack of various kinds of reading and service contributions from the last seven or eight months. Drafts of theses by Masters and Doctoral students. Drafts of articles and book manuscripts sent for review. Reference materials to be used in writing letters of recommendation. All sorts of other kinds of reading assignments that Iíve probably forgotten. But these are props, and their very materiality, the very reality of every wood fiber, is a reminder of the powerful, valuable demands placed upon the mind. Itís a reminder of how that mind can and must be changed, over and over again. And itís a reminder that there are limits. Perhaps it is time to let some of it go, to recycle.

References

Adler, Mortimer (1940). How to Read a Book. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Baron, Naomi (2015). Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gould, Peter (1994). "Perspectives and Sensibilities: Teaching as the Creation of Conditions of Possibility for Geographic Thinking." Journal of Geography in Higher Education 18, 177-189, reprinted in Peter R. Gould (1999). Becoming A Geographer. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 254-266, footnote on p. 340.

*